This year has seen plenty of campus speech controversies, but none made as much news as a leaked video showing members of a University of Oklahoma fraternity singing a racist song on a private party bus.

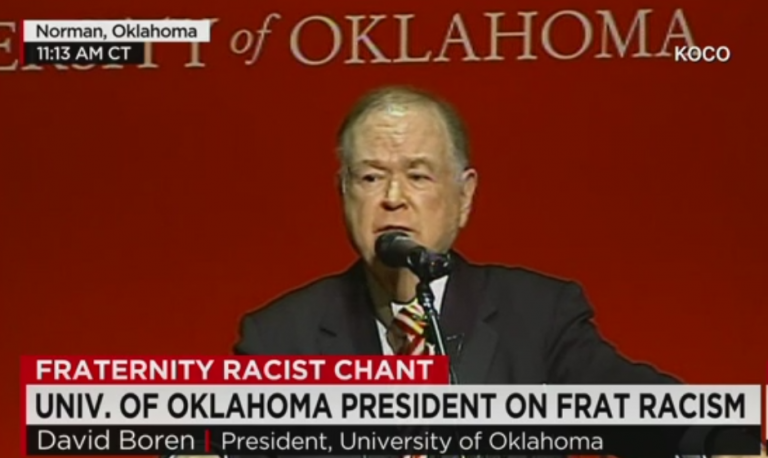

Many were horrified that college students would shout along to lyrics about lynching. But then University of Oklahoma president David Boren announced that two of the students had been expelled. That move, nearly everyone agreed, violated their constitutional rights.

Reconciling speech and equality rights can be a complicated business. The courts have struggled to develop guidelines that promote equality without undermining constitutional rights. For many years, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) offered institutions guidance in line with this approach, recognizing the need to protect expression of even controversial ideas and protect students from harassment when it “effectively bars the victim’s access to an educational opportunity or benefit.”

However, in October 2010 OCR expanded the idea of harassment to include “verbal acts and name-calling…that may be harmful or humiliating,” even though the Supreme Court has said that “mere utterance of an…epithet which engenders offensive feelings” is not harassment, but is protected speech.

The Court protects such speech — not to endorse it, but to preserve a right that is itself critical to the cause of equality. The civil rights movement and every social justice movement succeeded only because people were able to speak out and protest, even if they insulted and offended others in the process. To undermine this critical right is to put at risk the very equality goals anti-harassment regulations seek to enforce.

According to black students, the problems they face on campus — like poor retention and graduation rates and less financial aid — existed before the video surfaced. Perhaps there’s a problem at OU that goes beyond the reprehensible acts of some students on a party bus.

Which casts further doubt on Boren’s actions. By focusing on the students, he deflects attention from the university, and what it did or didn’t do to create a hostile educational environment, which will surely persist after the students and the fraternity involved in this situation are gone.

The Department of Education’s recent guidance on the issue of harassment has been not just muddled but counterproductive, compromising First Amendment rights while failing to ensure equality. Silencing a few boorish students isn’t the answer.