In March of 2023 Michelle Hartney’s collaborative mixed media installation work titled Unplanned Parenthood was met with censorship in Idaho. In March 2025, calls for censoring the work nearly succeeded again in Illinois. Hartney met with ACAP Director Elizabeth Larison and shared more about the project, and why she believes some audiences are afraid of its powerful message.

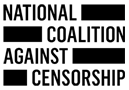

He Scorns Me Now and Instead of Helping He is Positively Cruel, 2023

Porcelain, rosary beads, fabric from a vintage wedding dress, thread

Can you tell us a little bit about Unplanned Parenthood? Why were you driven to make this work?

Unplanned Parenthood is a collaborative art installation that explores what life was like, especially for mothers, when birth control and abortion were illegal in the United States. I was driven to create this project after the April 2022 Supreme Court leak occurred, revealing the impending overturn of Roe v. Wade and the loss of abortion rights for many people across the country.

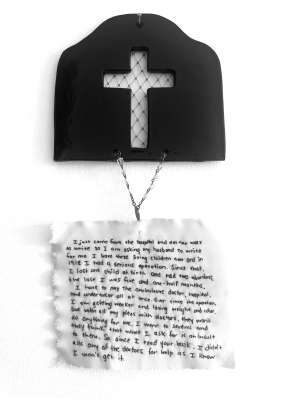

I built the project around letters written to Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, who received over 250,000 pieces of written correspondence in the 1920s—mostly from mothers begging for information about birth control. The letters are heartbreaking: many women wrote that they would rather die than have another baby. Some lived in extreme poverty, suffered physical abuse from their husbands, or had husbands who abused their children. Many of them wrote Sanger, expressing how they didn’t want to have to bring another child into those living circumstances. A lot of them also faced severe health issues that made it dangerous or even deadly for them to have to go through another pregnancy. Their words were so desperate and powerful, and the sheer volume of letters written to Sanger during this time made me want to amplify their voices to make sure that they weren’t forgotten.

I also wanted to do this project because many white feminists, and even Planned Parenthood, tend to ignore Sanger’s history of support for white supremacist movements. She spoke to the KKK, supported eugenics for a period of time, and supported government-sanctioned sterilization of people considered to be unfit to have children. I wanted to communicate these realities alongside the project just so people could see the full picture.

To bring the project to life, I put out a call for public participation. The first phase of the project involved volunteers hand-copying letters that I had selected. They would just email me, I’d send them a letter, and then they would email me back the handwritten version.

In the second phase of the project, I printed the handwriting onto fabric, which came from wedding dresses I got from eBay. Then I worked with volunteers to embroider the handwritten letters onto the fabric. That part of the project really took off when Roe v. Wade was officially overturned. Many participants found the work to be healing, because so many people were upset and wanted to do something beyond protesting or donating to Planned Parenthood. As a result, sewing circles emerged across the United States: taking place on college campuses, in museums, and in galleries. At a couple of these circles, representatives from the ACLU spoke to participants because this was right when Roe fell, and people didn’t know how it would affect abortion access within their respective states.

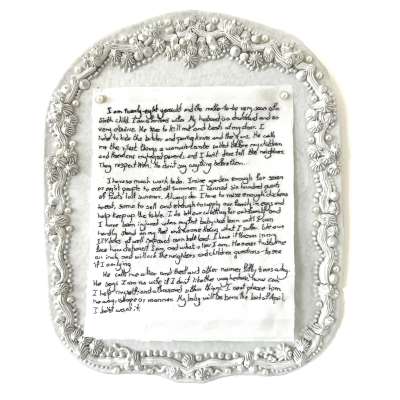

Once I had enough embroidered pieces, I created the final iteration: an installation made of porcelain backings layered with symbolic materials framing the embroidered letters. I think my favorite materials are vintage meat hooks, which I use to pierce the fabric; I wanted something to symbolize the brutality of the patriarchy and felt like the meat hooks really communicate how people with uteruses are treated like animals, and our bodies are treated as if they are not our own. I also used other materials like fabrics that are considered feminine, such as lace, bra straps, tulle and fishnet. I also use rosary beads in a few of them, to comment on the role of religion in controlling people’s bodies.

