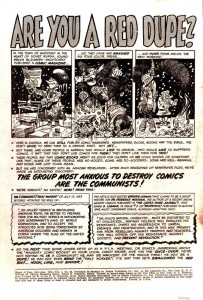

What a difference 60 years can make. On this day, in 1954, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency was closing out a second day of hearings. These two days would prove a pivotal period in comics history, leading to decades of self-censorship that almost destroyed the industry.

Better described as a kangaroo court that threw aside the First Amendment rights of an entire industry as a result of faulty “scientific” evidence, the April 21 – 22, 1954, Senate hearings were led by Senator Estes Kefauver and featured star witness Fredric Wertham. Wertham frequently targeted Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, crime, and horror comics, using pseudoscience to claim that comics caused juvenile delinquency, homosexuality (then considered a mental illness), violent crime, and more. Wertham’s April 1954 testimony against comics was no less damning:

Mr. Chairman, I am just a doctor. I can’t tell what the remedy is. I can only say that in my opinion this is a public-health problem. I think it ought to be possible to determine once and for all what is in these comic books and I think it ought to be possible to keep the children under 15 from seeing them displayed to them and preventing these being sold directly to children.

In other words, I think something should be done to see that the children can’t get them. You see, if a father wants to go to a store and says, “I have a little boy of seven. He doesn’t know how to rape a girl; he doesn’t know how to rob a store. Please sell me one of the comic books,” let the man sell him one, but I don’t think the boy should be able to go see this rape on the cover and buy the comic book. I think from the public-health point of view something might be done now, Mr. Chairman…

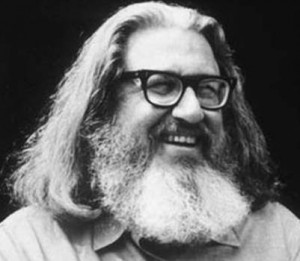

Although the cards were stacked against him, Gaines came out swinging. In the first moments of his testimony, he declared:

I was the first publisher in these United States to publish horror comics. I am responsible, I started them. Some may not like them. That is a matter of personal taste. It would be just as difficult to explain the harmless thrill of a horror story to a Dr. Wertham as it would be to explain the sublimity of love to a frigid old maid.

Gaines didn’t stop there:

Entertaining reading has never harmed anyone. Men of good will, free men should be very grateful for one sentence in the statement made by Federal Judge John M. Woolsey when he lifted the ban on Ulysses. Judge Woolsey said, “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” May I repeat, he said, “It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned.” Our American children are for the most part normal children. They are bright children, but those who want to prohibit comic magazines seem to see dirty, sneaky, perverted monsters who use the comics as a blueprint for action. Perverted little monsters are few and far between. They don’t read comics. The chances are most of them are in schools for retarded children.

What are we afraid of? Are we afraid of our own children? Do we forget that they are citizens, too, and entitled to select what to read or do? Do we think our children are so evil, so simple minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery? Jimmy Walker once remarked that he never knew a girl to be ruined by a book. Nobody has ever been ruined by a comic.

As has already been pointed out by previous testimony, a little healthy, normal child has never been made worse for reading comic magazines. The basic personality of a child is established before he reaches the age of comic-book reading. I don’t believe anything that has ever been written can make a child overaggressive or delinquent. The roots of such characteristics are much deeper. The truth is that delinquency is the product of real environment, in which the child lives and not of the fiction he reads.

There are many problems that reach our children today. They are tied up with insecurity. No pill can cure them. No law will legislate them out of being. The problems are economic and social and they are complex. Our people need understanding; they need to have affection, decent homes, decent food. Do the comics encourage delinquency? Dr. David Abrahamsen has written: “Comic books do not lead into crime, although they have been widely blamed for it. I find comic books many times helpful for children in that through them they can get rid of many of their aggressions and harmful fantasies. I can never remember having seen one boy or girl who has committed a crime or who became neurotic or psychotic because he or she read comic books.”

Needless to say, Gaines’s stance did not sit well with the senators present, nor was it compatible with the public mood of the era (an anti-comics sentiment that was largely fostered by Wertham himself). Gaines unwisely continued to confront the lawmakers present, and Senator Kefauver badgered Gaines into several missteps:

Chief Counsel Herbert Beaser: Let me get the limits as far as what you put into your magazine. Is the sole test of what you would put into your magazine whether it sells? Is there any limit you can think of that you would not put in a magazine because you thought a child should not see or read about it?

Bill Gaines: No, I wouldn’t say that there is any limit for the reason you outlined. My only limits are the bounds of good taste, what I consider good taste.

Beaser: Then you think a child cannot in any way, in any way, shape, or manner, be hurt by anything that a child reads or sees?

Gaines: I don’t believe so.

Beaser: There would be no limit actually to what you put in the magazines?

Gaines: Only within the bounds of good taste.

Beaser: Your own good taste and saleability?

Gaines: Yes.

Senator Estes Kefauver: Here is your May 22 issue. [Kefauver is mistakenly referring to Crime Suspenstories #22, cover date May.] This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

Gaines: Yes sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it, and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

Kefauver: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

Gaines: A little.

Kefauver: Here is blood on the axe. I think most adults are shocked by that.

As for Gaines himself, the hearings changed his course forever: Gaines’ deep resentment of Wertham’s assertions and the impact of the Senate hearings colored his attitudes towards publishing. To escape the regulation of the Comics Code (and the dwindling comics sales he saw after the code was enacted), Gaines founded Mad magazine, encouraging cartoonists to lampoon authority. The magazine became a powerful influence on cartoonists and activists in the years to come.

Today, the Comics Code is no more. You’d think that comics could proliferate safely, and our freedom to read would be assured, but CBLDF continues to exist for a reason. If comics hadn’t been attacked so vigorously in 1954, would CBLDF still need to fight on their behalf? While we’re unlikely to see two days of anti-comics hearings take place on the Senate floor today, comics are still targeted by would-be censors. Until recently, comics were generally considered a second-class literature, a legacy of Wertham and Kefauver’s 1954 crusade against them. We can only hope that as this crusade fades with time, CBLDF won’t need to continue defending comics 60 years from now.

We need your help to keep fighting for the right to read! Help support CBLDF’s important First Amendment work by visiting the Rewards Zone, making a donation, or becoming a member of CBLDF!

For an in depth examination of the history of comics censorship, check out the following series from CBLDF:

History of Comics Censorship, Part 1: From comic book burnings to the arrival of the Comics Code.

History of Comics Censorship, Part 2: From Mad Magazine and the birth of Marvel Comics through the Underground Comix era, the Zap #4 obscenity trial, the revision of the Comics Code and the arrival of the obscenity test.

History of Comics Censorship, Part 3: From the birth of the comics specialty market to the establishment of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

History of Comics Censorship, Part 4: Legal attacks on artists, including Paul Mavrides, Mike Diana, and the creators of DC Comics’ Jonah Hex: Rider of the Worm & Such.

History of Comics Censorship, Part 5: Legal attacks on retailers and publishers, including Planet Comics’ obscenity bust for horror comics; Texas’ prosecution of Jesus Castillo for manga; Top Shelf’s dispute with U.S. Customs, and Georgia’s battle with a retailer over a depiction of Picasso.

History of Comics Censorship, Part 6: Library bans and prosecutions of readers over manga.