A year into one the most divisive presidencies Americans have seen in their lifetimes, free speech is in crisis. Protests opposing alt-right and other controversial speakers have turned violent on college campuses, museums face threats of violence, artists call for the destruction of work by other artists and outrage is replacing reasoned debate (that apparently outdated darling of liberals).

This article points at the most representative issues affecting artistic freedom in the first year of the Trump administration, including brief commentary on new government policies restricting the circulation of ideas, the ongoing pressures of private funders, and a new and powerful trend: grassroots and netroots groups calling for the destruction of work that refers to disturbing histories.

A New Culture War?

If this is a new culture war, it is very different from the 1990s when conservative legislators attacked “degenerate” art that had received public funding. For one, cultural conflict is playing out in a field much broader than the arts and involves a multiplicity of groups in conflict, not simply the religious right versus the art world. It reveals an art world fractured over representing history and race, campuses that refuse debate on issues some students and faculty find too offensive to talk about, and an online environment where “unfriending” is a frequent response to non-orthodox opinion.

Current challenges to artistic freedom feature familiar actors including government and private donors, as well as new demands for censorship coming from the left. Government, with some notable exceptions, plays a role not so much in direct censorship as in setting the structural conditions delimiting the circulation of ideas. Political moves such as the “Muslim ban” or the pulling out of UNESCO because of the agency’s position on Palestine adversely affect individual artists as well as resonate broadly in the sphere of cultural production. The Damocles sword of congressional cuts is ominously swaying over the National Endowment for the Arts, after President Trump proposed a budget eliminating the agency entirely; private funders run for the hills every time controversy hits, as it did over the Public Theater’s production of Julius Caesar and, as usual, wield their financial clout to stifle political ideas they dislike.

However the most notable development of the last year has come from the left. The divisive rhetoric advanced by the President reverberates through the world of culture exacerbating conflict, especially around work exploring racism, police violence or the political standoff in the Middle East. What is new is that sections of the cultural left, having perhaps reached a level of extreme desperation at the corporate-populist takeover of the country, are increasingly abandoning all stakes in free speech supposedly in the service of advancing ideals of social justice. Perhaps desperate times need desperate measures, but the angry social-media enhanced attacks on art institutions and artists daring to deal with historical trauma that feel like political action may actually be a poor substitute for it. In a kind of participation-lite, cultural expression is increasingly called on to bear the weight of deeper grievances: racism, discrimination, gender and social inequalities. But a purely cultural response – whether the removal of 1930s historical murals, the banishment of white artists dealing with histories of oppression or the addition of warning labels to art that records the male gaze on female bodies – will not resolve those grievances.

In 2017, speech that offended group orthodoxies was subject to critique and threats from all sides. Free speech as a core value was increasingly abandoned by its traditional liberal/left supporters and hoisted as a banner of white supremacist racist speech. If there is a defining characteristic of our first year of Trump, it is the demise of nuanced thinking. A strange new puritanism is rising, where doubt has no place, where those that disagree with you are banished, and where argument is always power struggle never the quest for truth. For art, which is defined by the multiplicity of meanings it may generate, some of them contradictory, some questioning received pieties and taboos, this is very bad news.

The Role of Government Policies and Regulations

From the demise of net neutrality to extreme media consolidation, both accomplished by a Trump-appointed Federal Communications Commission, and including a range of legislative changes in-between, structural changes in the United States promise long-term shifts in who is able to be heard and who shapes public opinion. What is affected is not so much the capacity for art production, but the platforms where art can be seen, how art can circulate and who can participate in the cultural economy.

Take for instance the so-called “Muslim Ban”. The legislation would deny entry to the US to citizens of a “blacklist” of eight (initially seven) Muslim-majority countries. One of the President’s first legislative efforts, the ban has closed off the US to artists that may seek refuge from repressive regimes and has made the visa process long and cumbersome even for those eligible to come into the US. The logistical delays often mean those artists cannot attend the cultural events and programs to which they have been invited. The long-term effects will inevitably mean further isolation and socio-cultural retrenchment. The visa ban is not targeted at specific artwork, yet deeply affects artists and the culture at large and potentially limits the range of art available to the American public.

