*UPDATE: Good news! Just a week after NCAC’s letter, a review committee voted to keep Palomar on the school library’s bookshelves.

A mother in Rio Rancho, New Mexico has called Gilbert Hernandez’s acclaimed Palomar: The Heartbreak Soup Stories a collection of “child pornography pictures and child abuse pictures.” After her son brought the book home from Rio Rancho High School library, the parent flagged some 30 “inappropriate” pages and brought them to the attention of school officials. Local news channel KOAT reported that the unnamed officials agree the book is “clearly inappropriate,” and are now caught in the throes of investigating how it became a part of the library’s collection in the first place.

In response to this challenge, NCAC has sent a letter to Rio Rancho Superintendent V. Sue Cleveland, urging for the book to be kept on shelves in accordance with basic constitutional and educational principles.

According to the school district’s policies, library materials under reconsideration should be “treated objectively, unemotionally, and as a routine matter.” Reviews of challenged materials require a written formal complaint, followed by an evaluation of the material in question by an appointed review committee. Given the moral panic evident in the local news broadcast, it is unclear whether those policies were followed adequately.

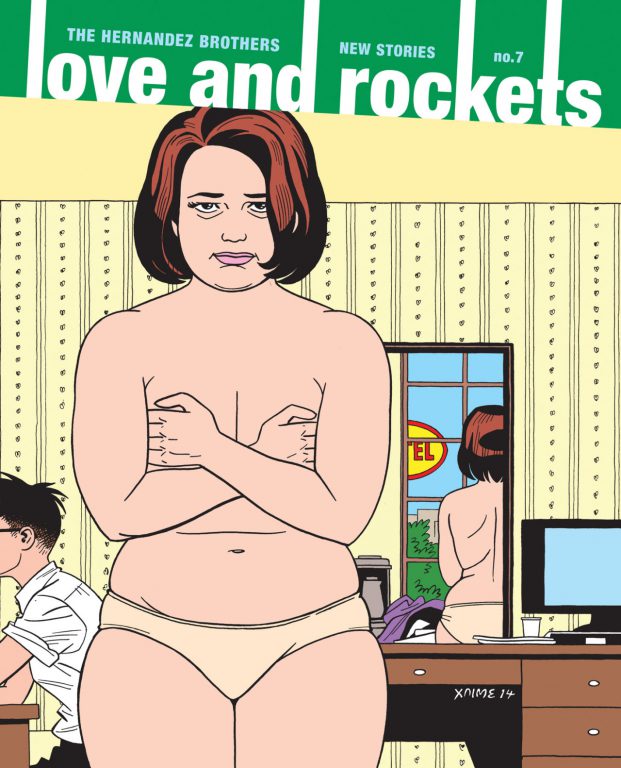

As NCAC’s letter states, the allegations of child pornography hurled at Hernandez’s work are entirely baseless. The Supreme Court has historically defined child pornography as including images of actual children, not drawings or other artwork. The images in Palomar are not meant to be salacious, and deserve to be seen within the context of his entire work. Palomar is part of the Love and Rockets series, created by brothers Jaime, Gilbert, and Mario Hernandez, about a generational family drama in a fictional Central American town. One of Time Magazine’s Best Comics of 2003, Palomar has attracted critical acclaim for its unflinching, lyrical exploration of culture, sexuality, and memory. Indeed, the Times of London called the book “the graphic equivalent to the fabulism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the Nobel laureate,” while Publishers Weekly referred to it as “a superb introduction to the work of an extraordinary, eccentric and very literary cartoonist.”

“The task of selecting school library materials properly belongs to professional librarians and educators,” the letter states. Indeed, Palomar has gone unchallenged since it entered the school library’s circulation system in 2006, when “it was presumably chosen by a librarian who possesses the adequate knowledge, training, and expertise to make decisions about what books belong on shelves.”

Removing the graphic novel not only ignores the merits of the book as a whole, but also fails to uphold the library’s duty to serve all readers regardless of individual tastes and sensibilities. No one parent should have the right to suppress access to content for all of the district’s children, since there are undoubtedly some parents — and, more importantly, students — who would appreciate Palomar.