Censored Artists and Their Stories

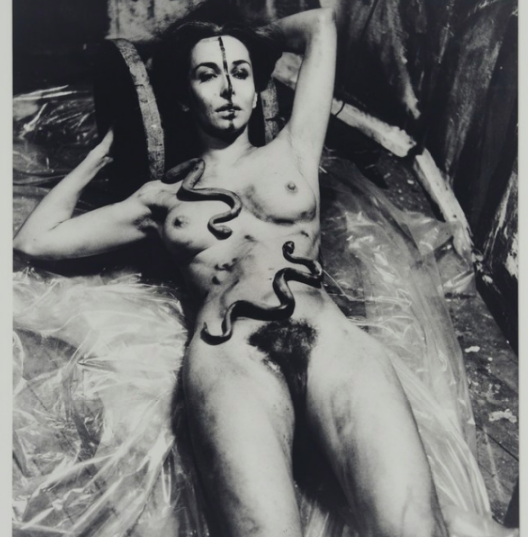

Images of Carolee Schneemann’s performances, which so many people posted during the week after she died, were taken down repeatedly and en masse because of her nudity.

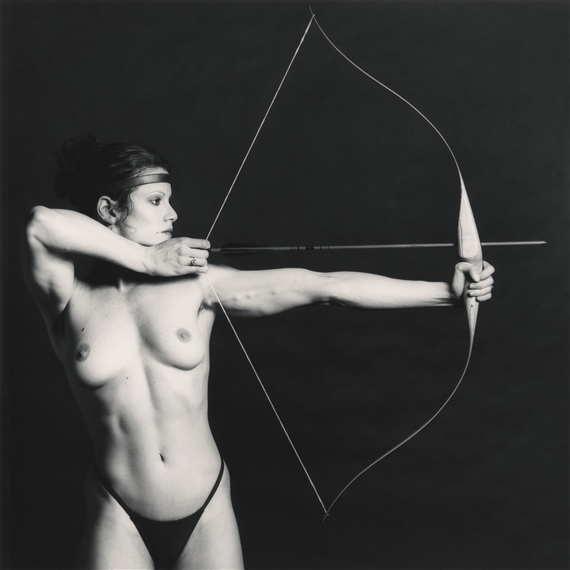

Fotografiska, a contemporary photography museum in Stockholm, censored promotional material for its upcoming Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition to draw attention to Facebook’s strict nudity ban. The photographs were covered with a large blue rectangle with the text “facebook-friendly square”. The museum’s purpose was to bring attention to the issue and stimulate discussion. “We censored the photographs because Facebook removed our pictures,” said a Fotografiska spokesperson. “Facebook thinks that naked bodies cause offence. They remove our photos. For them, it does not matter if it is art or not. If you would like to see the photos in their full glory, we invite you to visit us.” The museum affirms that Facebook is an important channel for the museum to market its exhibitions and to conduct a dialogue with its fans. Its decision to “censor” the Mapplethorpe nudes was taken with this in mind. “It is a company which is all over the world; values differ and do not always meet with our Swedish values. We understand their position, but at the same time we don’t think that it is right.”

