A new survey shows that while Americans might have trouble explaining which rights are enshrined in the First Amendment, they mostly support free speech in practice.

One of the most interesting lines of discussion the Institute raised concerns student speech. For the last several years, a prominent controversy surrounding the First Amendment has been clarifying the rights of students to post content online without repercussions from their school. Some confusion on the part of officials is to be expected; protests or frustrated tirades have been emblematic of adolescence for generations, but never before have young people been able to speak out with such speed and scope. Yet although the Supreme Court has held since 1969 that student speech can only be restricted if it "materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder" (Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District), the Justices have been tight-lipped as to how this standard applies in the 21st century.

In that gap, school districts across the country continue to enact (or threaten) punishment for students making relatively harmless tweets or status updates off-campus. For example, in 2012, a 13-year-old Minnesota girl was suspended after she badmouthed a hall monitor on Facebook after classes. Her lawsuit alongside the ACLU emerged victorious in 2014, but the stress and embarrassment of the proceedings could not be remedied. And in April 2015 (as previously noted), police officers informed students of Pennsylvania's Plum Borough School District that they could be arrested for talking on social media about a sex scandal involving two teachers.

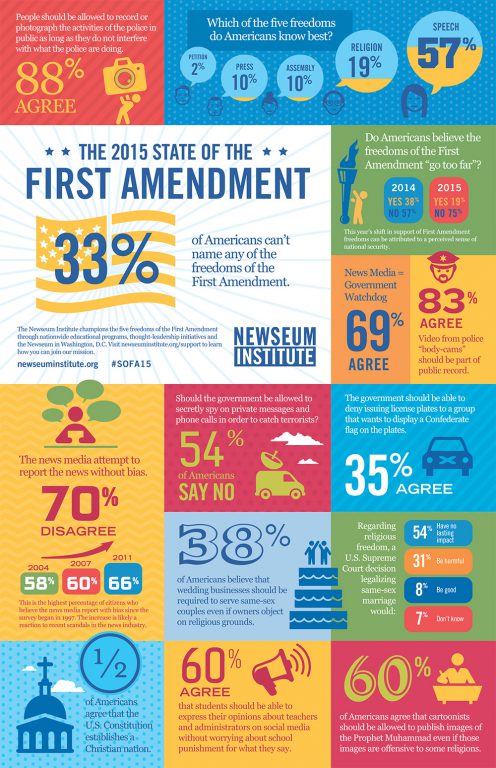

The Newseum survey revealed this state of First Amendment consensus: Almost 60% of adults agreed "[s]tudents should be allowed to express their opinions about school administration without threat of being punished." Perhaps unsurprisingly, those in favor of broader student speech were overwhelmingly young: 84% of respondents between 18 and 29 years of age agreed with the statement, compared to 60% of those over 30.

To the young or old, though, school officials' overreactions might be understandable; online harassment can be a crime. However, cyberbullying laws should be drafted and interpreted narrowly. To put student gripes, grievances, or raunchy jokes on par with true threats of violence does damage to the First Amendment and developing children's psyches alike.