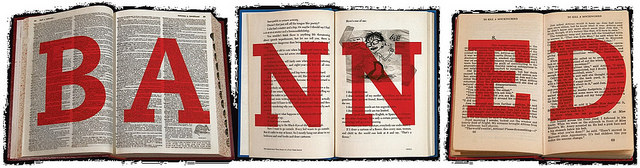

Is America embracing book banning?

That’s the main question that emerged from a recent Harris Poll. The headlines generated by last month’s survey came from a simple question: “Do you think there are any books which should be banned completely?” A total of 28 percent of respondents said yes. This is a jump from the last time Harris asked the question four years ago, when 18% answered affirmatively.

But before you despair over Americans’ embrace of book banning, consider the question they were asked: Should any book be banned. While a free speech absolutist would have one answer — the same one, incidentally, as the majority of respondents did: No — it is worth wondering what the ‘yes’ responses had in mind. A how to guide for would-be terrorist bomb makers? Mein Kampf? A collection of child porn?

In other words, answering yes to that question might not reveal an emerging appetite for censorship. The caveats and what-ifs are endless. As a matter of fact, back in 2011 when Harris did a very similar poll, they included about a question about the debate over substituting the word “slave” for the word “nigger” in Huck Finn. The vast majority of respondents opposed it — a pretty strong indicator that when faced with a specific instance of censorship, Americans are more protective of free speech than a knee-jerk response to a general question might suggest.

There are other problems with how to interpret the poll’s findings. Harris asked a series of questions about whether children should be permitted to get books with sex or violence from a school library. But is the ‘child’ in question in elementary school — or in middle school or high school, where students do read such books — and where the First Amendment prevents schools from blocking access to such work just because some people don’t think they’re appropriate.

So does a poll like this tell us anything? Maybe. If you care about the relationship between political affiliation and attitudes, the Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell noted that the poll shows that Republicans have more enthusiasm for book banning. And that sentiment carried over to media too: “Republicans were also more likely to say that some video games, movies and television programs should be banned.” But that’s not the whole story; as she pointed out, “Liberals and conservatives… seem pretty keen on trampling upon speech they find transgressive; they’re just sensitive to different transgressions.”

Posing questions about what kinds of things children should and shouldn’t read is merely the beginning of a conversation about art, the power of literature and the freedom of young people to explore and grow. The instinct to ‘protect’ children from danger is perhaps a natural one; but after decades of experience intervening in local censorship controversies, we can say with confidence that many people, when given a moment to reflect on such questions, are willing to change their minds — or to at least understand that what they consider inappropriate for their own children should not prevent others from reading what they want.

In many cases the impulse to want to censor is just that– a snap judgment. Upon closer inspection, many people decide it’s not such a good idea.