The recent rather heavy-handed treatment of Marc Bradley Johnson’s MFA thesis project at New York’s School of Visual Art (SVA) raises some interesting concerns—especially for an institution that aims to play a leadership role in the bio-art movement.

Johnson’s project consists of a refrigerator containing 68 vials of his sperm arranged on a grid. The artist originally intended to give away his semen to any interested member of the public.

Johnson’s project consists of a refrigerator containing 68 vials of his sperm arranged on a grid. The artist originally intended to give away his semen to any interested member of the public.

But SVA, concerned that New York law prohibits the distribution of human tissue outside of a medical facility, confiscated the fridge and planned to dispose of the vials. However, upon further consideration, administrators returned the work to the exhibition but quarantined and sealed the vials in a box labeled ‘bio hazardous waste.’

Were administrators overreacting? Perhaps they were too embarrassed by the work’s content, and the scale tipped over fear of additional complaints that it violated health standards? And what does the bumbling about—to dispose or not to dispose, etc.—say about this institution, which recently launched a bio art lab?

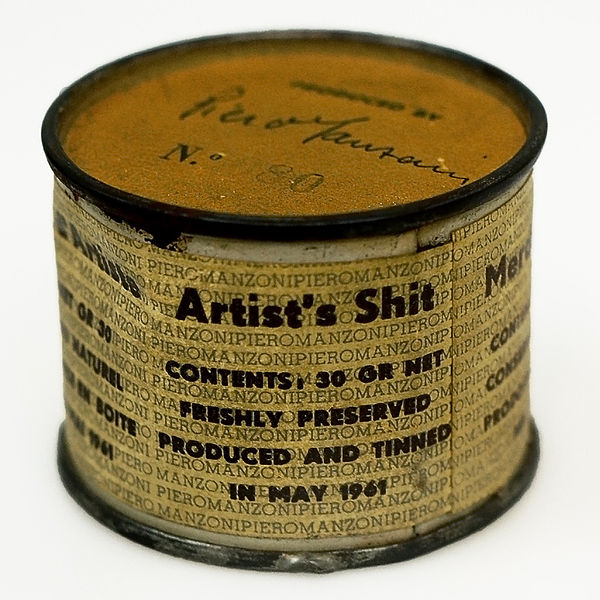

The law that SVA cites as justifying its actions is one that governs reproductive tissue  banks, not art work. The “hazardous” vials (containing microwaved dead sperm ) weren’t offered for their reproductive potential but as a commentary on the value (or lack of value) of artistic activity and what counts as such activity, similar to Pierro Manzoni’s cans of “Artist’s shit” produced a half century ago in 1961.

banks, not art work. The “hazardous” vials (containing microwaved dead sperm ) weren’t offered for their reproductive potential but as a commentary on the value (or lack of value) of artistic activity and what counts as such activity, similar to Pierro Manzoni’s cans of “Artist’s shit” produced a half century ago in 1961.

SVA should have kept Johnson’s work intact but perhaps sealed the fridge and not allow anyone to remove the vials. Adding a bio hazardous waste box didn’t do much for safety— but it did change the very look and message of the piece.

This new message—that bio matter is above all hazardous waste—really interests me, as it poses a threat that, if perhaps someone doesn’t like a piece of bio art, they can always potentially claim it “hazardous.”

As SVA’s own bio art program page explains, “coming to the fore in the early 1990s, bio art is … an international movement with practitioners in such regions as Europe, the U.S., Russia, Asia, Australia and the Americas.” It goes on to describe the sub-genres of bio art as dealing with “molecular and cellular genetics, transgenically altered living matter, reproductive technologies and neurosciences” and including “artists employing biological matter itself as their medium, including processes such as tissue engineering, plant breeding, transgenics and ecological reclamation.”

Certainly, art containing biological materials may raise health concern issues, but shouldn’t an art institution, in this case a pioneer in bio art, work to carve out a space for such practices rather than submit an artist’s work to laws that don’t apply—and to an over-cautiousness that defies common sense?