Introduction: Robert Atkins and Svetlana Mintcheva, “Censorship in Camouflage”

1. Introduction: Robert Atkins, “Money Talks: The Economic Foundations of Censorship”

2. Ruby Lerner, “Private Philanthropy and the Arts: Does Anybody Want An Artist in the House?”

3. Lawrence Soley, “Private Censorship, Corporate Power”

4. Siva Vaidhyanathan, “American Music Challenges the Copyright Tradition”

5. Hans Haacke, “Revisiting Free Exchange: The Art World After The Culture Wars,” a conversation with editors Robert Atkins and Svetlana Mintcheva.

6. Robert Atkins, “On Edge: Alternative Spaces Today”

7. Andre Schiffrin, “Market Censorship”

8. Wallace Kuralt, “Unfair Trade Practices in Bookselling”

9. Dee Dee Halleck, “The Military-Industrial Complex is Dead! Long Live the Military-Media-Industrial Complex!”

Section 2: The Internet

1. Introduction: Robert Atkins, “High Wire[d] Act: Balancing the Political and Technological”

2. Laurence Lessig, “Creativity in Real Space”

3. Douglas Thomas, “Hacking Culture”

4. Giselle Fahimian “How the IP Guerillas Won: ®™ark, Adbusters, Negativland, and the “Bullying Back” of Creative Freedom and Social Commentary”

5. Alexander Galloway and Eugene Thacker, “Protocol, Control, & Networks”

6. “Power, Politics, New Technology and Memory in the Age of the Internet,” Svetlana Mintcheva in conversation with Antoni Muntadas

Section 3: Protecting Children

1. Introduction: Svetlana Mintcheva, “Protection or Politics? The Use and Abuse of Children”

2. Marjorie Heins, “Media Effects”

3. “Taboos, Trust and Titillation: Teens Talk About Censorship,” a roundtable discussion with high school- and college students, moderated by Stephanie Elizondo Griest and Svetlana Mintcheva.

4. Seth Killian, “Violent Video Game Players Mysteriously Avoid Killing Selves, Others”

5. Judith Levine, “Censorship, The Sexual Media and the Ambivalence of Knowing”

6. “Not a Pretty Picture: Four Photographers Talk About Their Experiences with Censorship, ‘Child Pornography’ and the Law”:

• Marian Rubin,

• Jackie Livingston,

• Marilyn Zimmerman

• Betsy Schneider.

7. Amy Adler, “Child Pornography Law and the Proliferation of the Sexualized Child”

8. Mick Wilson, “Invasion of the Kiddyfiddlers”

Section 4: Cultural Diversity & Hate Speech

1. Introduction: Svetlana Mintcheva, “When Words and Images Cause Pain: the Price of Free Speech”

2. Randall Kennedy, “Pitfalls in Fighting Nigger”

3. Michael Harris and Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Past is a Prologue but is Parody and Pastiche Progress?” a conversation moderated by Karen C. C. Dalton.

4. “Beyond Good and Evil,” Editors Robert Atkins and Svetlana Mintcheva in conversation with Norman Kleeblatt and Joanna Lindenbaum, about the exhibition Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery/Recent Art

5. John Leanos, “My Memorial to Patrick Tillman”

6. Diane Ravitch, “The New Meaning of Bias”

Section 5: Self-Censorship

1. Introduction: Svetlana Mintcheva, “The Censor Within”

2. “To Discern, to Discriminate and to Decide: A Conversation about Censorship and Institutions,” with Tom Finkelpearl, Director of the Queens Museum of Art, Thomas Sokolowski, Director of The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and editors Svetlana Mintcheva and Robert Atkins

