This extracurricular activity remains one of the most difficult offered at school these days – anyone who has ever worked on a student paper will vouch for the work that goes into investigating and getting the scoop, the late nights editing articles, and the ethical debates over striking the balance between objectivity and thoughtfulness for the school community. Then, of course, there is the hanging threat that the hand of the school administration censor will fall on the hard-earned copy like a guillotine.

Since the Supreme Court upheld the ability of a school principal to exercise oversight of a student newspaper in the landmark student speech decision, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, achieving a model free press in the public schools is like reading the Sunday edition of the New York Times perched on scaffolding serenaded by jackhammers at a construction site. That is to say, it is not impossible.

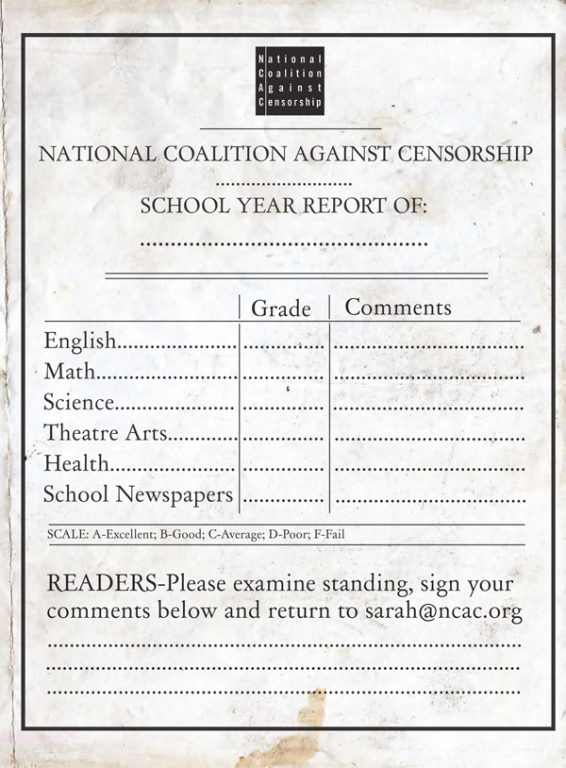

As reported by the Student Law Press Center, this year posed the usual Herculean tasks for school newspapers, magazines, and yearbooks. Some of the highlights of the low points of free speech in schools from this year:

- Just a few days ago in June, a school principal pulled 300 copies of PULP, the student magazine of Orange High School in Orange, Calif., finding a feature on tattoos unfit to distribute to the student body. The school principal told the student editors that he felt that the article glorified tattoos and gangs, the latter on account of the font used to inscribe the masthead.

- Also, earlier in June, the Challenge, the student newspaper of Thunderbird High School in Phoenix, Ariz., was not permitted to run a story about a new district policy to assess teacher performance. The students wrote a story based on the responses to a survey that was completed by teachers which questioned the effectiveness of the district’s methodology.

- In April, the well-liked faculty adviser of the Statesman of Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Ill., resigned after the school instituted a new policy giving final oversight of the school newspaper to the communications director. This change came about soon after an article on the dating habits of teenagers was published.

- In December, the superintendent of Faribault High School in Faribault, Minn., shut down the school newspaper, the Echo, because of the students had reported a story about a teacher who was under investigation by the district. The superintendent contended that by district policy, he had authority to review the story prior to publication (Read: the authority to axe the story). The superintendent made no bones about the fact that his primary concern was not the quality of the journalism – in fact, the students had collaborated with journalists from a local paper to produce the story– he claimed that he was concerned about a lawsuit. However, he then refused the students’ reasonable request to allow the school district’s attorney review the piece for legal issues, leaving us wondering about the “legitimate pedagogical interest” at stake. We might do well to remember Justice Brennan’s sad commentary in his dissent in Hazelwood – “The young men and women of Hazelwood East expected a civics lesson, but not the one the Court teaches them today.”

- Then, in January, a rather strange case of censorship arose over a senior Breanne Veney’s “memory page” for her yearbook at Cuba-Rushford Central School, in Cuba, N.Y. When the pages were submitted to the principal for review, Veney’s reference to identifying herself as “black” was crossed out and changed to “unique.” Even more insultingly, the school tried to justify its actions on the basis that Veney’s comments might offend others! Veney stood her ground and refused to allow the school to print the appalling redacted version and told the Student Press Law Center: “It bothers me because I would like to put in the memories that I have had with my friends over the years, but then again, on the other side … I don’t want to put the principal’s words in my memories.”

- Also, in January, the school district of Harrisburg High School, in Harrisburg, Ill., decided that courtesy was more important than free speech. The district board of education passed a directive forcing student journalists to use suffixes when referring to members of the faculty and administration in all news and editorial pieces. The school superintendent did not even disguise the fact that the directive was in response to an editorial criticizing the school principal.

These reported cases reveal meager respect for the rights of the student press. School officials seem to forget that while Hazelwood indicated that they may exercise control over student speech when there is a legitimate pedagogical interest, they do not have to cave into this impulse whenever a story dares to go somewhere uncomfortable. And when the case for a legitimate pedagogical interest is particularly weak, or shall we say bordering on illegitimate, then the school would serve its students well by remembering that a free press is necessary to a well-functioning democracy. Furthermore, a magazine feature on tattoos might highlight the need for a supplementary lesson during health class about risky behaviors or a discussion on fads with permanent consequences. By squashing student speech, school administrators risk blindfolding themselves from new social problems or concerns to student safety.

There is some light on the horizon that may disperse the shadows that Hazelwood has cast over the student presses. Two legislators remind us that though the Constitution may not protect student speech in schools under Hazelwood, they can through by writing these protections into new laws.

- In California, state Sen. Leland Yee bravely took on the cause of student journalists and proposed the Journalism Teacher Protection Act (Senate Bill 1370) that protected faculty from retaliation from school officials for defending student speech. In January, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed the bill into law as an amendment to California’s Education Code.

- Then, Brent Yonts, a state representative in the Kentucky General Assembly, proposed a bill that would require school boards to adopt policies granting free speech rights to school student presses. Unfortunately, the term of the assembly ended before the bill could be taken to a vote but Yonts has pledged his intention to re-file next term.

We hope that these legislators will serve as models for remembering that today’s student journalists are the torch-bearing citizens of tomorrow’s democracy. Unfortunately, all too many elected school boards often side with the curtailment of student speech to avoid controversy. On that front, it is worth taking note of the extra-credit that boosted this subject area’s grade to a respectable B+.

- Just two days ago, the Student Law Press Center reported that the school board of Lakeridge High School in Lake Oswego, Ore. refused to bow to the pressures of an anti-drug parent group who called for the school principal and faculty adviser to exercise official oversight of the student paper, the Newspacer, after the paper published a story where students discussed their drug use. The school board, instead, tweaked its student press policy so that it mirrored the language in the state’s free expression statute generally and acknowledged its high regard for the school’s student journalists.