Maybe not.

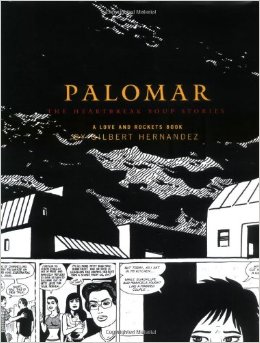

The book in question is Palomar, a critically-acclaimed graphic novel by Gilbert Hernandez. The parent who complained — and promptly took her complaint to the local press — called it "child pornography" and said it glorified sex and abuse, among other things. A school district spokesperson seemed to agree, telling the local newscast the book was "clearly inappropriate." This was not in keeping with the district’s policies, which advise that library materials under reconsideration should be “treated objectively, unemotionally, and as a routine matter.”

On March 9, NCAC's Kids Right to Read Project sent a letter to Rio Rancho Superintendent V. Sue Cleveland, urging the book be kept on the shelves, and arguing that the lurid accusations of "child pornography" were inaccurate.

A review committee met in March and voted to keep Palomar in the library. But the book, it turns out, was removed from the collection in violation of district policy, and still has not been returned.

Reporter Rita Daniels of radio station KUNM decided to file a New Mexico open records request to find out more about how the school handled the case. As she reported on July 14, the parent filed a formal challenge, as per school policy. But the school had already removed Palomar from the library after she made an informal complaint. And the documents unearthed by Daniels show that some officials were unaware of the most basic aspects of responding to challenges of library books.

Shortly after the parent made her objections known, school librarian Brenna McCandless wrote an email to the school’s principal saying Palomar's content "is quite adult," and added that "I've already removed it from the collection because it’s definitely not something we should have." She also wrote that the library was checking for other potentially objectionable material: "We’re currently going through the graphic novel collection by hand just to make sure nothing else has slipped through the cracks."

The school's vice principal, Sherri Carver seemed unsure as to why there needed to be any formal review process, since to her there was "no question the book needs to be removed from circulation." The documents show that one administrator — assistant superintendent of the school district, Carl Leppelman — explained that the school had not followed proper procedures.

The school eventually formed a committee to review the challenge; the emails inviting committee participation noted that the meeting was not likely to take more than 30 minutes. That committee voted to keep the book in the library. But Palomar never made it back to the shelves; if and when it does, Roberts reports, it will require parental approval to be checked out: "No other novel at the school has that caveat attached to it… and for now Palomar is still sitting in the district superintendent’s office four months after the vote."

The parent has said she’s appealed to the superintendent to overturn the decision and purge the book from circulation completely, and unfortunately, it is pretty clear where school officials stand on the question. Assistant principal Carver, in a March 17 email, states that she believes the superintendent "may overturn the committee's decision." The school principal Richard Von Ancken responds: "I hope she does."