For the latest edition of our Arts Advocacy Podcast, we talked to the bi-coastal artist and photographer Savannah Spirit. Savannah uses Instagram to create, as well as distribute, her photographs among her fan base, curators and potential collectors. Her photographs range from atmospheric self-portraits and nudes to California landscapes and New York streetscapes.

Savannah’s sun-drenched nude self-portraits—a nod to predecessor and pin-up model-turned-photographer Suze Randall, who shot self-portraits for Playboy in 1976—have been repeatedly flagged and removed as ‘obscene’ or ‘inappropriate’ by the social media platforms Instagram and Facebook. A recent solo show of black and white abstract nude self-portraits, Nevertheless, She Persisted, at Mulherin New York, directly addressed her experience of frustration with social media platforms, by printing the censored images and placing them in physical space in a gallery, out of the range of online censors.

Her current solo exhibition I Am a Camera at Undercurrent Projects in New York (Mar 1st – Apr 15th, 2018) presents new works from her ongoing series,”Striped” (2016 – ). The exhibition press release describes the work as…

…a study in light and shadow originally designed to evade the censor bots that have been deleting her social media accounts for the past 2 years. In the photographs, sunlight seeps through the open slats of the windows directly onto the skin of the artist, forming a classical pattern of light and shadow. Using her iPhone as her shutter release, Spirit’s camera becomes her mirror as she manipulates her shape and gesture between shots. Savannah is the camera. The resulting film noir nudes are elegant in form and line.”

We talked to Savannah Spirit about her influences, what she loves about photography apps and how social media has affected her career. Listen to the podcast and read our short interview with Savannah below, after the jump.

***

Social Media, Nudity & Censorship

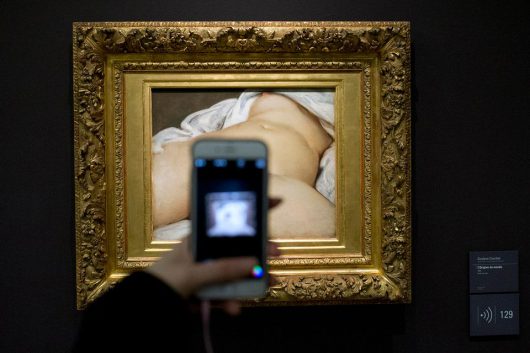

A visitor takes a picture of Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866) at the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris (AP Photo/Francois Mori)

Social media increasingly determines what people may or may not see or read about the world. Artists, who have grown to depend on visual platforms like Instagram (which is owned by Facebook) to share their work, are in a constant battle over the removal of their works and take-downs or suspensions of their accounts. These frequent removals often stem from a vaguely worded no-nudity policy and confusion over what constitutes “artworks” or images of cultural import in their Terms of Service.

That all-too-loosely interpreted wording frequently leads to the flagging and removal of images of historical, artistic or journalistic merit.

In the past, Facebook’s countless removals of images have included artist Frode Steinicke’s posting of Gustave Courbet’s 1866 painting L’Origine du monde (Origin of the World), which depicts a woman’s vagina as the origin of life; a Breast Cancer Awareness Body Painting Project by Michael Colanero that was deemed “pornographic”; drawings of nudes from the page of the New York Academy of Art (later reinstated); and last year, the removal of an iconic Vietnam War-era journalistic photograph.

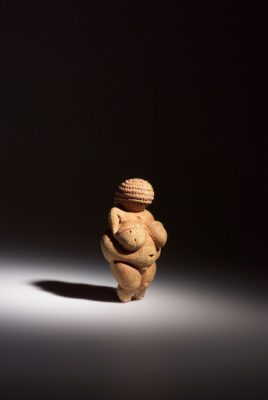

The Venus of Willendorf, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

A recent instance of egregious Facebook removal of an artwork over nudity occurred in December when it banned a user’s image (and subsequent posts of the image, including one by The Art Newspaper) of the famous 30,000 year-old nude statuette known as the Venus of Willendorf that resides in the collection of the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna. This has spurred outrage and a flurry of articles on the problem of Facebook’s arbitrary and ongoing censoring of artworks. A Facebook spokesperson has since apologized for the error; in the meantime, the artist who posted the image is petitioning Facebook to change its algorithms.

While Facebook has admitted the difficulty in creating distinctions between different kinds of images containing nudity, it has done nothing to work with artists, whose problems remain unresolved. Twenty-first century artists, particularly those without global name recognition, depend on social media to distribute, advertise and even sell their work. They are understandably frustrated, but have little recourse and no clear alternatives to using existing social media platforms.

Of course, non-artists have also suffered the removal of images containing nudity and even the suspension of their accounts. In 2011, French primary schoolteacher Frédéric Durand-Baïssas sued Facebook for closing his account after he posted a photograph of L’Origine du monde, charging them with censorship and seeking €20,000 in damages due to his loss of contacts and content, the re-activation of his account and an explanation of why it was closed. Durand-Baïssas’s lawyer posed a key question: “Where does art begin and where does pornography end? That is an interesting debate to have—but Facebook refuses to have it.” A court ruling is expected in mid-March.

