Russell Rieger was one of five teens who sued their Long Island school district in 1976 for banning 11 books from their classrooms and school libraries. They ended up making history. The Supreme Court concluded in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico that the First Amendment limits the power of schools to ban library books.

We caught up with Rieger on the 31st anniversary of the decision to find out how he got involved in the landmark case, why he thinks people still ban books, and what it was like to meet Kurt Vonnegut, his sll-time favorite banned author.

Did you Steven Pico, Jacqueline Gold, Glenn Yarris, and Paul Sochinski realize that you’d be making history?

I still don’t view it as making history, especially since I know that book-banning still goes on.

How much did you know about your First Amendment rights as a 17-year-old high school senior?

My wife, who I was dating at the time, reminded me that we were all well aware that this was a First Amendment issue, and we took it very seriously. We were politically and socially aware and active as students. I have an older brother and sister, which made me more conscious, and my parents, especially my father, were politically engaged and encouraged us to be so, too. This was the ‘70s—and Watergate, which I watched on TV, and the Vietnam War—were still a part of our identity.

How did you get involved in the case?

Island Trees High School was filled with working class and middle class families. The community didn’t have a lot of money, and I remember people voted against the school budget several times. There was a fair share of prejudicial attitudes and views. I remember teachers being cautious about certain subjects discussed openly in the classroom.

I was at a school assembly in the auditorium one day. One of my favorite teachers, an English teacher, Mrs. Pepper, sat behind me and whispered in my ear that a number of books were taken out of the school’s library in the middle of the night. That’s the first time I learned of it. She took a chance to share this secret with me. She was a very good person besides being a teacher, and I’m sure she was morally outraged.

Did she get any credit for telling you?

I wonder if she ever got the full credit, because, to me, she was the person who started everything that was to happen. Great teachers inspire you in many ways. She did in English, and in her belief in me and my wife, Mary, as well. She wanted me to know because she believed I would do something about it. I was part of the school paper at the time and politically vocal in the school.

Why’d they pull the books?

The story I was told was that some members of our school board attended a John Birch Society meeting in upstate New York. There, they were informed of books in our school library that were offensive and had no place being available to high school students. They were given excerpts—only excerpts—that were said to be anti-American, anti-Christian, ant- Semitic (which I thought was funny since anti-Semitism already existed in the community), and vulgar. The board members returned and then proceeded to the school library in the dead of night, when everything was closed, and remove the list of books from the shelves. Nothing was said after the fact. It was done secretly. That is until Mrs. Pepper whispered into my ear sometime that week.

Then what happened?

Once we put the story into the [school] paper, the paper was banned. That escalated things. I remember going to the board meeting to protest the banning of the paper with friends, wearing a black armband. I was very excited. It was what I imagined the ‘60s to be and since I worshipped my sister, it also felt great to be active and a part of something bigger.

How’d the American Civil Liberties Union get involved?

I don’t remember how the ACLU was introduced to us, which parents they contacted, and how they found us. I also don’t know how many others they contacted. They did get involved relatively quickly.

It must’ve polarized the community.

My neighbor, who lived across the street and was a good friend of ours, was a member of the school board. It was awkward for the families, but I remember having no animosity toward him and separating my feelings towards him and the rest of the board we were fighting.

Looking back, I still believe they felt they were acting in the best interest for the students, but this is where the First Amendment is so important. They may have had the best of intentions, but it was their communal ignorance, not ever reading any of the books that they banned. That is why access to knowledge is so important.

Did you realize how important the Island Trees School District v. Pico case was at the time?

I think we thought it was very important for us to stand up to the board and not allow this to happen. I don’t remember if we ever put it in the context of having national implications. We graduated way before this went to the Supreme Court. It was the lower court that made the decision in our favor and forced the school to put the books back into the library. We celebrated that victory. It’s also important to remember that after the lower court’s decision, the community reelected the school board. The majority of the community was never on our side.

Was it a frightening experience?

I don’t remember ever being scared. We were different in our school to begin with, but I never felt like a complete outsider. I think having a girlfriend was a big part, also having an older brother and sister helped. Speaking strictly for myself, I loved it. My parents were very supportive and proud of what we were doing.

Why do you think people ban books?

I try not to vilify or judge people’s actions in that way. There are good intentions behind trying to keep kids safe and protected from what’s perceived as harmful influence and knowledge. But it’s knowledge and the visceral feeling in curiosity that makes us so special. Our advancement as a culture and society is based on it.

Are you surprised that books are still being banned more than 30 years after the case?

Maybe I’m more disappointed than surprised. The political and cultural positions throughout the country have hardened so much that I can understand why book-banning is still happening. It’s the same on the choice issue, the laws pertaining to voting, and the fight over what’s taught to our children. I know we’ve been through much worse times in our history, but being in this new technological age where there’s a full democratization of information, it’s just a shame that this continues to persist.

What was it like for you after the case was over?

The case took years, and we were all at separate colleges by then and living different lives. I found it satisfying, but at that age I was involved in other things so it wasn’t as significant as it might have been had I given it proper thought.

Do you ever think book banning is justified in a school or library?

No. I don’t.

Do your kids know that their dad helped make history?

That’s like asking if they think their parents are cool. I was privileged to be in the music business for over 25 years, and there’s nothing a parent can do be cool—or relevant—to their kids. We’ve spoken about it as one does about parents’ personal histories and journeys, but never in “historic” terms.

I spoke to the current librarian at Island Trees High School, and she says that the school tries to avoid controversy because of what happened.

I’m not surprised. Even though there was a victory from the Supreme Court, the culture that enables this belief is still vibrant in many areas. To just avoid the issue misses the point. It’s the ability to foster an atmosphere of respect for knowledge and the subsequent messy discourse that ensures growth and self-confidence.

Who is your favorite banned author and what’s your favorite banned book?

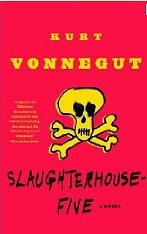

It has to be Kurt Vonnegut. I loved Slaughterhouse-Five. I then read all of his books. It was so great when they had a press conference that I was allowed to attend. There were cameras there, and we were sitting on a dais, but all I cared about was that I was sitting next to Kurt Vonnegut! He was chain smoking and incredibly nice to me.

Why is NCAC’s mission important to you?

I have a great deal of respect for what you and the NCAC do to stay proactive for this cause. There are few things more important than the desire to learn and the high value that needs to be placed on it. My father always taught me that history is a key factor in understanding our future, and if there’s anything troubling today it’s that there’s not enough quality information reaching everyone on our society. Besides poverty, ignorance is one of the most dangerous and insidious problems we face as a nation.

As Americans, we prize our freedoms and our rights, but we often forget that these come with responsibilities. One is to be an informed society. If we are ill informed and don’t ask the appropriate questions of our representatives and our community or do not act like citizenship is even a priority, we are setting a poor example for our children to follow, one that has dangerous consequences. This is a problem we face when schools are permitted to ban books.

By Debra Lau Whelan