This article originally appeared in Censorship News 126

Museums, schools, and performance spaces have thus become battlegrounds where conflicts over race play out. Emblematic of these conflicts is the recent high-profile controversy at the Whitney Biennial in New York City, where protesters called for the removal and even destruction of a painting based on the photograph of Emmett Till lying disfigured in his casket. In arguments that are familiar and variously leveled at exhibitions, books, and art projects, critics questioned the moral right of a white artist, Dana Shutz, to use such a potent symbol of racial violence. They accused her of cultural appropriation, slammed her for exploitation and racial insensitivity, and generally condemned what they see as a white supremacist art world. Questions ranged from the right of a white artist to represent black historical trauma to the very capacity of white people to empathize with the black experience.

Debates about representing the history of racism extend to works in the American literary canon. The historically accurate use of racial slurs often disturbs contemporary sensibilities and creates tension in schools and communities. Last winter, for instance, a Virginia school district removed To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from its classrooms and libraries in response to a parent’s complaint about the books’ racist language. Shortly after, a school district in New Jersey considered redacting racial slurs from Ragtime, a Tony Award-winning musical based on E. L. Doctorow’s novel, set in Harlem in the early 1900s. NCAC reminded school officials that purging the production of the language would distort historical realities.

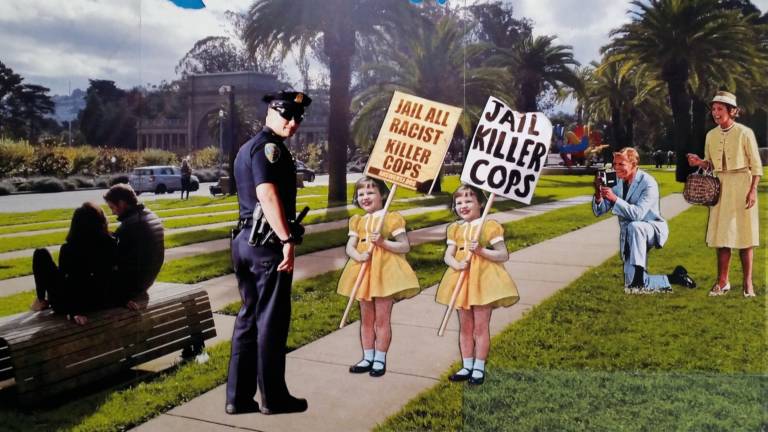

While debates rage over the moral right and ability of white artists and writers to deal with racially charged material, works by black artists alluding to police violence today, and racial violence historically, have met similarly heated opposition: in the nation’s Capitol, a high school student’s allegorical painting of a protest against police violence was taken down by Republican legislators, sparking a partisan battle and an ongoing legal case. In San Jose, California, a school district exhibition celebrating Black History Month that featured paintings of historical incidents of violence against black people was removed in response to complaints that it was too political. The censored African-American artist, Mark Harris, explained, “For centuries, we have been told not to speak out about [racial violence]. You don’t have to like it. It’s not only my history. This is American history.”

In a further twist, artists of color risk censorship when their work confronts racial taboos, as satire often does. Last summer, California State University Long Beach canceled the widely acclaimed comedy N*GGER WETB*CK CH*NK, which tackles offensive racial stereotypes through a musical routine peppered with racial slurs – a humorous critique of the bigotry lurking in the American psyche.

Suppressing art and literature that engage the difficult and often very uncomfortable subject of race in America does nothing to confront the realities of racial discrimination, police violence, inner city poverty, or rates of incarceration. Discussions generated by cultural works are not going to resolve these problems either, but the conversations may help us speak to each other more effectively, understand our historically determined reactions, as well as imagine better alternatives.

Such conversations are not easy. Cultural institutions and school boards, faced with funding pressures and community demands, often prefer to avoid the inevitable conflicts that race related works provoke, which is all the more reason to support those who take the risk. As the artist behind the controversial painting of Emmett Till said, “it is better to try to engage something extremely uncomfortable, maybe impossible, and fail, than to not respond at all.”