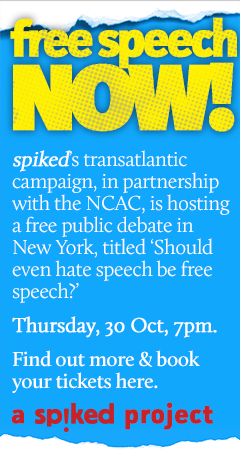

Read about the Spiked public debate in NYC on October 30, 2014.

To outsiders, 21st century Britain must look like a pretty liberal country. We don’t imprison people for their political opinions. We no longer seek to ban so-called “obscene” novels, as the authorities tried to do with D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” when the unexpurgated version was first published in 1960. We got rid of our blasphemy laws in 2008. The British Board of Film Classification now okays the cinematic release even of films that contain explicit sex, something it would never have done in the past. And even our notorious libel laws are finally being reformed to make it harder for people to make a claim of defamation.

Yet all this legal liberalisation, all this rewriting of laws that governed the publishing worlds in Britain for decades, can be deceptive. For while old-fashioned forms of censorship are being rethought, newer, more insidious forms of censure and silencing are taking their place. We may no longer punish people for publishing saucy novels, but we do still squash material that is judged to be “offensive” and arrest and sometimes imprison individuals who are judged to have expressed “hateful” ideas. And while the press can breathe a (small) sigh of relief that our chilling libel laws are being reformed, it nonetheless finds its liberty to publish and be damned threatened by new forms of press control. Put the champagne on ice — for no sooner has some of Britain’s old censorship been elbowed aside than even more problematic forms of censorship have risen up.

For a taster of how new forms of censure have hurriedly filled the gap left by the decline of old censorious laws, consider this. In March 2008, England’s archaic blasphemy laws, which outlawed any “contemptuous, reviling, scurrilous, or ludicrous matter relating to God, Jesus Christ, or the Bible”, were finally abolished. This was a step forward for free speech. Yet in the exact same month, a series of television commercials was banned on the basis that it might offend Christians. The commercials described a brand of hair products as “religion for the hair” and featured beautiful women in lingerie clasping rosary beads to their bosoms. How could these ads be banned when there was no longer a law against blaspheming against God or Christ? Because of a body called the Advertising Standards Authority (A.S.A.), whose job is to police and punish the giving of offence by businesses, individuals, and anyone else who advertises things.

The A.S.A., set up in 1962 but having become increasingly censorious in recent years, banned the hair-product commercials after it received just 23 complaints about them. It ruled that the ads were “offensive” to Christians and thus must never again be shown “in their current form.” This isn’t the first time the A.S.A. has demanded the withdrawal of commercials that offended infinitesimally small numbers of people. It banned an advert for an airline that showed a Britney Spears-style schoolgirl after receiving 13 complaints saying it was “derogatory” to women. It banned an advert for a supermarket which showed a girl taking the salad out of her hamburger before eating it, after receiving 11 complaints that the ad promoted “unhealthy lifestyles.” (You mustn’t blaspheme against healthy living in modern Britain.) The A.S.A empowers the sensitive, allowing the offended feelings of tiny groups of people to take precedence over the right of the rest of us to see and hear things and make up our own minds about whether they have any moral worth.

This tale of the 2008 banning of an advert that offended a tiny number of Christians just days after the UK abolished its blasphemy laws reveals a broader truth about censorship in modern Britain. It shows that censorship is increasingly being outsourced to the mob, to agitated sections of the public; and it confirms that guarding individuals from feeling offence is now one of the main aims of the censorious class. It reveals why Britain has liberalised its more archaic censorship laws — not because the British state has become a liberty-loving entity, but because it now finds it more convenient to censor things in the name of “the people” and in the name of protecting the fragile from offence.

This tale of the 2008 banning of an advert that offended a tiny number of Christians just days after the UK abolished its blasphemy laws reveals a broader truth about censorship in modern Britain. It shows that censorship is increasingly being outsourced to the mob, to agitated sections of the public; and it confirms that guarding individuals from feeling offence is now one of the main aims of the censorious class. It reveals why Britain has liberalised its more archaic censorship laws — not because the British state has become a liberty-loving entity, but because it now finds it more convenient to censor things in the name of “the people” and in the name of protecting the fragile from offence.