***

A Short Interview with Savannah Spirit

NCAC: When did you first decide to post your work on social media and what platform did you use? How did it free you, and which aspects of sharing your work that way were thrilling—or daunting?

Savannah Spirit: In the beginning, I was shooting from the hip, more documentary style, shooting the NY art scene, subway shots, etc., posting on Facebook and Tumblr, then eventually on Instagram. I was shooting the city and the people: fast, un-posed, candid—the thing fit right into my pocket. Mobile photography was freeing and I saw these platforms as a way to reach out to a new audience. Turning the camera on myself took a long time until I was ready for my work to become more of an exploration of self. Something I hadn’t done before. At the time it was thrilling because I wasn’t sure of the work and it was (oddly) a way to get feedback but then it became daunting because of the censorship.

NCAC: You characterize your most recent series of photographs, Nevertheless, She Persisted, as work that “melds together this classical aesthetic while addressing objectification, body-positivity, the female/male gaze and censorship.” Tell us more about that.

SS: In the beginning, when I was posting the pin-ups I was blurring out my nipples, although I felt I was body shaming myself by self-censoring. I didn’t like that. On top of that, it was being deleted anyway. The change in my work came from the frustration of being censored. When I first started shooting the striped work, I was thinking of my body as a shape. Thinking of Imogen Cunningham’s work. I was influenced by the film The Conformist—a particular scene of a woman dancing with light shining through the blinds, the whole room was lit that way. Her dress mimics the room in a chevron pattern. That scene stuck with me for a long time and always wanted to do something in that style. The black and white work is quiet and classical—I’m isolating the body as a shape. It wasn’t about being sexual (the opposite of my pin-up series, which is obviously titillating.) I had been posting my work on social media for some time, so I was comfortable posting the more abstract work. But no matter what I did, the censorship of my images continued.

NCAC: As an artist who uses social media, how dependent have you become on the immediacy of sharing, feedback and distribution? How has social media affected your career? Would the inability to post your work on social media constitute a hardship at this point?

SS: It would be tough for me as an artist to be cut off from this method for sharing my work. Social media, crowdfunding projects and the whole DIY mentality has been an invaluable resource for most people, especially artists, freelancers, musicians and anyone with little money who needs to spread the word about their work. I now have a Patreon account in order to create my own sense of community without the censorship and worry that I’ll be deleted again. Other artists I know who post similar work [with nudity] are just as puzzled. It’s the way most of us advertise our work and businesses now—with a personal touch—but Instagram and Facebook are ruining our game. It’s the best PR and marketing tool there is without spending money, so when you have that taken away so quickly after rebuilding and nurturing a following, it’s tough. So how do I get the work seen? What choices do I have in this new era of self-advertising? When my work is taken down or I see another friend had their work deleted, it makes my heart sink. I expect it now, it comes with the territory.

NCAC: When we last spoke, you had suffered yet another take-down of your Instagram account and a simultaneous suspension from posting on Facebook. How many times has this happened and how do you cope? Has the repeated censorship of your work caused you to change the work itself?

SS: Yes, it has absolutely changed my work. How can it not, at this point? Instagram has removed my account 6 times (recently, 2 times in a single month), and with Facebook it’s been countless shutdowns. A “30 day no posting or liking” slap-on-the-wrist punishment from Facebook is now in effect. It’s frustrating because I spend time building a viewership, and then I have to start all over again. Am I being reported? Probably. Is it an algorithm? Perhaps. It’s like Oz, the man behind the curtain. No one really knows what or why or who, or how this mysterious machine works. It’s the dark side of technology, designed to make you not trust “it” or “them.”

Deja Vu, 2015, archival pigmented inkjet, 20″ x 16″. Photo courtesy of Savannah Spirit

NCAC: Many artists have experienced similar frustration with the Terms of Service (ToS) of private companies such as Facebook and Instagram and resulting censorship. And yet, most artists know that they are testing the boundaries and limits of what those ToS allow. What advice do you have for other artists dealing with this problem? What specific changes would you like to see to the ToS implemented, moving forward?

SS: In order for Instagram (which is owned by Facebook) to be available for all (including children), it has to abide by Apple’s ToS. I understand that, but there must be some simple way to resolve this. I really wish they would hear us and try to find ways to work this out, even reach out to us instead of making it so hard for us to reach their administrators when our profiles are deleted. There is a difference between hardcore porn images (as well as violent and disturbing images) and artwork. There is a huge distinction between the two. Figure out the algorithm for fine art vs porn. I’m pretty sure someone in Silicon Valley can figure out how to do that for us. Or at least take a meeting with some of us. I say to other artists: keep posting, do not stop. Find ways to be clever about how to put your work out there. Make it work for you, not against you. We are not the enemy. Soon, there will be other ways to share our work without the hassle of censorship. I’d create a new platform if I had the means. Right now I wish they’d just leave us be.

Feeling Hollyweird, 2017, archival pigmented inkjet, 9″ x 9″. Photo courtesy of Savannah Spirit