Last week, after a six month long process, a U.S Court of appeals ruled in favor of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in their upholding of the principle of "net neurality," which had been challenged by a number of Internet Service Providers (ISPs).

Last week, after a six month long process, a U.S Court of appeals ruled in favor of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in their upholding of the principle of "net neurality," which had been challenged by a number of Internet Service Providers (ISPs).

As the National Consitution Center's blog puts it, net neutrality is the principal that "all internet traffic is created equal." Essentially, this means that an ISP should be prevented from charging companies or organizations with powerful domain names for faster connection speeds. On June 14th, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit deemed– in accordance with the FCC– that an ISP's product, broadband internet, is an essential ultility and must be regulated as such. In legal terms, it must be regulated strictly as a "telecommunications service," not more loosely as an "information service." According to the Washington Post, like telephone network providers, ISPs "can't use their position in the marketplace to unfairly benefit themselves and shut down competition."

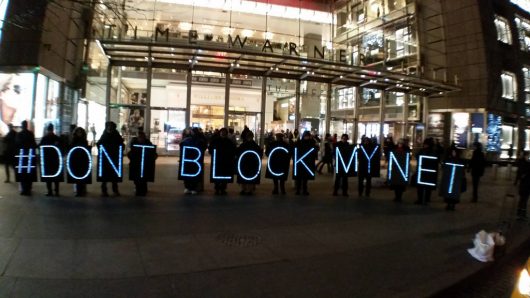

For the NCAC, this is an important victory. In 2009, the FCC first announced its support for the principle of net neutrality, coined originally in 2003, describing its function in the protection of an open internet. Three years prior, NCAC produced a resource that explored the importance of net neutrality in protecting the internet from censorship. The resource highlighted that without neutrality, an ISP like Comcast would be able to make other "companies' services inconvenient or altogether impossible, all in order to promote their own products and agendas." In a worst case scenario, NCAC hypothesized this could amount to a shutting down of free speech on the web.

The telecom companies who opposed, and lost, to the FCC in court argued that the ultility classification constituted an unjust level of government regulation in their business providings. For one, they argued, a product like email is more accurately described as an "information service" not a "telecommunication service." The telecom companies also reupped a complaint the NCAC highlighted in 2006, the "bogus" argument that this sort of government interference amounted to an infringement of these companies' First Amendment rights. As the Washington Post reported:

In carrying speech-like content over their networks such as videos or blog posts, ISPs can be said to be "speaking" when they agree to transmit that content. Any rules that infringe on their ability to do that amounts to an attack on free speech.

The NCAC's rebuttal went as follows:

NCAC would not typically support a measure to "regulate" the transmission of information in any way. But in this case, some government intervention is necessary to protect free expression and access to information from interference – not from the government, but from powerful interests whose only priority is profit.

The court, however, rejected the ISP's consitutional argument on the basis that although "telephone networks carry other people's speech," this does not make the companies themselves speakers protected by the First Amendment.

Interestingly, one of the key supporters of net neutrality was the late conservative Supreme Court Justice, Anthony Scalia. In 2006, Scalia argued internet providers were like pizzerias. ISPs argue that they do more than provide the utility that is the internet. They also offer, for example, email accounts and high speed connections. But Scalia argued that a pizzeria does more than make pizza, it also delivers it. However, a pizzeria does not usually advertise as a delivery service. Essentially, like purchasing a pizza that comes with delivery, when consumers make use of an ISP, they buy a telecommunications service that also comes with information services.

Although this is not the end of the battle for net neutrality– a number of the ISPs are planning on appealing the court ruling claiming it hurts their competitiveness and hinders innovation in the industry– from the NCAC's perspective, the court's decision marks a positive step in the upholding of a free and open internet.