Direct Censorship

Ghaleb Nassar al-Bihani, Blue Mosque, 2016, watercolor.

While structural changes and policies have the longest term impact, occasionally the current administration slips into interventions directly taken out of totalitarian handbooks. In November 2017, for instance, the Department of Defense issued a new directive declaring that artwork by Guantanamo Bay detainees will henceforth be held by the government as its property. This happened just as the gallery of The John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York was holding an exhibition of such art called Ode to the Sea: Art from Guantanamo Bay. The John Jay show presented a glimpse into the mental world of the detainees and that glimpse is not of demonic plans of blasting buildings, but of peaceful seascapes. Could then the men held at Guantanamo be just as human as ourselves? And could the moment of empathy experienced when sharing the image of a boat floating on tranquil seas also bring home the horror of imprisoning a person for an indefinite length of time, away from family and children, with no proof of crime? Clearly these are questions the US government would prefer not to face, nor to allow the public to face: easier to just hold the work captive. It is not just the detainees that are affected by the new directive – it is the American public whose access is curtailed to what government wants it to see. This is the very same public in whose name Guantanamo was created. So much for democracy.

Exacerbation of Conflict: Social Polarization

Aside from structural policy changes and direct suppression of artwork, the new administration has exacerbated long standing conflicts and has lead to the further polarization of an already split nation. Such polarization affects conversations about race and racism, traumatic histories, indigenous rights, sexuality, class, and the Middle East, among others.

On some of the issues the President sets the tone more powerfully than on others, but the generally angry and accusatory tone coming from the White House resonates through all aspects of the public sphere, including the art world. The President’s tweets have included re-tweets of extremist organizations’ anti-Muslim video hoaxes, a condemnation of protests against racism and white supremacists as just as bad as the lethal violence of the supremacists themselves, and a mocking reference to a Democratic Senator as “Pocahontas” at an event honoring Native American veterans. It is thus not surprising that a loud, openly racist, nationalist and white supremacist alt-right sees itself aligned with the President and his top advisors. The administration has done very little to correct that impression.

While Trump’s tweets, with all their social repercussions, could be seen as distraction techniques, divisiveness also informs the President’s policy decisions. The move to pull the US out of UNESCO because of the cultural and educational organization’s positions on Israel and Palestine, for instance, has fed directly into the political polarization over the situation in the Middle East.

It is harder than ever to deal with the Israeli/Palestinian conflict in artistic representation. Any art institution that displays art about the conflict – or even art that is created by Israeli or Palestinian artists – needs to carefully navigate intense pressures coming from right-wing pro-Israel groups and calls for boycott from supporters of the cultural BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement.

Right-wing activists regularly paint individuals and institutions who are critical of Israeli government policies as anti-Israel or even anti-Semitic in an effort to silence them. Many of these efforts are successful. In October 2017, after accusations of supporting “anti-Israel” programming, the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) in New York cancelled a reading of Rubble Rubble, a play by Dan Fishback, solely because of the playwright’s association with the organization Jewish Voice for Peace.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the cultural BDS movement threatens to boycott any institution that hosts work which is supported by Israeli government funds. Such was the case with the 2017 Lincoln Center presentation of David Grossman’s To the End of the Land, a play which explores the entanglement between private lives, war and history in Israel between 1967 and 2000. The author, Grossman, is an outspoken critic of the Israeli government and its cultural policies, as well as a prominent peace activist. In his 2010 New York Times review of the novel, upon which the play is based, author Colm Tóibín wrote: “To say this is an antiwar book is to put it too mildly… This is one of those few novels that feel as though they have made a difference to the world.”

Nevertheless, a large group of prominent New York cultural figures – playwrights, filmmakers, actors and directors, including Caryl Churchill, Wallace Shawn, Lynn Nottage and Taylor Mac – demanded that Lincoln Center cancel To the End of the Land because the production received Israeli government funding. Lincoln Center proceeded with the play. Cancelling performances would have deprived audiences of an important critical voice coming from within Israel, as well as of the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the human side of a tragic socio-political conflict.

Any cultural producer considering content related to the Middle East or exhibitions featuring artists from the area needs to prepare to face protests. As always, the worst consequence of such controversies is that, instead of daring the often ugly and ad-hominem invective of protesters, cultural producers may censor themselves and avoid dealing with the issue altogether. That outcome is even more likely when it is an institution’s major donors who object to the work as was the case at AJHS.