Another example of the so-called “democratisation” of censorship can be seen in the work of the British Board of Film Classification. Originally called the British Board of Film Censors, until it adopted its softer-sounding name in 1984, the job of the B.B.F.C. is to watch and discuss every film before we the British public are allowed to see it. It fundamentally decides whether a film may be released in Britain and also what age groups should be allowed to see said film. In recent years, the B.B.F.C. has, like many other institutions, become seemingly more liberal. So where once it sought to “shape public morality,” through restricting the availability of depraved and pornographic films, now its leaders say they want merely to “reflect” public morality. And so they hold regular focus groups to see what the public thinks is acceptable and unacceptable in modern film. “We want to reflect what the public feels, not tell it what to think,” the modern B.B.F.C. says.

Yet this gives rise to new forms of censure. Like the A.S.A., the B.B.F.C. censors things on behalf of “the public” now — or at least, on behalf of those it has consulted in its focus-group discussions. In 2012, it told director Ken Loach that he had remove eight of the 15 uses of the word “cunt” from his movie, “The Angel’s Share,” if he wanted it to get a 15 certificate, on the basis of its findings about expletives in its focus-group discussions. Apparently, those aged 15 and over may hear the c-word seven times, but not 15 times. It demanded 17 cuts from the 2010 horror film, “I Spit On Your Grave,” on the basis that the kind of things shown in that film ran counter to what its focus groups said was acceptable in modern cinema.

In 2011, it refused to classify the D.V.D. version of another horror movie, “The Human Centipede II,” again on the basis that it showed things that might offend “public sentiment.” The movie could “deprave or corrupt a significant proportion of those likely to see [it],” the B.B.F.C. said. Its refusal to classify this D.V.D. made it illegal for anyone to sell it or hire it out. So even in supposedly liberal 21st-century Britain, film censorship remains a fact of life, though now the guardians of movie morality claim to be acting on behalf of concerned citizens and insist that they merely “reflect what the public feels.”

The outsourcing of censorship to sections of the public, and the sacralisation of non-offence as the greatest virtue of modern Britain, means that even art can be banned. The famous “Lady Chatterley” legal case of 1960, when a jury refused to support the state’s attempt to ban Lawrence’s sexual novel, is seen as the moment in which modern Britain was born, when the old censorious elite was elbowed aside by a new era of openness. Yet literature and art remain at threat, again from accusations of offensiveness. In recent years in Britain, numerous arts institutions have practised self-censorship in order to avoid inflaming public anger. The Barbican Theatre in London cut out sections from its production of “Tamburlaine the Great” for fear of offending Muslims. The Royal Court Theatre in London, famous for being daring, cancelled a reading of an adaptation of Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata” that was set in a Muslim heaven, again worried that it would upset the Muslim community. The City of Brighton in the South of England has restricted the playing of Jamaican dancehall music in public venues, on the basis that some of this genre has homophobic lyrics that could cause offence to gays. More recently, an art exhibition called “Exhibit B” was shut down by protesters who said it was offensive to black people.

So the restriction of art is tragically alive and well in Britain today. Only now, it is not stiff-upper-lipped, anti-sex officials who are clamping down on what they unilaterally judge to be outrageous material — rather, often ostensibly liberal institutions are censoring themselves in a pre-emptive fashion. This, too, is a logical consequence of today’s empowerment of the sensitive and the “democratisation” of censorship. This process leads inexorably to a situation where we are encouraged to police ourselves and to hold back from saying or showing potentially offensive things.

Modern Britain prides itself on not practising political censorship. Our leaders regularly denounce countries that punish and imprison people for holding the “wrong” political or moral views. And yet morally motivated censorship still takes place in Britain, again under the umbrella of outlawing offensiveness. In recent years certain religious groups have been banned from expressing viewpoints that might offend homosexuals. So in 2012, the Mayor of London unilaterally banned an advert from London buses which suggested that it is possible to be “treated” for homosexuality. The ad, placed by an evangelical Christian group, was “offensive,” the Mayor said. A year later, the High Court decreed that the ads should remain banned because they were capable of causing “grave offence.” Here, the right of expression of a religious group was demolished by the authorities in the name of protecting gay communities from offensiveness.