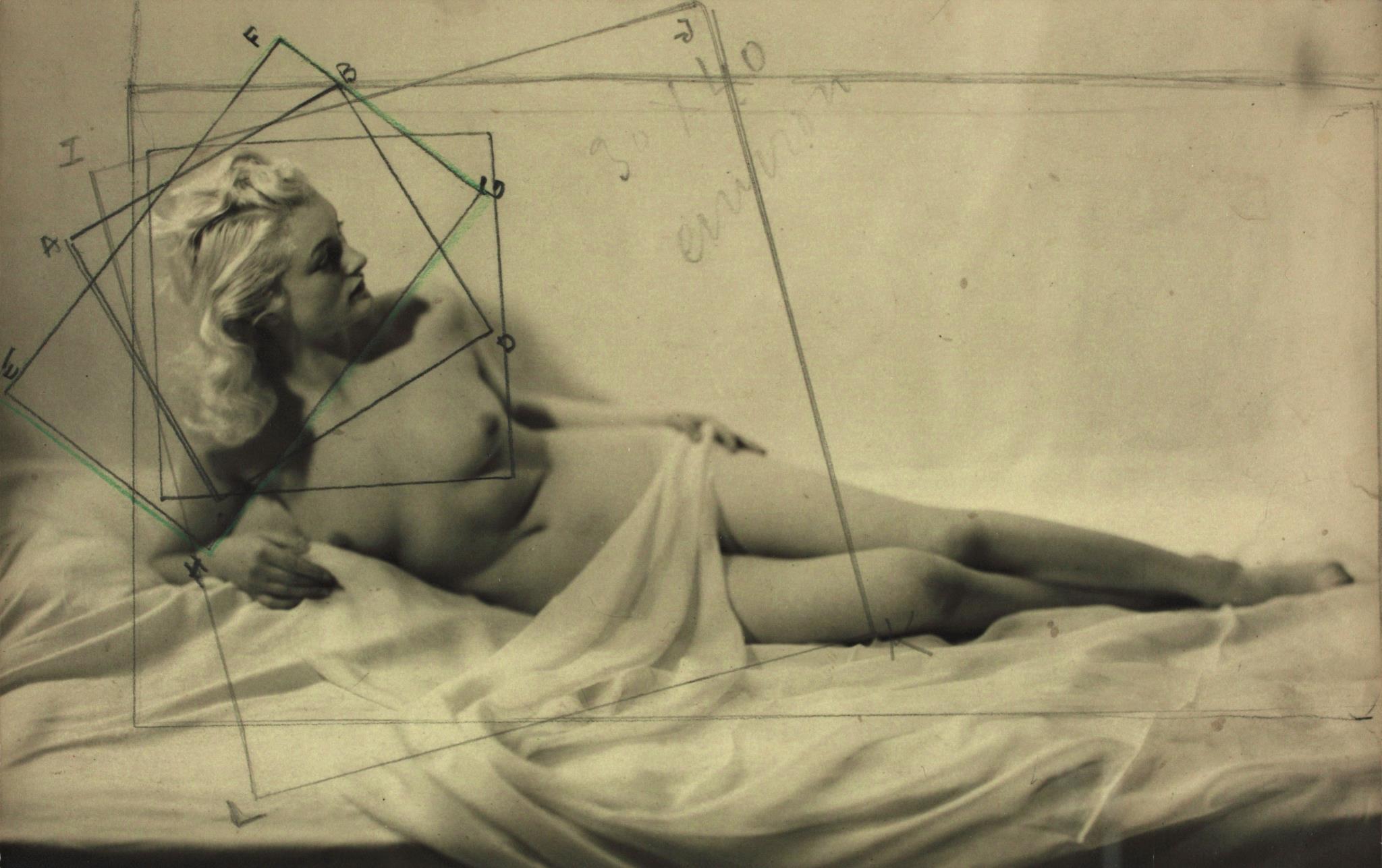

A 1940 nude study by photographer Laure Albin Guillot on view at the Jeu de Paume in Paris was removed from the museum’s Facebook page because it violated “community standards.” The page itself was shut down for 24 hours. The museum reposted the photo with a censor bar over the bare breasts and said it would no longer be able to post nude photographs of artistic value, adding: “This discussion ought to provoke Facebook’s administrators to reconsider their position. To not be able to differentiate between an artistic image and a pornographic one is a dubious fudging and, most of all, a dangerous one.” A Facebook spokesman responded: “With reviewers all over the world dealing with millions of reports a month, it’s difficult to distinguish between art and pornography from either a policy or practical level.” It seems a bit of a stretch to suggest that a world-famous museum would make a habit of posting porn.

Instagram took down Dublin-based photographer and artist-in-residence at the Irish Museum of Art Dragana Jurisic’s account for an image she posted – a nude photograph of the artist Caoimhe Lavelle (part of Jurisic’s ‘100 Muses’ series), but with the parts Instagram bans (female nipples and genitals) fully covered. The image was made precisely so as to conform to Instagram’s TOS, yet it was taken down together with thousands of other posts that constitute Dragana’s visual diary.

“It would be tough for me as an artist to be cut off from this method for sharing my work. Social media, crowdfunding projects and the whole DIY mentality has been an invaluable resource for most people, especially artists, freelancers, musicians and anyone with little money who needs to spread the word about their work.”

“I posted 3 installation images from the exhibition IN THE CUT at Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken in Germany. They are all images from [my series] “love in the ruins; sex over 50”, and in fact, the two that remain posted are more explicitly depicting intercourse. I was told there is an algorithm that searches for nipples (no idea whether this is true) but this image has them. It was taken down within less than an hour, with a message that I offended “community standards”.

“Hey IG There’s no nudity here! This photo of my new act about body love was just removed from both my FB profile and fan page, as well as my IG! In my act I wipe the word NO off of my body and write YES, and invite others to write on my skin. Removing this photo that contains no nudity is saying my body is unacceptable. My body is beautiful. Get it together.”