Funding Pressures

Contrary to the 1990s, in the current cultural conflict the focus is not on government funding the arts. The President did try to erase the National Endowment for the Arts from existence in his budget blueprint, not in retaliation against offense (his outrage being mostly reserved for the media), but in an effort to eliminate “waste.” Congress has since voted to continue funding the agency. Federal funding for the arts is so diminished and so conservatively allocated already, it is hard to get even right-wing conservatives excited about its uses. Indeed, almost all recent controversies over art have taken place in private institutions and, where funding pressures have been used, they have originated with private funders.

Private funders and the pressures they exercise have long been a problem in a country which prefers to leave artistic freedom to the whims of the free market than to provide public support for art. Even when not bent on reinforcing their political point of view, private funders become skittish when their brands get attached to controversial content – especially if that content is critical of those in power. Bank of America and Delta Airlines rapidly withdrew their support of New York’s Public Theater, when the summer 2017 production of Julius Caesar was attacked for its present day allusions to President Trump. The Public stood firm in the face of funding pressures, individual hecklers and even death threats. Other corporate donors quickly stepped in to fill the funding gap. But could a smaller and less venerable institution take a similar risk? Pre-emptive self-censorship for fear of lost funding is hard to document, but familiar to any leader of a cultural institution in the US.

Traumatic Histories and the Political Left

While funding pressures, government censorship and controversy around the Middle East are all familiar and persistent threats to artistic freedom, a brief look at the recent drumroll of high-profile art controversies points at a newly powerful actor: grassroots and netroots efforts coming from the political left that call on institutions to refuse a platform to art they find disturbing or ethically objectionable.

Left wing protest against exhibitions and art world inequities is certainly not new (the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1969 show Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America,1900-1968 comes to mind, as do the actions of the feminist Guerrilla Girls Collective in the 80s and 90s), but their power to mobilize a young cohort of artists, their frequency, and their influence have increased to the point of creating a sea change in the art world. A rising nationalist and racist alt-right and a divisive presidency, complete with accusatory tweets, attacks on mainstream media and a failure to take a firm position against racism or police violence, contribute to the anger fueling those protests.

High profile art controversies in 2017 came at the rate of one every two to three weeks with targets expanding to a point where a white artist, because of the color of their skin, is not only criticized when making work about historical trauma affecting minorities, they – and the exhibiting institution – become subject to personal threats. Calls for censorship and the destruction of the artwork come from groups that previously were staunch supporters of artistic freedom (when this freedom was threatened by the religious right). They justify censorship now in the name of social justice and of protecting minorities from the pain certain historical representations may provoke.

Who can represent traumatic history?

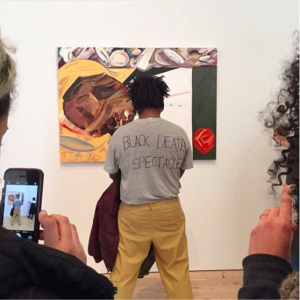

Parker Bright: Whitney Biennial, silent protest blocking Dana Schutz’s painting ‘Open Casket.’

The year’s defining controversy was around Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, based on the iconic historical photograph of the 14-year old’s mutilated body in its casket. Tortured and lynched in 1955 because a white woman claimed he offended her with sexually suggestive remarks, Till became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement after his mother decided to publicly release an image of his corpse in its casket. Schutz’s work was included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial along with many works on race-related issues by artists of color. The Biennial was deliberately participating in the national conversation about race and police violence against black men.

Schutz’ painting, much as it aligned with the general themes of the Biennial, provoked a firestorm of calls for removal and destruction: because it was painted by a white woman, because it “appropriated” a painful history which did not belong to her, because it re-traumatised viewers… A subsequent mid-career retrospective of the artist at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston was challenged by a group of artists and activists, who asked for its cancellation, solely because of Schutz’s transgression in creating the Emmett Till painting (the work was not part of the ICA exhibition).