3. J.M. Coetzee, “Taking Offense”

4. Judy Blume, “Censorship: a Personal View”

5. The Ubiquitous Censor: Artists and Writers on Self Censorship

• Leeza Ahmadi

• Guillermo Gómez-Peùa

• Glenn Ligon

• Barbara Pollack

• Carolee Schneemann

• Betty Shamieh

6. Janice Lieberman, “A Psychoanalyst’s Perspective on Artists and Censorship”

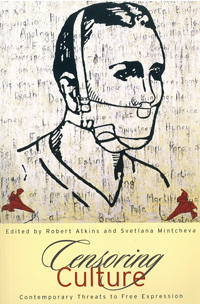

Introduction

Censorship has always been a dirty word. (It derives from the Latin for census taker or tax collector; designating one of the most reviled citizens of the Roman Empire.) In the legal sense, censorship is the governmental suppression of speech because of the viewpoint expressed in it. In a broader sense, it refers to private institutions or individuals doing the same thing, suppressing content they find undesirable. The difference is that the former is prohibited by the First Amendment and the latter is not. Regardless of its legality, however, censorship is unpopular. The classic image of the censor depicts a narrow-minded and prudish bureaucrat from a totalitarian regime, blind to the transcendent flights of the imagination we call art, burnishing his red pen or his stamp and inkpad with perverse pleasure. This portrayal renders the censor as the very opposite of the creative artist. But censorship often operates more subtly than that, sometimes disguised as a moral imperative, at other times presented as an inevitable result of the impartial logic of the free market. No matter what the camouflage is, however, the result is the same: the range of what we can say, see, hear, think, and even imagine is narrowed.

Of the many debates about censorship in recent memory, not one has opened with a public official saying, “Let’s censor this.” On the contrary, the standard initial talking point is “This is not censorship, we do not censor,” followed by: “We need to be sensitive to community standards;” “We need to protect children who might see this,” “We can’t spend taxpayers’ money to support work that might offend;” or “We don’t consider this censorship at all, because you are free to exhibit your work elsewhere.” The censor’s current disguises of choice are the moral imperatives of “protecting children” and of exercising “respect for religious and cultural beliefs and sensitivities.” Both, in themselves, laudable objectives and, for this reason, perfect disguises for other, less savory motives.

Before something is censored, however, it must be produced and distributed, that is, attain some visibility. A discussion of censorship that only takes into account attempts to repress existing works, misses all those works that never came to life: Perhaps, because this novel didn’t seem sufficiently commercial, there was no chance of it being published or, perhaps, because that play might have offended somebody, the playwright censored himself at the outset and decided not to write it at all.

Censoring Culture expands the notion of censorship beyond the acts of removing a photograph from an exhibition or canceling a performance to include a much larger field of social conditions and practices that prevent artists’ works of all kinds from reaching audiences or, even, from being produced. The narrow collecting purview of a museum, for instance, might be irremediably problematic for contemporary painters if no museum in their country collected work by living artists. Or, consider the modestly successful, mid-career writer: Although her books have earned back her publisher’s investments, at certain houses, she may be ignored, given the all-consuming editorial quest for the Big Book. Finally, the temporal extension of intellectual property rights practically prohibits American artists from working with images from the cultural vernacular of their day, such as Barbie or Batman and Robin. In few of these cases did somebody consciously make a decision in order to frustrate or limit artists’ opportunities for expression. Nonetheless, within these situations, we see constraints on creativity and access to needed cultural materials. Such limitations both impoverish our culture and undermine our shared myth of freedom.

The central goal of Censoring Culture is the expansion of the very notion of censorship. The specific disguises, mechanisms, and systemic factors we invoke and which are discussed within the book—with the exception of the Internet—all predate the culture wars of the 1980s and 90s. We make no claim to identifying entirely new phenomena. The fact that a phenomenon has been recognized, however, does not mean that it is sufficiently, or well, explored.

The dire effects on free expression of corporate consolidation, especially in the media for example, have been noted. The self-defeating extremes of political correctness have been subject to harsh criticism. (They are often dismissed as the whining of political “others.”) The subtle but powerful force of self-censorship, on the other hand, remains little discussed or understood—although its ubiquity in totalitarian societies and familiarity to artists and writers in every society is hardly a secret.