The San Francisco Bay area is not the likeliest location for a censorship debate. Or one would think, at least. The area had already come up in our censorship battles lately, but more as the Magical Free Expression Castle on the Coast. San Francisco is the home of Todd Parr, author of the recently-censored The Family Book and Patricia Polacco’s embroiled In Our Mothers’ House, restricted in Utah, takes place in Berkeley. Across the Bay, however, a different picture is emerging in increasingly fine detail, as the Fremont Unified School Board once again rejected literary works from its curriculum.

For a third year, a Washington High School English teacher proposed a new text for her AP English course. For a third year, the curriculum committee, composed of teachers and administrators–all volunteers–read and approved the book for study. And for a third year, the five-member school board singled out a single book and rejected it, unanimously passing all the others.

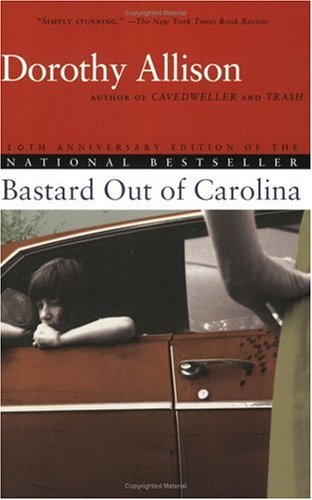

This year’s censored tome is Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, a semi-autobiographical story about a young girl coming of age in the south in the 50s and the struggles of her screwed up family life. The book was a National Book Award Finalist in 1992, it graces many college reading lists and is considered by many to be a contemporary classic. Allison is an outspoken feminist and lesbian activist who has also won numerous Lambda prizes for Best Lesbian Fiction as well as the American Library Association’s award for Gay and Lesbian Writing.

I can’t say for sure whether or not this fact came into play in Fremont, but coincidentally, last year’s veto victim was Angels in America, Tony Kushner’s award-winning play that deals with religion, homosexuality, politics and AIDS. A member of the board asserted that he had no idea these were gay authors. But when they allowed The Laramie Project to pass this year, he also expressed his hope that the “teacher teach the facts and not just the story as its portrayed” in the text. Whatever that means.

This is probably neither here nor there. What is central and of particular relevance here are the voices speaking out in favor of these books. Especially since absolutely no convincing words are being offered by would-be censors.

“Trust your teachers, trust your students,” said a parent and substitute teacher during the open comments portion of the June 27th board meeting.

A recent graduate of the district spoke as well, asserting, “I should be exposed to books that are classics but also to controversial books. I feel every book…can give you insight.”

A teacher from a high school in nearby Belmont, who has taught both texts, said Angels “teaches us what it means to be a human being in any age.”

Kyle O’Hallaren, the student member on the board (who voted to keep the book, though his vote didn’t count), told The Mercury News, “People are going to have to face stuff like that. They should be allowed to read the book.”

Board members were quoted as saying the offending books weren’t very “uplifting,” or didn’t set a good example, or portrayed so-and-so in a negative light. These were more or less the only rationales offered for the rejection. But Kyle’s words hit home: these are 17- and 18-year-old students who are supposedly being prepped for life in a world that is at equal turns beautiful, affirming, uplifting and unjust, painful and cruel. You can hope all you want that your children will live adult lives full of exclusively uplifting things, but what is more likely is that they will experience what most of us experience: a garbled hairy mishmash of the two with a delightful border of grey area.

These school board members, their supporters and like-minded parents in many other places are voicing their belief that Bad Things, Dark Things–what one speaker called “misery literature”–shouldn’t be dealt with in schools. Why is that, again? Well?

Young adults deserve more credit and more Real Talk. First of all, many of them have already been exposed to similar or worse stuff on the internet or on television, if they are lucky enough not to have dealt with them in their real lives. Some of them are already coping with heavy stuff. Some of them will soon, or have friends dealing with tough situations. Secondly, literature, especially partnered with a conversation with a sensitive teacher, can have immense power to heal and help.

Young Adult author James Dawson had a piece today about swearing in books and YA Warning Labels (a book trend story of this week, last week, every week). He makes a great point that what is scary and disturbing for one human (young or old), is popcorn-eating entertainment for another. When he was a kid, there was no YA literature; when he got old enough, he picked up Steven King and if it disturbed him, he put it down again and held off for awhile. I did the same as a young reader and I learned my own boundaries that way. And I didn’t particularly love reading about slaves being brutally flogged and their toes being severed in Night John in Friar Douglas’ 8th grade English class, but it was ultimately an immensely instructional book because, not in despite of, its graphic scenes.

Dawson writes: “Teenagers are as capable as any reader to decide what is right for them… The rise of young adult means we are able to explore ‘the darkness’ with the safety wheels on.”

No matter what censors profess, I can’t believe books about hard subjects are going to hurt anyone. And “The Darkness” doesn’t cease to exist because the Fremont School Board refuses to allow students to read about it.