Is the project still ongoing at this point?

The project is definitely ongoing. I still have a lot of letters that are only partially embroidered, because they have traveled through the sewing circles. So a lot of those need to be completed. My dream is that any future exhibition of this work would always incorporate a sewing circle, ensuring that the project remains an evolving, participatory experience. With over 250,000 letters, there is an ample supply of words and stories that need to be told.

How does the work discuss the complex history of Margaret Sanger?

It’s something that I require to be contextualized through exhibition wall labels. I have explored this in other works, and advocated for the importance of contextualizing art, particularly in public spaces like museums. My one rule for this project is that anytime it’s displayed or talked about, Sanger’s past, including her racism, must be addressed. I don’t want this work to be out there and for people to interpret it as an uncomplicated celebration of Sanger.

My Husband Is a Drunkard, 2023

Porcelain, faux pearls, fabric from a vintage wedding dress, thread

Can you talk a little bit about the two different times that people have censored, or attempted to censor, this work? What did people take issue with?

The first time Unplanned Parenthood was censored, it was removed along with two other artworks that were about abortion, from an exhibition called Unconditional Care at Lewis-Clark State College, in Idaho. While my project is about birth control—not abortion—one of my pieces included a letter from the 1920s in which its author, a mother, mentioned having two abortions. The college administration took issue with this, despite the fact that the author of my letter expresses a desperate desire for birth control to avoid future abortions, and she describes the financial burden of having had these two abortions. Idaho law prohibits government funding from supporting anything perceived as “promoting” abortion, and this was used as justification to remove my work. To be clear, I don’t think my work, nor the work of the other censored artists, promotes abortion. Lydia Nobles’ video interviews are informative and simply presented lived stories of real people; Katrina Majkut’s works are embroideries of abortion pills. The college cited that law as a reason to silence us, and it’s the same law that’s preventing women’s studies professors in Idaho from discussing abortion in class.

The second time I was censored was this year at the International Museum of Surgical Science (IMSS) in Illinois, which is affiliated with the International College of Surgeons (ICS). A solo show of the project had been up for about 3 months and no one had a problem with it. But the first week of January, I guess somebody saw it, which inspired an article that was then published on a conservative website. The article condemns my use of a rosary in one of the pieces, calling my work “blasphemous.” That article went viral and people began calling the museum and threatening its employees. In response, the director of the International College of Surgeons instructed the IMSS director and curator to take down the entire exhibition. At first, the museum director simply told me about the article, which I dismissed because I’m used to such reactions, but a few hours later, she informed me that I needed to come and remove my work immediately. Normally at museums, artists don’t install or deinstall their own work, but the IMSS has a small team, and my project is very fragile, so, in preparation for the opening, I installed the whole show. I actually broke a piece during install so I think the fragility of some of the work ended up benefiting me later on, I’m not sure that the staff would have removed my work without my involvement. But, I refused to take the work down, saying that I would go to the press and contact lawyers, as I have been through this before.

And I’m grateful that I have been through this process before, because I contacted the National Coalition Against Censorship, the ACLU, and FIRE—and you, Elizabeth, responded to me immediately, and ended up offering support to IMSS staff in favor of retaining the exhibition as planned. I felt like I was shooting out a bat signal and NCAC was so on it, and I’m so grateful for that. The director of ICS ultimately decided to keep the show up.

So yes, while the work was censored for seemingly different reasons, its references to abortion and the control of people’s bodies and voices are at the root of it.

What’s fascinating to me, is that your use of the rosary constitutes a materially very small portion of work, and pretty easy to miss. Compared to the hundreds of square inches of ceramic, embroidered fabric, and other elements— you use maybe 5-6 inches of rosary beads. And yet it clearly became the focal point for controversy in Chicago.

I don’t remember exactly which pieces were on view at the IMSS, but I think there were only two, maybe three works that had rosary beads—and those that used the rosary maybe had an inch or two each. In one, I did include a crucifix, but it’s still a really small element of the project.