“The Burlesque community still heavily relies on FB and IG both to stay in touch as well as spread the word about our shows and workshops. Lots of casting happens on these platforms, and many of us get gigs from producers who happen upon our work. Visual representation is key for what we do.”

Click here to learn more about Lillian.

“I am a fine art photographer whose work explores femininity, loneliness and individuality. I use Instagram to show my work, build an audience and discover other artists. The worst and most baffling instance of a post being removed for “violation of terms” was a picture of my 8 year old daughter. People have told me there’s a “nudity algorithm” that automatically detects too much body showing but I’ve had posts up for hours before they get removed and I can’t help but feel they are being reported by someone who just doesn’t like me and/or my work. Plus I’ve noticed as I’ve gained more followers over the past year I get posts removed more often.”

“I heavily rely on both Facebook and Instagram, both to increase my exposure and to, mostly, network, communicate and keep an eye on what goes on in the photography world, what other artists and curators are up to, discover open calls, etc. Instagram removes individual posts (or stories) any time I post uncensored photographs of female breasts. They’ve been removed because it “breached the community guidelines” and to respect “different sensitivities” of audiences around the world. Another memorable time was when IG removed Sally Mann’s “Three Graces” (three women on a top hill, peeing standing holding each others hands) – I tried to upload it so many times and it was deleted over and over again.”

"I truly believe censorship of the arts is dangerous for societies around the world. Facebook is essentially curating the world we live in to a point that we are regressing in so many areas and the majority of people I feel are blind to this. I have been deleted and reinstated 9 times on Instagram, completely removed from Facebook and had my Tumblr account reduced to a saintly level of images. I'm exhausted from battling censorship, I'm sad I have to play their game to stay in the game and I'm exhausted from social media as a whole! In the past few years I have seen other petitions, movements and campaign's try to go up against Facebook and its abhorrent regulations but they stand behind a wall more real and 10 times thicker than Trump's would ever be. At present I feel I have a defeatist attitude to your campaign but wish I had the energy and drive to stand up and fight as I did in previous years. Social media is built on an unbalanced and unfair model, and what we really need is entirely new platforms to move forwards. People like Jaron Lanier have some great ideas of how this could work and if you are unfamiliar with his ideas please go and check out his Ted talks or books."

"The first time I remember censorship coming out of the blue on social media in a way that felt just really wrong was in 2016, when a friend posted a great photo of her visit to the National Portrait Gallery to see my work on display there. It was a cool shot of three people in silhouette sitting in front of my large painting. It was hanging in the Smithsonian — a huge honor for me. And then her photo was deleted from Instagram, for "not following community guidelines". It's a painting of a torso, mind you. Just a torso. That happens to be female-presenting. That happens to be fat. It began happening with greater frequency over the next few years. I have been repeatedly kicked off of Facebook for periods of time ranging from three days to a week, which, when the reason was a review of a solo show, felt both like very bad timing and a professional interruption. That review of my solo show, which was published on Hyperallergic, was banned from Facebook. No one could post it. I've since left Facebook, but I use Instagram regularly. Instagram is an important platform for not just artists, but art institutions such as galleries and museums. Despite the fact that the guidelines say that paintings and drawings of nudes are allowed, my paintings of torsos get censored there with regularity — I'd say several times a month. And every time it happens, it is followed up with several weeks of "shadowbanning." A shadowban isn't announced, but it's unmistakable, chiefly by the fact that your hashtags do not work. Your posts under any given hashtag just don't show up in the hashtag feed. The fact that this happens with such regularity means that I can almost never use hashtags effectively on Instagram, because I'm pretty much always being shadowbanned. It's a way of curbing your voice. Recently when I was censored I asked my followers to "report a problem" — complain — to Instagram on my behalf. This was a few weeks ago, and I haven't been censored since. I wonder if the complaints had an effect, but I would be shocked if the censorship were to stop. Stay tuned!"

"My IG account was suspended in April. I had more than 100,000 followers. I have appealed to IG many times, but I receive no reply. I immediately created another account. That account was suspended within a week. The account I created next was suspended without warning. Most of my images are female portraits and there are figures wearing underwear, but none of them are naked at all."

"I had recently graduated with a BFA in fashion and textiles and posted a photo upon the completion of my thesis collection. The collection was focused on finding the balance between protection and vulnerability, as well as celebrating the strength that exists in being soft. The garments ranged from covering the body (protecting it), to exposing it (making it vulnerable). The emphasis of the collection was placed on the dress that represented being fully vulnerable; a sheer dress made from tea-dyed, ethically sourced silk organza and silk habotai. Within 24 hours the post had been removed and I was unable to make any sort of contact with Instagram about having it re-instated. I would like to say that I struggled with their review process, but I wasn't even able to get access to it. It felt like running into a brick wall. A message just popped up saying my image did not meet the community guidelines, which are intended to 'keep the community safe'. Having felt that my image in no way made Instagram an unsafe online environment, especially considering the intention behind the work which is one of empowerment, I tried multiple times to contact them to no avail."

