Yesterday we published a post by our Arts Advocacy Program that explored several recent controversies around artwork that addressed the socially volatile issues of police brutality and racially motivated violence. The piece focused on the “culture of outrage” that surrounded each incident and asked what the consequences are for free expression and the health of our public sphere when an artwork is removed, or even destroyed, in response to public pressure.

Yesterday we published a post by our Arts Advocacy Program that explored several recent controversies around artwork that addressed the socially volatile issues of police brutality and racially motivated violence. The piece focused on the “culture of outrage” that surrounded each incident and asked what the consequences are for free expression and the health of our public sphere when an artwork is removed, or even destroyed, in response to public pressure.

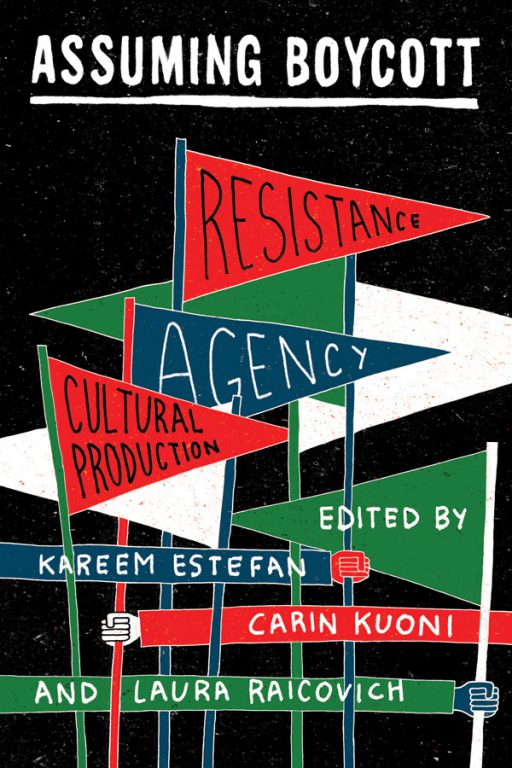

A chapter in a newly released book authored by NCAC’s Director of Programs Svetlana Mintcheva can help elucidate the matter further. The essay, titled ‘Structures of Power and the Ethical Limits of Speech’ can be found in Assuming Boycott: Resistance, Agency, and Cultural Production, a collection of essays exploring the boycott as a “special condition for discourse, artmaking and political engagement” at a time when this form of protest is more prevalent than ever. Specifically, Mintcheva’s essay examines and argues for the value of free expression in light of recent controversies over art and racially sensitive content, as well as over cultural appropriation, which have left people to question the usefulness of an absolutist defense of free speech. As we noted in our blog post yesterday, accusations of cultural appropriation have become commonplace in recent controveries around art tackling a delicate issue.

This was the case with one of the incidents explored in our blog. Los Angeles artist Sam Durant’s controversial sculpture, Scaffold, a wood-and-steel composite of “seven historical gallows that were used in US state-sanctioned executions by hanging between 1859 and 2006,” including executions of Dakota Native Americans, was removed and will be burned in a ceremony overseen by representatives from Native American tribes in Dakota. The destruction of the piece makes a troubling statement about an understanding of who can and should make art about controversial historical subjects, a question Mintcheva broaches in her essay:

In a globally connected world, cultural institutions in the West are increasingly aware that representations of the cultural “other” are often a representation of our own fantasy of the other, and that cultures should be approached as complex systems rather than boutiques of exoticism offering ideas and practices ripped out of their cultural and historical context. But what does such recognition mean in practice? Without attempting to answer a question that calls for a complex process of negotiation rather than a miracle formula, all I would venture to claim here is that we have a serious problem if the awareness of the pitfalls of trans-cultural borrowing is used to demand its absolute prohibition. The exoticizing practices of past cultural appropriation do not justify the erection of an impenetrable fence around cultural traditions (nor would such a feat be possible).

In the case of Durant’s Scaffold, by declaring any other group’s trauma off-limits, protesters have essentially nullified the artists’ liberty to create empathy across identity lines. Indeed, the Mankato Massacre gallows make up only one of the seven executions depicted in the sculpture. This piece engages with the use of capital punishment across race and gender lines – no one given artist could have created it, as the victims hanged on the gallows represented therein include white, black, Middle Eastern, and Native people of varying genders, classes, and political affiliations. And by immediately conceding to the outrage – even going so far as to agree that the work will be destroyed and never re-created – the Walker and Durant have shrugged off the responsibility of hosting a free and open debate about who can lay claim to historical trauma within the scope of art. Rather than opening the topic for conversation, all groups involved here have chosen instead to shut it down.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. In “Structures of Power,” Mintcheva discusses a seperate case wherein Native American students protested an art installation at Santa Barbara City College:

Faced with charges of institutional racism, cultural institutions like the MFA and SBCC—whose predominantly white staffing makes them extremely vulnerable to such accusations—are quick to cancel a project or encourage students to do so. The conversation about the complexities of intercultural borrowing and appropriation usually comes as a coda, following the shamed removal. At best there is a belated nod toward the value of free and open debate. The suppression of a campus art project or a museum event may not seem so significant, but such incidents—watched closely by other cultural actors—are likely to have long-term effects: peer ostracism, or the threat of ostracism, works very efficiently in chilling speech. Criticism is an essential part of cultural production; what is of concern are campaigns against cultural institutions that do not intend to generate a considered conversation around a project, but simply seek to silence it. Such attack campaigns do not present arguments to counter an artist’s concept or debate its implications. They aim to exclude, silence, and blacklist a participant; they present an ultimatum and a demand to censor.

In most of the incidents detailed in our blog, the institutions hosting the work in question have chosen to simply remove– or even destroy– the painting in question, thereby silencing the artist, rather than facilitating any true conversation. As Mintcheva notes, the response to acquiesce to the demands of protestors is understandable given the damage that can be done to a cultural institution labeled as racist. However, while this is the easy route to take, she reminds us the true cost comes later in the form of damage done to the role of a museum in society in an institutions ability to foster a vibrant public sphere:

Cultural institutions play a crucial role in maintaining the openness of social and political debate. That role is threatened if those institutions fail to take on real controversies around difficult and emotionally charged subject matter because some of that subject matter may be offensive or even traumatic. Unless they are prepared to welcome genuine conflict and disagreement, cultural institutions will operate as echo chambers under the pall of a fearful consensus, rather than leaders in a vibrant and agonistic public sphere.

You can read the full essay, ‘Structures of Power and the Ethical Limits of Speech’, here.