I wanted to use something that was provocative, and clearly that material got some attention. I think the reason people target these small details is because they know the real power in this work is in the stories and words of these mothers. Their letters are devastating. These women were desperately pleading for information, for control over their own bodies. And to read those letters and not feel some sort of pain on behalf of those mothers, you just have to have a stone cold heart. And I think people know that, so they have to attack the work in some other way. I think the author of the article, or whoever tipped her off, saw the word “abortion” or the image of a rosary bead and immediately tried to shut it down.

I’m certain that some of the people criticizing my work and calling the museum never even read any of the letters or my statement. I say this because the first thing a lot of people were trolling me about was that Sanger was a racist… which, as I noted, I take care to address in my project.

It’s interesting that in Idaho, your work was censored because a state college claimed they were worried about complying with a vague, broadly-worded state law. So, if we take that claim at face value, you have fear driving censorship. And then in Illinois, there’s this online publication that seems more focused on stirring moral outrage than it is on any kind of meaningful engagement or criticism. That makes me think it’s likely that many of the people harassing the museum workers weren’t even from Chicago, or had no real understanding of the exhibition beyond a couple of cherry-picked images they saw online.

It’s funny because you’re never supposed to read the comments of articles like this, but I read them from that article just so I could just learn where critics were coming from, ideologically. There was a lot of emphasis on how irate “the Chicago Catholic community” was, but in reality, we are talking about two people complaining in the comments section. It’s not a widely visited museum. I’ve lived in Chicago my whole life and I’d only heard of it in recent years. It’s just interesting to see how it takes just a few individuals to rally this invisible army of conservatives who will just attack any issue that they find threatening.

I’ve Had Three Children Taken Away From Me, 2023

Porcelain, bra strap, vintage meat hook, fabric from a vintage wedding dress, thread

What was your first inkling that there was trouble afoot in the Idaho exhibition?

In Idaho, Katrina Majkut, the guest curator who also ended up having her own work censored, called me maybe a week before the show and mentioned that the college had concerns surrounding the name of one of the artist collectives that had work in the show: Gays Against Guns. There was administrative concern that the word “gay” would not be permissible or be supported by one of the college’s PR team. They ended up using the group’s acronym, GAG, in the press release to bypass this concern and avoid any road blocks (since it was commonly used by the group anyway), but used the group’s full name in all gallery texts. I never really thought that would foreshadow my own work being censored, but in retrospect I think that this was a yellow flag, signaling a kind of discomfort with the exhibition. It was either the day before or the day of the opening when Katrina called me and said, “it’s going down,” in reference to my work.

Are these the only times that this work has been shown? Has it been shown in other instances without issue?

It’s shown several other times and places, and I haven’t faced censorship in any other instances.

After the work was censored in Idaho, it was invited to be part of an existing show about abortion here in Chicago at Weinberg Newton Gallery (the gallery is now closed). They only showed art about social issues, and weren’t afraid of controversy or challenging work. After my work was censored in Idaho, I reached out to the curator and she immediately invited not just my work, but Lydia’s and Katrina’s censored work to join the exhibition on view, as a reflection of the urgent circumstances we found ourselves in.

A portion of the series was also shown at a university in Kansas City, Missouri, as part of an exhibition about labor. I received several emails of appreciation from people who saw my work there. One woman wrote, “I saw your work and it broke my heart, and I donated to Planned Parenthood.” I also held a sewing circle at Lump Gallery in North Carolina, and I also held a sewing circle and displayed prints at a university in Connecticut.

How have efforts to censor your work affected how you think about the project? Have they impacted how you will continue to present it in the future?

The fact that this project has been targeted more than once underscores for me that these mothers’ words are hitting people in their hearts. It’s hard not to feel empathy for these poor mothers who lived when abortion and birth control were illegal.

These responses also encourage me. They tell me that the project is doing what it was meant to do. Because when I first read these letters, they upset me so much that I needed to create something from them. I believe that words alone have power, but I also believe that the use of materials like the meat hooks, the bra straps, the lingerie, and the rosary beads build on that meaning.

