See NCAC letter to Montrose High Principal here.

Student Cartoons Censored – A Creative Response to Censorship

For the past seven years, the art teacher at Montrose High in Montrose, Colorado has displayed the artwork of her students in the school hallways without complaint. However, in 2007, the school principal chose to remove three of the works, which she found “inappropriate.”

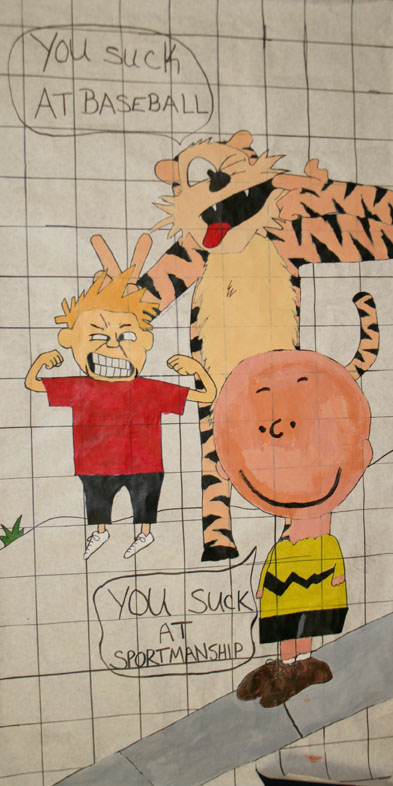

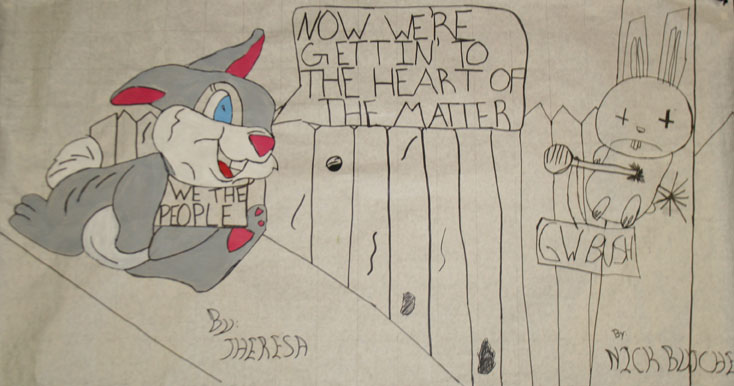

The works themselves are fairly innocuous (you can see them below). It is rather hard to imagine that a cartoon featuring a rabbit nailed to a wall and labeled as G.W. Bush with a dialog balloon reading “Now we’re getting to the heart of the matter” could be construed as promoting violence. No less arbitrary is the judgment that a cartoon referencing Martians, Earth holes and the womb is “indecent.” As to the use of the word expression “you suck at” in the third cartoon, this is, whether formal etiquette would allow it or not, a widely used expression today, especially in the schoolyard.

It is long established that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District, 393 U.S. 503, 506, (1969). While we recognize that school administrators have the authority to limit student expression when it could impede the educational process, it would be very difficult to prove that this artwork would have lead to any significant disruption. Moreover, the work does not violate any of the restrictive guidelines set by the school, including the ban on references to drugs, alcohol, or cigarettes. Some school administrators may have found the work personally distasteful, but that is not a legitimate reason for stifling student expression. Any attempt to “eliminate everything that is objectionable…will leave public schools in shreds.” McCollum v. Board of Educ., 333 U.S. 203, 235 (1948).

Furthermore, the decision to remove the students’ work without any advance discussion with the students themselves, while damaging it in the process, was educationally unsound and sends a noxious message to your students: if you disagree with something, just eliminate it, tear it down, silence it. This message completely contradicts the goal of an educational institution to foster informed citizens who value free speech, democratic dialog and cultural tolerance. Even worse, damaging the artwork promotes resentment on the part of the students and teachers who work so hard only to see the fruits of their effort trampled and disrespected.

We salute the work of the art teacher, Ann Marie Fleming, who turned this act of censorship into the perfect educational opportunity:

At first, Ms. Fleming, after a discussion with the students, took down the whole show in protest against the act of censorship. She told her students that she knew it was disappointing for them to be cheated out of showing their work, but that there is a certain amount of self-sacrifice involved in fighting for a cause.

The student newspaper covered the story. There were three stories and two letters to the editor. Early in the morning of the day the newspaper came out, the students hung an exhibit on censorship consisting of six posters, all of which were painted black. Written in white paint on each were the words: “This artwork was censored.” They then listed the artist, the title of the work, where and when it was censored. The six examples included the Nazis censoring 650 works from 1927-1937, an example of censorship from Cuba, the covering of Guernica by U.N. officials, the censoring of a manga book and of a video and the recent case at Montrose High, with the names of the six students and the date of 2007.

The principal requested that the display be taken down, but it did stay for long enough to make its point.

We salute the students at Montrose High for succeeding to channel their anger and frustration in a thoughtful exhibit, which expressed their feelings using peaceful civil disobedience and an educational approach.

We further congratulate their teacher, Ann Marie Fleming for resisting the efforts the administrators made to intimidate her by asking her bring to the meeting a copy of her lesson plan and all the reference material she used during the course of the project. (For the past 7 years she had taught the class, the principal had never before asked for a lesson plan.)

Thinking creatively and turning a censorship incident into an opportunity to support free speech is our best weapon against the censors!

|

by Jordan DeJulio and Georgiana Hinkson |

|

by Aaron Padini and Henry Arnold |

|

by Nick Butcher and Theresa Armstrong |