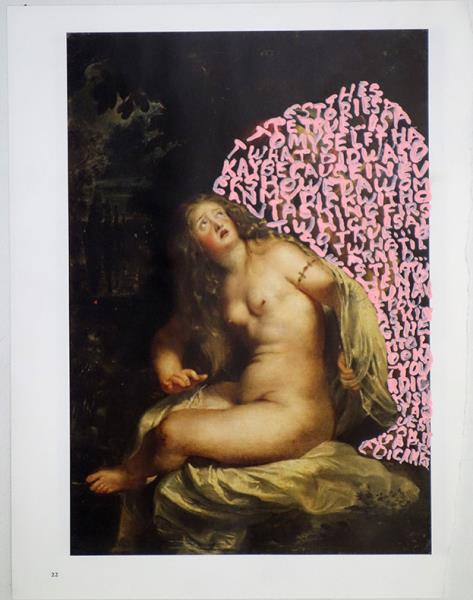

Betty Tompkins is an American painter whose works revolve, almost exclusively, around photorealistic, close-up imagery of both heterosexual and homosexual intimate acts. She creates large-scale, monochromatic canvases and works on paper of singular or multiple figures engaged in sexual acts, executed with successive layers of spray painting over pre-drawings formed by text. The weekend of April 27-28, Instagram de-activated her account.

Alongside artists such as Carolee Schneemann, Yoko Ono, Valie Export, Joan Semmel, Lynda Benglis and Judy Chicago, Tompkins has been re-assessed as a pioneer of Feminist art. Tompkins is listed in The Brooklyn Museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art's Feminist Art Base. Her first painting, completed in 1969, is held in the permanent collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, France.

"Instagram and Facebook have constantly removed my photographs, as well as news articles I've posted about my artwork and exhibitions. When Huffington Post ran a review of my photographs, many of them of nude queer women, Facebook kept deleting the article from my timeline and from the timelines of others who shared it. IG has also flagged and removed my photographs for violating 'community standards' many times.

Social media platforms are now a major force in the art world, and artists rely on them to publicize their work and create communities. Social media guidelines that censor feminist and queer artwork limit what kinds of bodies can be visible in our world. They also block opportunities for artists who work with bodies that don't fit ideals of how bodies are 'supposed' to look, further erasing our lives and identities, as well as our ability to shape our own representation."

"Grab Them By The Ballot is empowering women and stripping away the layers of shame around our bodies and sexuality. We reveal the political and societal measures taken to control our bodies and encourage female voter turnout in 2020. We promote artist intervention for women’s rights. We educate the public on intersectionality, legislation measures to control our bodies, sexual and bodily empowerment and healing the collective sexual trauma through photos and shared stories of healing.

Alaitz Gómez is a painter and photographer from Donostia, Spain who explores the nude female body as subject.

Gómez writes that Instagram has been an invaluable resource for her. It has been a way for her to increase her exposure and create a like-minded creative community. Unfortunately, Facebook and Instagram’s nudity ban limits what artwork she can share and her ability to network with other artists. To be cut off from two of the world’s largest social media networks is devastating for emerging artists like Gómez who trying to change the conversation surrounding the female body.

"Out of fear of destroying my photography business/income (I know many artists who have had their accounts forcibly deleted), I have diligently digitally removed female nipples for years to comply with Instagram and Facebook's misogynistic censorship policies, but have still had many photos removed on Instagram with threats of account deletion and have had my Facebook profile temporarily locked. I originally posted this photo on Instagram with a detailed description of how I blurred the nipples in Photoshop to comply with IG censorship without disfiguring the female form; after the THIRD time Instagram deleted this censored photo of a nude woman merely sitting in sadness and threatened to delete my account over it (even though I altered the nipples more each time), I finally snapped and began working on my womxn empowerment series to fight misogynistic censorship and the culture it perpetuates. These archaic censorship policies not only negatively impact artists' abilities to earn a living, but they also negatively impact every womxn who needs to interact with men who have been conditioned to believe that the female form is an objectively sexual entity that needs to be hidden from the male gaze, used for male pleasure, or hyper sexualized to sell products. It's 2019; there is absolutely no acceptable justification for forcing womxn and their bodies into submission ever again, and I am glad to be fighting for what's right with many talented and caring fellow artists."