An art installation, sponsored by the new Czeck EU Presidency, and displayed in the European Council building in Brussels has become a litmus test for EU sensitivities. The conceptual artist David ?erný was commisssioned to invite 27 artists from EU member states to represent their country as they see it. The idea was to gather specifically personal, non-government approved and possibly critical views so as to demonstrate the EU committment to artistic freedom.

David ?erný’s installation “Entropa”

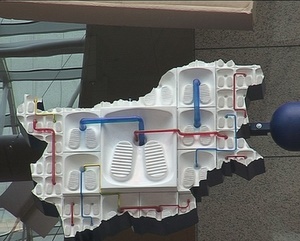

What the exhibit ended up demonstrating was that the EU committment to artistic freedom – especially that of some of its new members – is rather shaky. As to the member states’ sense of humor – it proved to be inversely proportional to a country’s status in the Union. As it happened, the government of Bulgaria, a country new to the Union and on its political as well as geographical margins, officially demanded the removal of the part of the exibin representing it as a bunch of Turkish style squat toilets linked by red and blue lines (the colors of the two leading parties). Bulgarian officials claimed that the work was “in bad taste and provoked bad associations” and protested that Bulgarian government institutions were not informed of the selection process.

All this says a lot about the Bulgarian government’s respect for opinions other than the “officially” formulated ones and reminds me (full disclosure – I grew up in Bulgaria) of socialist times when a bright flowery facade was imposed on half-finished construction whenever a Party Congress was held or high level foreign officials visited. So, no matter what mess the country is in, we are all supposed to show a proud and beautiful facade. As it turned out, however, in the Entropa installation case there was no selection process. David ?erný, instead of selecting artists from the member states, created false artist identities (brilliantly, by the way – the brochure for the installation has bios and exhibition histories that all look very real) and made all the elements in the installation himself. They are all edgily ironic and potentially offensive – some more than others – but none of them are entirely gratuitous. In fact, it is probably because it hit a nerve that the Bulgarian component was so disturbing to the country’s government. Not only are squat toilets (still easily found in Bulgaria) a reminder of its failure to become totally Europeanized, but they speak of its strained relationship to its ethnic Turks and hint at the role played by the small yet powerful political party representing them. The piece generates a wealth of other associations – none of them too complimentary, admittedly, but since when does art have to stroke national egos?

The fact that ?erný has been so successful in provoking a discussion already validates his installation. That the discussion itself is perhaps more revealing of national character and politics is something, which the Bulgarian government should take into account before puttung its foot down and insisting on censorship.

Here is a link to a petition to the Bulgarian government to stop its demands for removing the work: http://bgpetition.com/protiv_cenzurata_david_cherny/index.html

Update:

On Jan 19th a black cloth covered up the Bulgarian section of Entropa. “We have covered the part devoted to Bulgaria at the request of its foreign ministry,” declared Czech presidency spokesman Jan Vytopil.

By succeeding in its calls for censorship the Bulgarian government shot itself (or, more unfortunately, its country) in the foot twice – once by having the black cover remind all of Europe that Bulgaria still values censorship above free speech and then again by making, in effect, the toilet piece the most memorable one in the installation and giving it a legitimacy David ?erný never intended.