Back in May, Apple’s rejection of Liyla and the Shadow of War thrust their App Store into the negative PR spotlight. The game, a side-scrolling adventure in which players navigate a rockst striken wasteland, was barred entry to the store’s Games section due to it’s political pointedness- the game takes inspiration from war in the Gaza strip.

The notion that an App making political commentary could not be sold on the App store was so unpopular that, after receiving pushback from both consumers and the media, Apple reversed their decision. Sadly, this process has become increasingly regular with Apple, after at least six years of similar incidents, it is arguably apparent that Apple struggles with the idea of complete free expression for their vendors in the App Store. Complaints of app censorship, games in particular, are commonplace, and the often irrational, erratic, and selective nature of these removals and rejections is concerning to say the least. Some examples of Apple’s odd app removals include:

- Rejecting a radar detector app

- Rejecting simple technical updates to games

- Rejecting political satire games

To get a clearer picture of why these seemingly nonsensical rejections took place, it may help to look at the fine print of Apples App Store Guidelines regarding “Objectionable Content”:

We will reject Apps for any content or behavior that we believe is over the line. What line, you ask? Well, as a Supreme Court Justice once said, “I’ll know it when I see it”. And we think that you will also know it when you cross it.

The quote “I’ll know it when I see it” was taken from a Supreme Court Justice, named Potter Stewart, who was speaking on obscenity prosecutions. Nevertheless, the question arises, who decides where to draw the line of obscenity for Apple?

The truth is that Apple’s review process for apps on the App store is mysterious. We don’t know anything about who makes these decisions or how they make them. In this way, Apple’s review process is in some ways similiar to that of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), independent non-government agencies which provide age ratings for films and video games respectively.

As seemingly arbitrary as our current content rating institutions are, most consumers have become accustomed to letting these dark room review boards call the shots. However, there are two key differences which make Apple’s review system more problematic than that of the MPAA and the ESRB.

As seemingly arbitrary as our current content rating institutions are, most consumers have become accustomed to letting these dark room review boards call the shots. However, there are two key differences which make Apple’s review system more problematic than that of the MPAA and the ESRB.

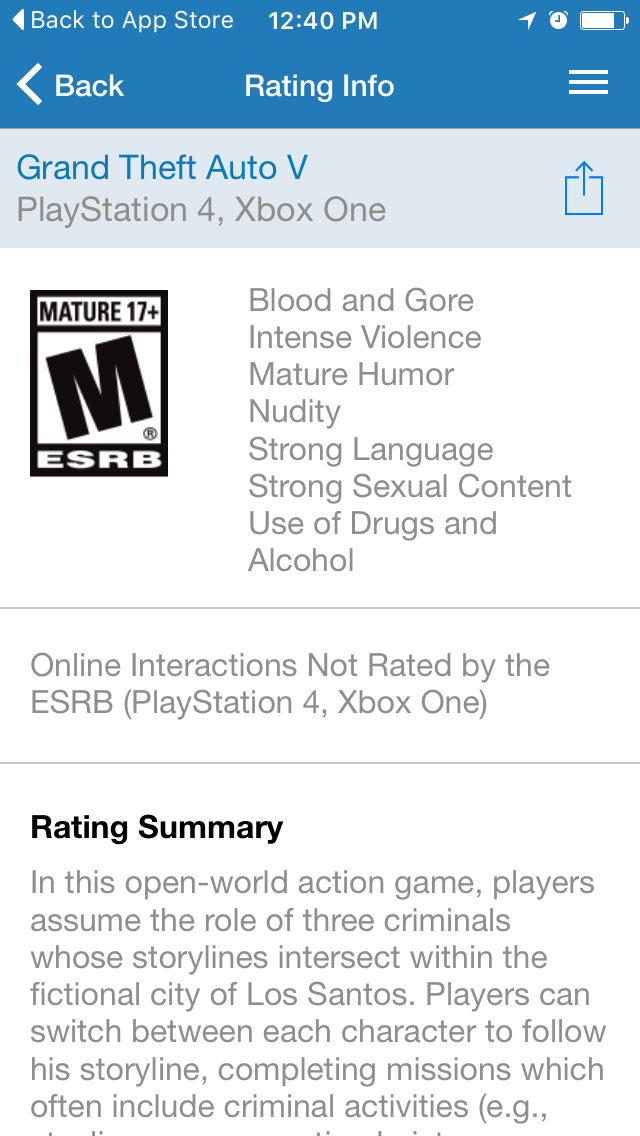

First, these other rating groups provide you with the rationale behind their decisions. The picture on the left shows how the ESRB conveniently presents all information regarding the criteria for their decision. Through the use of tags and verbal summary, consumers are provided with details about what contributed to the suggested age rating. We may not know who decided that Grand Theft Auto should be for mature audiences only, but we at least know the basis for the decision. The inconsistency in which Apple’s guidelines are followed raises serious questions of censorship of certain narratives.

