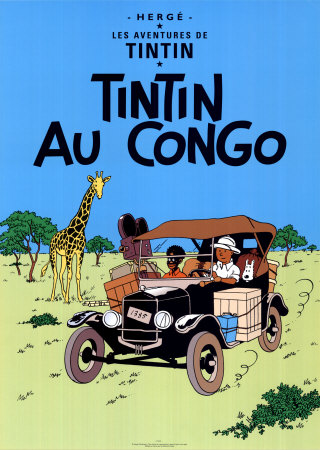

The cover of Hergé's book "Tintin Au Congo"

The Brooklyn Public Library trusts you to form your own opinions about any controversial and provocative content that you would find in Beloved, Hard Candy or Mein Kampf. However, apparently they feel the need to protect you from racially insensitive material in the cartoon from almost 80 years ago TinTin Au Congo.

The NYTimes today reports that the Brooklyn Public Library’s Materials Review Committee has decided to remove the book from its shelves. Chair of the committee, Christine Stenstrom does acknowledge that the book, created by Hergé in 1929, “is of historic interest” and therefore “it will be added to the Hunt Collection of Children’s Literalure, which is located in the Central Library. This is a special collection of historic children’s literature that is available for viewing by appointment only.”

As the Times notes, the Brooklyn Library has actually had a good track record of keeping controversial material. In their recent record of responses to requests to reconsider library materials, this is the only book they chose to remove from shelves because the review panel found it “racially offensive.”

I have no doubt the cartoon is racially offensive (you can see by the cover). But will people find it more so than Mein Kampf several other books, films, cartoons and artwork that would be readily available in Brooklyn Library? What happens when someone complains about Disney’s 1941 movie Dumbo because of its racially offensive character Jim Crow? What about Twain’s classic novel Huckleberry Finn which is regularly challenged because it contains the racially offensive word “nigger”? Can we be trusted to consider those materials in their artistic and historical contexts, if not with “Tintin Au Congo”?

Brooklyn Library has responded respectfully and responsibly to every other challenge of this nature. In their letters, to complaintants, they have often quoted the ALA’s Diversity in Collection Development which states, “librarians have a professional responsibility to be inclusive, not exclusive…. Access to materials legally obtainable should be assured to the user and policies should not unjustly exclude materials even if offensive to the librarian or user.”

So what makes this book any different – so dangerous that it needs to be locked up? And now that they’ve removed it, what’s next? And furthermore, how will they defend any future decisions to keep controversial materials now that they’ve set this disarming precedent?