Does an artist’s race disqualify them from engaging certain subjects?

In recent months, artworks that address the socially volatile issues of police brutality and racially motivated violence have been in the spotlight. However, the critique, discussion and outrage surrounding these works have not focused on their quality, their meaning, or the intentions behind them—focus has shifted instead to artists’ racial backgrounds and whether they have the right to tell a story specific to a race or ethnic group to which they do not belong. Accusations of ‘cultural appropriation’ have become commonplace. This outrage, expressed with unvarnished acrimony on social media, gathers steam quickly, and once consolidated, can be leveraged to directly challenge individual artists and the institutions that present their work.

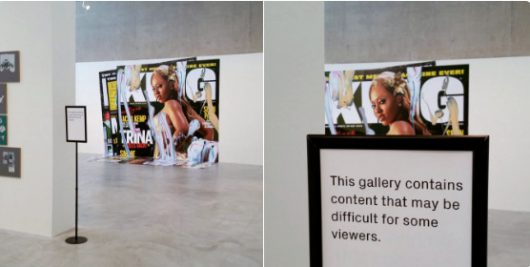

Kelley Walker’s work based on a King Magazine cover in ‘Kelley Walker: Direct Drive, Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis.’. (Photo above by Danny Wicentowski) before and after protests.

Last fall, protests and calls for a boycott broke out over Kelley Walker’s exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Missouri. Several of Walker’s works, for which he appropriates images of the black body from photographs of Civil Rights-era protests and hip-hop magazine covers, prompted widespread calls for their removal. Black artists, community members and museum staffers pressured the museum to modify the exhibition by putting up a wall to enclose the offending works, and signage to warn viewers. Eventually, under pressure, the show’s curator resigned.

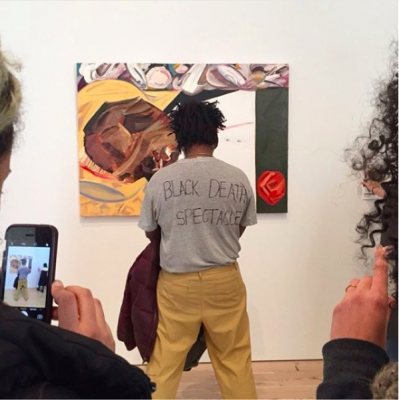

Artist Parker Bright’s silent protest at the Whitney Biennial, blocking Dana Schutz’s painting ‘Open Casket.’

When the Whitney Biennial opened in March, a painting by Dana Schutz, based on an iconic photograph of the mutilated body of Emmett Till lying in his open casket, sparked protests, a petition, and a social media frenzy. Rather than cave to pressure to remove the work or destroy it, as one open letter demanded, the Whitney stood by the artist and their decision to display the work; they respected the rights of protestors, including artist Parker Bright who stood, daily, blocking the view of the painting while wearing a t-shirt with the message ‘Black Death Spectacle.’ They partnered with Claudia Rankine’s Racial Imaginary Institute and held a public forum, thus opening the debate further.

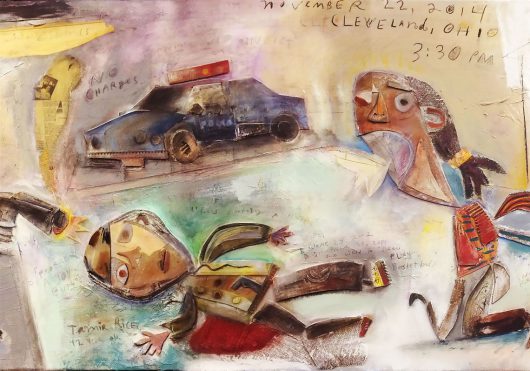

But more often, and increasingly, artists and institutions bow to the demands of critics and protestors, rather than stand their ground and debate. Recently, Tom Megalis submitted a painting, Within 2 Seconds, the Shooting of Tamir Rice, depicting the shooting by police of 12-year-old Tamir Rice to a juried arts festival in Pittsburgh; the painting was accepted, but when Megalis posted an image of it on Facebook, it was met with outrage and derision, despite his earnest intentions. He has since withdrawn the painting.

Tom Megalis: ‘Within 2 Seconds, the Shooting of Tamir Rice’

The cumulative effect of these protests, online and off, appears to have made it more difficult for individual artists and institutions to stand their ground while entering into and sustaining any kind of fruitful dialogue. In late May, Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center became the center of a heated controversy over Scaffold, a massive 2012 work by Los Angeles artist Sam Durant meant to create awareness about capital punishment and its disproportionate effect on people of color. Scaffold is based on designs for gallows used for seven U.S. state-sanctioned executions, including that of abolitionist John Brown and 38 Dakota men hung in Mankato, Minnesota in 1862. The work was not discussed in advance with the local Dakota community, and its installation was met with a protest and demands that the work be dismantled.

After a meeting between Dakota elders, Sam Durant, Walker Art Center executive director Olga Viso, members of the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, and city government officials, a determination was made: A Native-owned construction company will oversee the dismantling of the sculpture; the wood will be taken to a site near Fort Snelling, where Dakota people were imprisoned after the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War that resulted in the executions, and ceremonially burned. As part of the agreement, Durant will never re-create the piece, and will transfer his intellectual property rights to the Dakota Nation.

In all of these cases, questions have focused on whether a white artist has the right to represent historically traumatic moments from the past of other racial and ethnic groups. In none of these cases was it the artist’s intention to cause pain—quite the opposite. And yet, in each case, with the exception of the Schutz painting at the Whitney Museum, due to the mis-fire of message and audience, a furious outcry on social media—a public shaming and calling-out of the artist—has led to the sequestration, removal, withdrawal, and now destruction of works of art due to the offense taken over the race of the artist. More to the point, these protests don’t pose questions; they assert the premise that white artists do not have the right to engage issues, histories, stories and pain that they themselves have not experienced and have, in fact, contributed to as the oppressor in a culture that systematically and structurally privileges white people.

Sam Durant, Scaffold.

While critiquing or protesting artworks is a vital part of a healthy democratic society, cultural institutions that bow to demands to remove or destroy works endanger our ability to maintain a public sphere where ideas and societal problems can be freely discussed and identified. Not only does silencing and suppression set a dangerous precedent for the culture at large, it does nothing to confront the realities of racism. As noted by NCAC a few years ago when the poet Vanessa Place, whose long-running social media performance—tweeting the full text of the novel Gone With the Wind—sparked violent criticism of the project as a racist appropriation:

The cultural atmosphere evidenced by the events […] is chilling to any creative artist or institution that may consider approaching difficult questions around race, sexuality or politics. It makes real debate about emotionally charged issues over which we often disagree nearly impossible. Unless they develop strategies to manage conflict and disagreement productively, cultural institutions will operate as echo chambers under the pall of a fearful consensus, rather than leaders in a vibrant and agonistic public sphere.