To their credit, neither the Whitney nor ICA bowed to pressures for censorship. The Whitney added a statement from the artist to the wall text accompanying the work and also invited poet and author Claudia Rankine, founder of the Racial Imaginary Institute, to organize a public panel and conversation about the controversy. The broader debate around the work – which took place across print media, the internet, as well as at the Whitney panel – was passionate and angry, insightful and revealing of deeper conflicts. It revealed deep grievances and fissures within the art world. If anything, it proved how productive controversy could be if an institution is true to its mandate and stands by curatorial decisions. Consensus has not been reached (and is unlikely to be reached anytime soon), but positions have been developed, heard and challenged.

Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012), Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, before it was dismantled.

A month or so after the Whitney controversy, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis faced questions and then loud protests over a new sculpture to be installed in the large public space in front of the institution. The sculpture, which looked somewhat like playground equipment, was in fact a composite of 7 gallows used in executions by the US government over the past 200 years. Conceived by socially-engaged multimedia artist Sam Durant, the sculpture, titled Scaffold, sought to draw attention to the death penalty and its effects.

What fired up the controversy was the inclusion, among the historical gallows structures, of one that had been used in 1862 to execute 38 Dakota men about 80 miles away from the Walker in Mankato, MN. Minnesota has the largest Native American population in the country and when some Dakota nation members recognized the Mankato gallows in sculpture, they claimed deep emotional disturbance, the sense of being traumatized by the work.

Just days before the official opening of the sculpture to the public, the director of the Walker, Olga Viso, issued a lengthy apology for “any pain and disappointment that the sculpture might elicit” and promised to “provoke discussion about how the Walker can strive to be a more sensitive and inclusive institution.” This apology, rather than acting as a bridge of reconciliation, sparked a wave of protests against the work. Just days later, representatives of the city, the Walker, the artist and Dakota elders, met and agreed that the sculpture would be removed and disposed of in any way the Dakota wanted, in addition all intellectual property rights to it would go to the Dakota, so that it would never be displayed again, anywhere.

Americans’ relationship to the history of racial violence is as mixed as their racial heritage, as author Zadie Smith noted in response to the Dana Schutz controversy. The history of race in America is one of racial impurity and intermixture and “even when Americans are not genetically mixed, they live in a mixed society at the national level if no other. There is no getting out of our intertwined history.” Yet, in this divisive and racially charged historical moment, lines of opposition and conflict are quickly drawn and policed by anger. These lines demand purity, clarity and an unambiguous distribution of historical guilt and victimhood. One of the protests signs in front of Scaffold read “No Conversation” – a rather chilling demand to stop discussion and just take down the offending work.

A major component in recent controversies has been the personal narrative of pain and trauma. The Walker found it hard to stand by Scaffold when Dakota in the community began to talk about the pain they experienced when looking at the work. Listening to emotional experience is a welcome recognition that such experience has cognitive value, and a certain type of reasoned debate is linked to education and class and excludes those who are socially marginalized. However, relying on emotion-as-argument mirrors the international rise of populism and its gross manipulation of base sentiment. Appealing to feelings is a politically dangerous strategy.

Donald Trump and Europe’s leading extreme right politicians rose to power appealing to feelings of disaffection, anger against immigrants, nationalism, or economic anxieties. Manipulating these emotions are what populist politicians have always done well – unfortunately at a high cost to society at large. It is thus disturbing to see that feelings of pain are at the center of increasing numbers of censorship campaigns coming from the political left. Whereas emotional response should not be dismissed, it is dangerous to let it have the final word. A conversation that takes into account both emotional response and reasoned argument is more necessary than ever. The Walker missed the opportunity to lead such a conversation.

Public universities have faced many recent calls to remove or cover murals that evoke emotional responses to historical trauma.The murals in question often date back to the early 20th century, most of them created through the art project of the government’s Works Progress Administration agency. In an effort to provide jobs during the Great Depression, WPA employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors in large arts projects. Some murals were realistic, others depicted the grandeur of the American landscape, and quite a few were politically charged and idealistic, focusing on labor and its struggles. 1930s Conservatives, irked by representations of workers and class disparity and the occasional appearance of Karl Marx, opposed government funding for the program.