There have been other instances where actual political and moral sentiments have been punished. In January this year, a Christian street preacher was arrested in Dundee, Scotland, after he was judged to have caused offence by saying that homosexuality was a sin. He was arrested under Scotland’s Offences (Aggravation by Prejudice) Act 2009, which can be used to punish prejudicial speech in certain settings. In England and Wales, numerous people have been arrested and punished under hate-speech legislation for saying things that others find offensive. In 2012, three Muslims were arrested in the north of England for handing out anti-gay leaflets. In 2010, a man was arrested for handing out anti-Muslim leaflets which argued that Muslims were responsible for bringing heroin to Britain. In 2012, a member of the far-right British National Party was given an eight-month prison sentence for writing an offensive blog post about immigration — he argued that there were too many foreigners in Britain and accused the government of adopting a policy of “darkies in, whites out.” “Darkies” is an offensive word for black people.

We can agree that these viewpoints, whether they’re saying gay sex is a sin or Muslim immigration is dangerous, are repulsive, but they are nonetheless merely viewpoints, the moral convictions of certain individuals. To punish people simply for holding such views is a clear case of political and moral censorship, though it is carried out under the guise of restricting “hate speech” that might cause offence.

Other laws ostensibly designed to discourage the giving of offence have been used to punish political sentiment. So in 2012, a young Muslim man was found guilty under the Communications Act 2003 of being “grossly offensive” when he posted on his Facebook page a message saying he hoped all British soldiers who die in Iraq will “go to hell.” He was sentenced to 240 hours’ community service simply for expressing this hotheaded, offensive political view. Under the Terrorism Act 2006, it is a crime to “glorify terrorism.” This can mean simply expressing admiration for groups deemed by the British state to be terrorists, including Hamas in the Middle East and the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka. To some people, these are legitimate political organisations. Restricting the expression of support for them is political censorship. In 2007, a young Muslim woman was given a nine-month suspended prison sentence for glorifying terrorism, partly for some poems she wrote that expressed admiration for al-Qaeda.

So we may not ban political parties or burn political manifestos — but through a liberal interpretation of hate-speech and anti-terrorism laws, we do still punish individuals whose only crime is to possess offensive or non-mainstream moral and political views.

The expression of hateful comments online is now strictly policed by the British authorities. In 2012, a Welsh student was imprisoned for 56 days for saying racist things on Twitter. In 2010, a man was found guilty under the Communications Act of being “grossly offensive” after he *joked* on Twitter about blowing up an airport. Eventually, in 2012, his conviction was quashed on appeal by the High Court. The police now openly monitor social-networking sites in search of offensive or hateful material. After the Scottish tennis player Andy Murray was subjected to personal abuse on Twitter during the Scottish referendum in September, Police Scotland said it would “take action” against abusive tweeters because “there is no place for personal abuse of any kind on [Twitter].” This is an extraordinarily censorious decree. British officials slam foreign regimes that police expression on Twitter, yet the British authorities do the very same.

Then there is press freedom. This, too, is in a pretty parlous state today. Yes, England’s stringent libel laws, which for so long had a chilling impact on the press, making it reluctant to break big, muckraking stories for fear of being sued, are now being reformed (slowly). But the Leveson Inquiry into phone-hacking at the “News of the World” has introduced new forms of press monitoring and control. It has proposed the introduction of a new press regulation body that would be underpinned by statute, which would be the first time the state had openly interfered in the press in Britain for more than 300 years. Strikingly, the Leveson proposals are also justified in the name of “the public” — in this case, in the name of ordinary citizens who have been the victims of press stings. Once again, censoriousness is cynically justified by the state as a way of protecting the weak from victimisation by the press, publishers and others with outré views.

So what we have in Britain today is the emergence of whole new layers of speech-policing, with certain images, words, films and thoughts being punished and censored. And it is all done in the name of combatting hate, meaning it can be presented as “progressive,” and in the name of protecting sections of the public from offence, meaning it can be presented as “democratic.” But censorship can never be progressive or democratic. It is the opposite of democracy, in fact, since it is fuelled by a view of the public as fickle and impressionable, and by a belief that it falls to small numbers of enlightened people to control public debate on our behalf. This is elitism, not democracy. There are no mass, street-based demands for censorship in Britain today – rather, the easily offended and other quite small constituencies are being used as a stage army by officials who, for all their modern liberal pretensions, still have a burning urge to behave as the moral guardians of the public sphere.