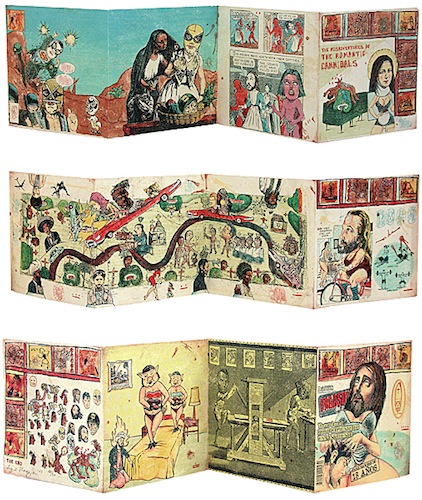

What began as a heated protest over Enrique Chagoya’s artwork at the Loveland Museum in Colorado has ended in vandalism. A disgruntled woman ripped into Chagoya’s controversial lithograph “The Misadventures of the Romantic Cannibals” after she busted the artwork’s plexiglass case with a crowbar. City council members, religious groups and individuals had hoped that the public pressure caused by the artwor’s racy religious content would get Chagoya’s piece yanked from the government-funded museum. Part of the lithograph appears to depict a Jesus Christ face on a female body receiving oral sex. The Loveland City Council met on Tuesday to discuss the issue, ultimately deciding not to intervene.

NCAC sent a letter to the City Council cautioning that if public officials intervene to suppress Chagoya’s work because they dislike the ideas expressed in it, they are likely to be found in violation of the First Amendment. The letter reminds councilors of a 1999 case where former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani pressured the Brooklyn Museum of Art to remove an “offensive” work from its “Sensation” exhibit. In that case, a federal district court ruled that Giuliani’s attempt violated the First Amendment.

NCAC writes:

Confronted with a forcefully expressed viewpoint that stands in opposition to their deeply held beliefs, people often react emotionally by being offended. In accordance with the U.S. Constitution, however, those who disagree are free to express their outrage, but cannot impose their viewpoint on everybody else. There are many ways to express disagreement with the ideas expressed in an artwork that do not entail going against the founding principles of this country: the separation of church and state and the right to free speech.

In Loveland, an offended party indeed expressed her outrage, but through means unacceptable in a civilized society: i.e. by destroying the work

Vandalism of artwork that is a subject of controversy is not new. (Artwork has also been defaced and attacked for other reasons, but that is outside the scope of today’s discussion.)

In 2007, vandals destroyed seven photographs by Andres Serrano hanging in an art gallery in Southern Sweden. Apparently, they brought along someone to videotape the attack. The video, annotated with commentary and set to a heavy metal soundtrack, appeared on YouTube. The show consisted of photographs, made in 1995 and 1996, of various sex acts, including a depiction of a naked woman fondling a stallion. It was divided into two rooms. One had white walls, the other black. The vandals went to the black room, where (show curator Viveca) Ohlsson said the photographs were a bit racier. The vandals, believed to be part of a local neo-Nazi organization, screamed, “We don’t support this!” as they destroyed the photographs. The video describes the vandals as “national socialists.”

In 2004, Israeli Ambassador Zvi Mazel was attending the opening of an exhibition at the Museum of Antiquities in Stockholm entitled “Making Differences,” which was a part of an international conference on genocide hosted by the Swedish government. Mazel flew into a fit of rage and demanded that one of the artworks in the show be removed. The piece — an installation by Israeli-born artist Dror Feiler and his Swedish wife Gunilla Skoeld-Feiler — is entitled “Snow White and the Madness of Truth,” and consists of a small white boat floating on a pool of red water designed to look like blood. The sail of the boat is made from a photograph of Palestinian suicide bomber Hanadi Jaradat, who killed herself and 19 Israelis at a restaurant in Haifa, Israel. The museum refused to remove the work, at which point Mazel pushed a spotlight into the water, causing the installation to short circuit. He was subsequently escorted from the building.

In 1999, Dennis Heiner, a 72-year-old Christian was incensed by Chris Ofili’s “The Holy Virgin Mary,” exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum of Art as part of the “Sensation” show. Heiner, a retired English teacher, feigned sickness to lean against a wall without attracting the suspicion of a guard, then ducked behind the plexiglass, took out a plastic bottle and squeezed white paint in a broad stroke across the face and body of the Madonna image. Then he smeared the paint over the head and bust of the painting, effectively obscuring the figure from view. When asked by one of the security staff “Why did you do it?” he quietly replied: “It’s blasphemous.” Heiner was later charged with second-degree criminal mischief and received a conditional discharge and a $250 fine which was viewed as extremely lenient by the arts community.

During a retrospective of Andres Serrano’s work at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1997, one patron attempted to remove the work from the gallery wall, and two teenagers later attacked it with a hammer. The director of the NGV cancelled the show, allegedly out of concern for a Rembrandt exhibition that was also on display at the time.

Violence pays homage to the power of the artwork and helps to publicize it, thus working directly against the goal of the censor to suppress — if that indeed is his or her goal. Nevertheless, damage is done: to the work, to the artist’s feelings, and most of all to the public dialogue about art or politics. Violence goes against the very foundation of a civilized country where differences in opinion should be resolved through discussion and dialogue, not by guns and crowbars. And where differences cannot be resolved, we agree to disagree and tolerate the views of others rather than killing them or destroying the results of their labor.