Today, however, complaints – and even calls for destruction – are coming from very different quarters. Some claim the works whitewash and romanticize a brutal history and that, in representing disenfranchised groups in a position of subjugation they reinforce a hierarchy of oppression; others, however, just demand not to be reminded of that painful history.

In the summer of 2017, students at the University of Indiana-Bloomington renewed demands for the removal from view a portion of a 1930s-era mural by Thomas Hart Benton because it depicts a Ku Klux Klan rally. The 22-panel mural shows moments of Indiana history – the ugly parts along with the good. It is by no means a celebration of the KKK. Yet the petition to remove them argued that exposing students and faculty of color to the image of the KKK is a racist act. In response, the university kept the murals in place but decided to only use the space for a gallery and public lectures, not as a classroom.

In the summer of 2017, students at the University of Indiana-Bloomington renewed demands for the removal from view a portion of a 1930s-era mural by Thomas Hart Benton because it depicts a Ku Klux Klan rally. The 22-panel mural shows moments of Indiana history – the ugly parts along with the good. It is by no means a celebration of the KKK. Yet the petition to remove them argued that exposing students and faculty of color to the image of the KKK is a racist act. In response, the university kept the murals in place but decided to only use the space for a gallery and public lectures, not as a classroom.

Why is art such a target in the first place? One possible answer is that art exhibitions are easy to attack. Not only do art institutions claim they are serving the community, they are deeply connected with – and dependent on – artists who see themselves as social activists. Attacking highly visible art institutions also gets press attention and provides a visible platform. What underlies all this pain and anger against artwork is much larger than any artwork or exhibition. Cultural expression is called on to bear the weight of deeper grievances: racism, discrimination, social inequalities. However, any kind of purely cultural resolution – the ban on the use of images relating to oppressed cultural minorities (if such a thing is even possible) or the placement of safety barriers between audience and disturbing artwork – is unlikely to contribute to solving the deeper problems of discrimination, racism and violation of human rights.

Participation-lite: Social Media Activism

Besides the high profile of their targets, protestors also take advantage of the “cheap speech” provided by the Internet and social media. The low cost of participation in online activist campaigns is a double-edged sword: on the one hand it gives a voice to those whom previous gatekeepers of culture (publishers, academic or art institutions) have kept out; on the other hand it demands only a kind of participation-lite.

Participation-lite is problematic as it engages potentially large numbers of people in exercising powerful pressure without always understanding the issues in depth or thinking through conflicting considerations. The Change.org petition asking the Guggenheim Museum to remove two videos of performances including animals from its show about Chinese conceptual art, for instance, gathered some eight hundred thousand signatures within a week. It was easy to sign the petition and to feel you were defending animals. Yet some of the co-signatories were not aware that the performances they were outraged about were not staged at the Guggenheim and that the work in question was simply the documentation of events that had happened decades ago.

Another recent participation-lite petition asked the Metropolitan Museum to reconsider its display of a Balthus painting in light of the current revelations of systemic sexual abuse of women in the culture industries. Although the petition only gathered about ten thousand signatures, it was broadly covered and amplified in the media. The Balthus is staying, but the action demonstrates how every societal problem could find its symbolic equivalent in the museum – and how easy it is to start an art world controversy. Removing the Balthus would, of course, do little to change the gender-biased relationships of power that underlie the sexual abuse of women. Indeed, it may even do harm by playing into a kind of sexual puritanism that has traditionally been used to demonize female sexuality.

Crisis

The key word of the last year has been listening. It has also been the most acutely felt lack. There is ubiquitous lament over ideological and internet-generated bubbles and, simultaneously, a reinforcement of the boundaries of those bubbles. The Trump Administration is partly a symptom of this process of national tribalization and also a major factor in exacerbating the process. Whereas there is a clamor of voices, artistic and others, the platforms that have broad visibility beyond specialized audiences are few and are under intense scrutiny. Speech that offends orthodoxies is subject to critique and threats from all sides. Free speech as a value is increasingly abandoned by its traditional liberal supporters and hoisted as a banner of white supremacist racist speech. We are at a true moment of crisis – in the sense of deep change. Where we go next is not yet clear. But surely, our work as advocates for artistic freedom has become both more challenging and more necessary.

An expanded version of this article originally appeared as part of the Freemuse INSIGHT series edited by Marie Korpe.