As far as showing the work in the future, honestly, I’m still figuring it out. The Trump administration is new and scary. But I also have a lot of connections with feminist artists and some curators who focus on bodily autonomy who are determined to find ways to continue that work. The thing is that now, even curators and institutions are starting to refuse works of art before a controversy can even happen. I don’t know if there’s a word for that… pre-censorship?

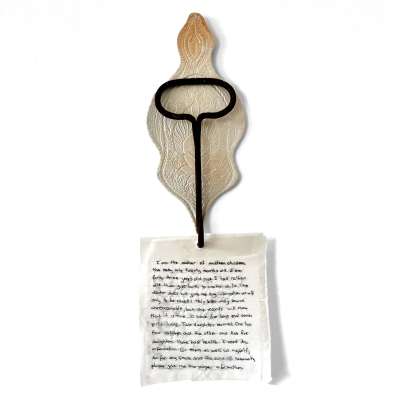

I am The Mother of Nineteen Children, 2023

Porcelain, vintage meat hook, fabric from a vintage wedding dress, thread

Yes, that’s a term that I’ve used sometimes. I certainly can’t say that I came up with it, but it’s a type of self censorship that happens during the decision making, creative, and/or curatorial process.

Yes, this is happening right now, as my work has been censored, yet again.

Unconditional Care, the exhibition that was censored in Idaho, was supposed to be shown at the Pelham Center in New York. Then, the same day the IMSS asked me to take down my work in response to online complaints, Katrina, the curator of Unconditional Care, emailed me to say that the Pelham Center was no longer taking on that show.

The decision was driven by concerns regarding the murder of the United Healthcare CEO and the broader political climate. I think it’s important to emphasize that this was in New York and before Trump was even inaugurated, before the threats to federal funding, before a lot of what we’re seeing now.

Institutions are caving, and I think curators and directors of arts institutions are getting a lot of the blame for it. They’re the public faces of these institutions, so when censorship happens, they’re the ones who are blamed. But most of the time I feel like it’s not a curatorial decision, it’s the institution censoring and controlling what gets shown. That’s what happened in Idaho. Katrina, because she was the curator, was worried that she was going to be charged with a felony, and the onsite curator employed by the museum was also fearful of getting arrested! The No Public Funds for Abortion Act is such a vague law, and we were all so confused about its implications.

Institutional self-censorship, curatorial self-censorship are both abundant right now, but also very hard to track because if something was never officially selected, and/or it was never publicized that it would be on view, it’s hard to prove it was under advanced consideration.

In terms of pre-censorship, I know that my career has been hurt because of the type of art I create. I don’t know what my career would have looked like if I painted landscapes, but I think it would have been really different. Even before, maybe in 2019, I was supposed to have some of my work in a show about motherhood at Indiana University in Bloomington, but they cancelled the opening because one person threatened to protest, or something really weak like that.

I was also supposed to do a residency with the Kinsey Institute and the residency had nothing to do with themes of abortion. It was a residency about exploring themes of obstetric abuse and childbirth. But they were so worried that my involvement would somehow be risky for Kinsey’s funding, that it got canceled. And this was all before the creation of Unplanned Parenthood.

I Would Rather Die Than Have Another as We Cannot Afford the Ones We Have, 2023

Porcelain, jewelry findings, fabric from a vintage wedding dress, thread

Is there anything else you want to add, to round out our discussion?

I think that people who are censoring art, banning books, and attacking journalists need to face the truth, and live in the truth, even if they don’t agree with it. Art really holds up a mirror to reality, and those who want to silence artists, poets, musicians, and journalists, are really just trying to suffocate it. But you can’t avoid the truth forever.

I think that right now we are living in this “post-truth” world where conservatives don’t have any attachment to truth anymore, and it’s so dangerous and damaging. It’s harder to tell what’s real. And that’s how you create a fascist society. I think we just really desperately need to hold on to the truth as much as we can.

Agreed. Efforts to suppress works like Unplanned Parenthood—works that draw from history and people’s lived experiences—are an attempt to hide the truths of hundreds of thousands people, censor their existence, and deny their humanity.

Thank you so much, Michelle.