In the late 18th century, novels took Europe by storm. Due to an overall rise in literacy, an expanding marketplace and stronger printing capabilities, this form of immersive content exploded in popularity. Women, whose roles in society were predominantly limited to wife, widow or spinster, became the most avid readers. Romantic novels, being relatable yet fantastical, were particularly popular. They offered a healthy escape from the monotony of daily life. Many, however, were less than enthusiastic about this new trend. Self-identified moralists in particular were horrified by this sudden uproar of female readers. Take this passage from journal Sylph no. 5, October 6, 1796: 36-37

Women, of every age, of every condition, contract and retain a taste for novels […T]he depravity is universal. My sight is every-where offended by these foolish, yet dangerous, books. I find them on the toilette of fashion, and in the work-bag of the sempstress; in the hands of the lady, who lounges on the sofa, and of the lady, who sits at the counter. From the mistresses of nobles they descend to the mistresses of snuff-shops – from the belles who read them in town, to the chits who spell them in the country. I have actually seen mothers, in miserable garrets, crying for the imaginary distress of an heroine, while their children were crying for bread

Moralists feared that these literature-obsessed ladies would be unable to distinguish fact from fiction. Surely, they believed, young ladies who cried “for the imaginary distress of a heroine” would eventually lose their grip on reality.

Today, we all know how right those moralists were; the streets of 18th century Europe ran red with blood spilled by ladies who mistook themselves for Bertha Mason, and that’s why no one reads anymore.

Well… actually that’s not exactly what happened.

Women kept reading and the world kept spinning and so, eventually, this great moral panic subsided. Sexism is a simple answer as to why people bought into this line of reasoning, and certainly, there are sexist components to the 18th century moralists’ viewpoint. However, this answer is not all-encompassing. Romantic fictional content was certainly not new to 18th century audiences. After all, each production of Romeo and Juliet had not been accompanied by a rise in female suicide.

So why then, did 18th century moralists think novels were so different, so dangerous?

In a single word: Immersion.

Fear of Immersion

As the moralists saw it, the fundamental difference between a romantic play and a romantic novel was that novels were far more immersive than anything that had come before. Novels were always accessible due to their portability and far more relatable because they were tailored for a particular audience. The idea that people could ever confuse the written word with reality may sound crazy to our modern sensibilities, but actually, the underlying belief has been retained in our worldview.

As the moralists saw it, the fundamental difference between a romantic play and a romantic novel was that novels were far more immersive than anything that had come before. Novels were always accessible due to their portability and far more relatable because they were tailored for a particular audience. The idea that people could ever confuse the written word with reality may sound crazy to our modern sensibilities, but actually, the underlying belief has been retained in our worldview.

Within our culture, there seems to exist a belief that fiction, when presented in the right way, can consume us. We fear that the “I” in a narrative can somehow be confused with ourselves.

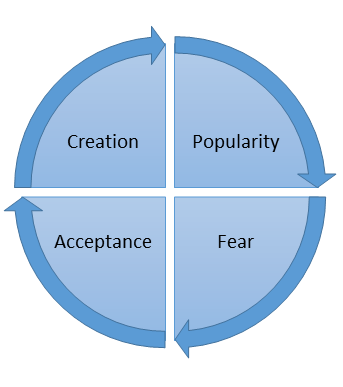

Time and again, it has proven to be unfounded, yet this fear—that fiction can somehow render us incapable of separating real from imaginary—is constantly reoccuring. First, a new type of fictional content will rise in popularity. Following its popularity, it will criticized for being too dangerously immersive. Finally, these accusations are ultimately proven false. The cycle then repeats itself once a more immersive form of storytelling is created.

We need only to flash forward to the 20th century for an example of this same cycle of events.

The D&D Panic of the 1980s

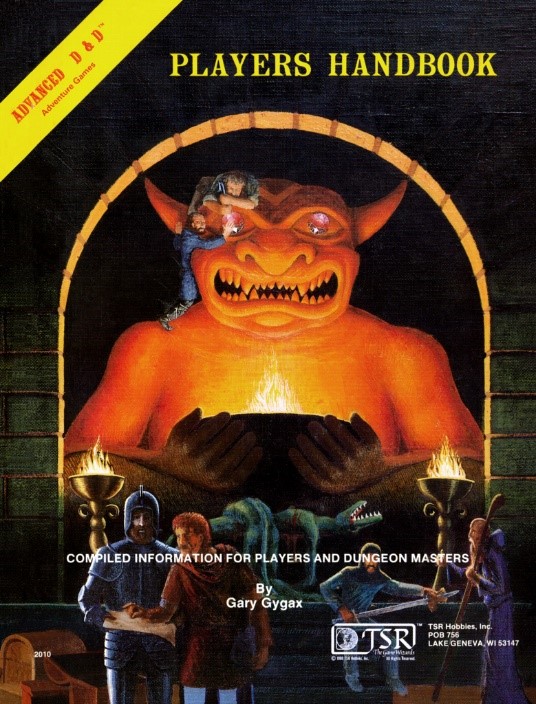

It was 1979. Billy Idol was just about to start dancing with himself, the Empire was poised to Strike Back and Gary Gygax finally finished adjusting and reorganizing the rules to what eventually became the 1st Edition of Dungeons and Dragons.

Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, as it was then named, was a fine-tuned version of the game he and Dave Arneson had published four years prior. The core concept of D&D wasn’t much more than a number crunchy Choose Your Own Adventure novel with a randomized (dice rolling) component. There were, however, two key differences that would propel this game to both popularity and heavy scrutiny.

First, the game was not a solitary pastime, it was designed to be played as a group activity. Second, instead of being given a set of choices or adventure paths, one person, the Dungeon Master or DM, would be responsible for creating the fictional adventure. For example, if I tell the DM that my character walks into a bar, the DM tells me what’s inside. Then, if I ask the barkeep a question, the DM, temporarily playing the role of the barkeep, will answer.

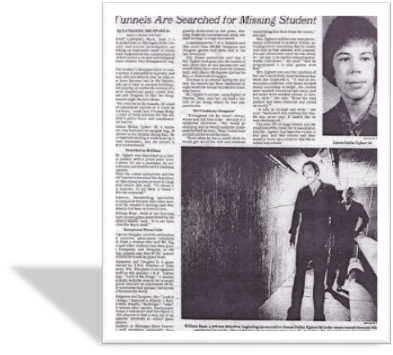

The ability to create a limitlessly immersive narrative quickly met harsh negative press and fear mongering. Making matters worse, just months after Gary Gygax released AD&D, a child prodigy and frequent D&D player James Dallas Egbert III tragically dissappeared, forcing the game into a media hailstorm of misunderstanding and fear.

Egbert, often the DM of his playgroup, mysteriously disappeared during his time at Michigan State University. The family hired William Dear, a private investigator, who, after hearing about D&D in abstract, theorized that during a D&D session, another student had confused reality with fiction and accidentally killed Egbert. This theory was ultimately proven false.

Dear later wrote a book apologizing for his mistake. The damage, however, was already done. Once the media caught wind of Dear’s incorrect theory, D&D’s ability to tell unique, immersive stories switched from a selling point to a potential danger. People came to believe that this story-based game had the power to trick teens and young adults into killing themselves and each other.

Writer Rona Jaffe capitalized on this fear by fictionalizing the untrue events in a novel titled Mazes and Monsters. The novel was quickly adapted into a made-for-TV film that further distorted the reality of the situation. The takeaway of the film is clearly demonstrated in the clip below.

.

By the time the Breakfast Club was in session, the reputation of D&D and other such games had taken such a blow they are arguably still recovering from it.

The level to which this paranoia parallels the moral panic over women and romantic novels in the 18 and 19th centuries is startling.

To solidify this point, we can observe another more recent media controversy.

Video Game Panic of the 1990s

Most of these events are still within recent memory and NCAC has already written about this topic at length: you can check out NCAC’s detailed timeline of video game controversies for more detailed information. In brief, after several violent incidents involving teens who played video games– the most famous being the Columbine Massacre– people were led to believe that video games were responsible for provoking these tragedies.

Most of these events are still within recent memory and NCAC has already written about this topic at length: you can check out NCAC’s detailed timeline of video game controversies for more detailed information. In brief, after several violent incidents involving teens who played video games– the most famous being the Columbine Massacre– people were led to believe that video games were responsible for provoking these tragedies.

The media and public outcry became so strong that research began in order to uncover possible links between violence and video games. Days before a particular study conducted by the Surgeon General was published, many media outlets felt so sure of its results they reported the study would conclusively prove a link to violent behavior and video games. After all, they thought, nothing in history had been quite as immersive as video game.

However the study, shockingly, came out against a causal link between violent behavior and video games. As more and more research came out regarding the topic– almost all saying the same thing– the narrative became less and less popular. As PhD Lawrence Kutner later wrote:

It’s clear that the ‘big fears’ bandied about in the press – that violent video games make children significantly more violent in the real world; that children engage in the illegal, immoral, sexist and violent acts they see in some of these games – are not supported by the current research, at least in such a simplistic form. That should make sense to anyone who thinks about it. After all, millions of children and adults play these games, yet the world has not been reduced to chaos and anarchy.

Looking Forward

We’ve seen the cycles of creation, popularity, fear and acceptance play out three times now. It all seems so predictable, so why not predict what we’ll be up in arms about next? At this year’s E3, a wide range of virtual reality titles were revealed and, assuming some of these titles are popular, the gaming marketplace is soon to be flooded with them. Dissenters will, no doubt, rail against this new form of immersion and look to censor this new technology.

Maybe, however, it’s time to change our perspective, based on the centuries of experience, about fiction’s power over us.