On August 1, 1989, the FBI's Milt Ahlerich sent a letter to Priority Records — which distributed N.W.A's debut album Straight Outta Compton — to register his feelings about the song "Fuck tha Police," which he said "encourages violence" against law enforcement officials. And he made clear that these were not merely his personal views:

I wanted you to be aware of the FBI's position relative to this song and its message. I believe my views reflect the opinion of the entire law enforcement community.

The letter drew sharp criticism. As the LA Times reported at the time, Danny Goldberg of the ACLU of Southern California said it was "completely inappropriate for any government agency to try to influence what artists do." And the ACLU's Barry Lynn commented, "It would not violate the First Amendment for an individual working for the FBI to personally write such a letter. But it's incredible for the FBI to send this kind of official letter to any person in the creative community.

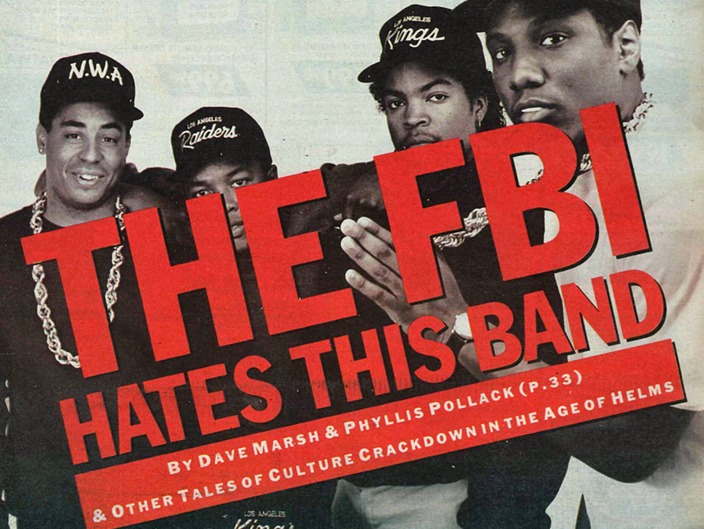

The letter was the subject of a recent lengthy piece in the Village Voice by anti-censorship activists Dave Marsh and Phyllis Pollack. Ahlerich insisted that he did not mean for it to be intimidating, but the Voice investigation noted that it fit into a pattern:

An informal police network faxes messages to police stations nationwide, urging cops to help cancel concerts by N.W.A., a group based in Compton, California. Since late spring, their shows have been jeopardized or aborted in Detroit (where the group was briefly detained by the cops), Washington, D.C., Chattanooga, Milwaukee, and Tyler, Texas. N.W.A. played Cincinnati only after Bengal linebacker and City Councilman Reggie Williams and several of his teammates spoke up for them.

And as the Daily Beast reported, there were other government officials happy to step into the mix: "The Minnesota attorney general wanted to prosecute record stores that sold Straight Outta Compton (the album that includes “Fuck tha Police”) to minors. Politicians, both conservative and liberal, rushed to the nearest mic to denounce the song and the Compton hip-hop group."

More than anything, the Voice report serves as a reminder of the pitched battles over rock music's supposed to threat to young people:

Police pressure forced the cancellation of a June 17, 1987 Run-D.M.C./Beastie Boys show at the Seattle Center Coliseum, beginning a new cycle of such abuses that trace back to the heyday of Alan Freed. Last May, Ouachita County, Arkansas, sheriff Jack Dews seized rap and heavy metal tapes from a Wal-Mart from the Heart of the Blues record store in Camden, claiming the music was obscene under state law and couldn't legally be sold to anyone under 17. In August, the 203,000-member Fraternal Order of Police declared a boycott of any musical group that advocates assaults on police officers, a significant stand since off-duty cops staff most concert security teams.

Billboard's September 9 front page detailed nationwide efforts to repress acts "that swear, engage in erotic posturing, and sing lyrics touting violence." It reported curtailment or cancellation of shows by Skid Row, Too Short, GWAR, and N.W.A., as well as the arrests of Bobby Brown in Columbus, Georgia, and Skid Row's Sebastian Bach, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Among the other towns where local officials censor rock are Cincinnati and Toledo, Ohio; Erie, Pennsylvania; and the Poughkeepsie and Syracuse, New York.

Before one gets too comfortable with the idea that the bad old days of the Parents Music Resource Center are all in the past, consider the fact that just weeks ago a show by rapper Chief Keef was shut down by authorities in one city in northwest Indiana — after city hall officials in Chicago allegedly pressured a venue to cancel the show there. As Marsh wrote recently: "Early censorship attacks are always greeted as no big deal, and they are always harbingers of worse to come."