For example, personal political leanings of Apple employees might explain why they rejected a weapon manufacturing game and approved a game that lets you control a bird taking a dump on Donald Trump.

Second, regardless of what decision the MPAA or ESRB makes, the ultimate decision of what kind of content we buy for both ourselves and our children is left in the consumer’s hands. If you don’t agree with an MPAA or ESRB rating, you can just ignore it, assuming you’re of the appropriate age. In contrast, when Apple rejects an app, its entire consumer base is denied the opportunity to decide what content they can purchase.

Google and Android’s Approach

For the most part, other game service providers have been able to be more liberal in regards to what type of content they allow within their marketplace, as is evident by the lack of Android or Google based controversies in their individual app stores. A perfect example of this contrast can be found in the journey of Smuggle Truck, a game which allows players to take the wheel of a truck attempting to sneak illegal immigrants into the US. Google Play accepted the game immediately. Apple rejected the title, forcing the developers to change their representation of immigrants into cuddly, colorful animals. This “new” title, Snuggle Truck, was then admitted to the App Store.

Android and Google’s success can, in some part, be attributed to their clearly defined and consistently enforced restrictions, but there’s also an element of self-regulation at play here. Android requires developers to take a survey regarding the content contained within their title, and an age rating is derived from these results.

Steam, an entirely online PC game marketplace not so different from the App Store, has taken an even more broad approach to their approval process. Instead of having an internal review board, Steam’s user base votes on which projects they want to see “Greenlit”. This model shows the most merit as it both ensures your users are not being forced to look at content they did not come to see, and also provides developers with no limits on free expression.

Consequences

To illustrate the inconsistency with which Apple filters content for sale on it’s App store, take the following case:

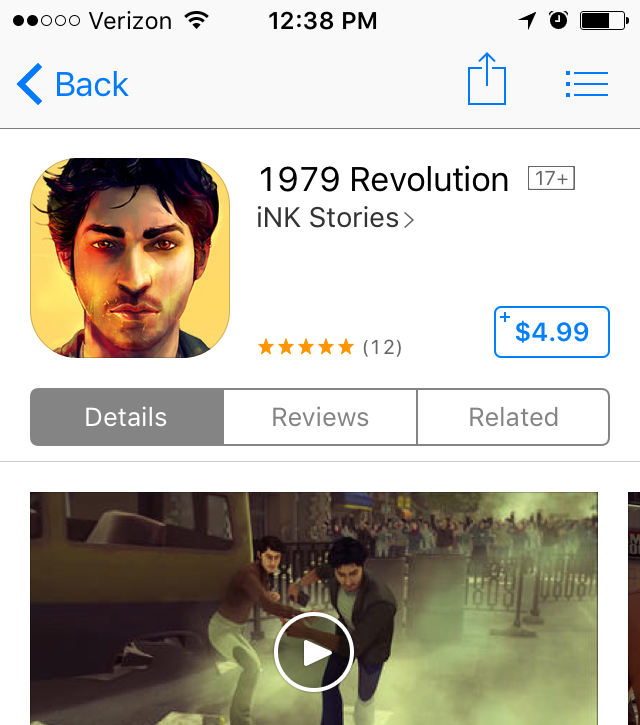

Recently, Iran blocked the sale of 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, an innovative game in which players witness a historically accurate depiction of the Iranian Revoloution through the eyes of a photographer. In an attempt to circumvent this censorship, the game developers submitted Black Friday to Apple’s App Store, knowing that the local government had no way of blocking Apple from distributing the title in their digital marketplace.

Recently, Iran blocked the sale of 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, an innovative game in which players witness a historically accurate depiction of the Iranian Revoloution through the eyes of a photographer. In an attempt to circumvent this censorship, the game developers submitted Black Friday to Apple’s App Store, knowing that the local government had no way of blocking Apple from distributing the title in their digital marketplace.

The game was accepted. However, by Apple’s own standards, this shouldn’t have happened.

Take one of Apple’s long list of guidelines:

“Enemies” with the context of a game cannot solely target a specific race, culture, real government, corporation, or any other real entity.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday features a real government (because it is historically based) and only features Iranian enemies (because it’s set in Iran).

As is evidenced by “Revolution 1979,” Apple’s well-meaning moral restrictions may end up censoring a game that could have sophisticated, and potentionally valuable narratives. It could, perhaps, have pedagogic potential.

While this time, the inconsistent nature of the App Store review process saved the day, this almost certainly will not always be the case.