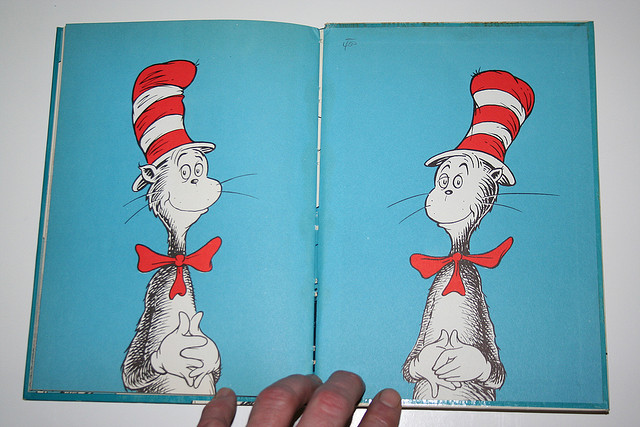

(photo by Daniel X. O’Nell)

March 2 is Read Across America Day, a nationwide celebration in honor of Dr. Seuss’s birthday. Loved all around the world for his colorful characters and unforgettable rhymes, Theodor Seuss Geisel was the author and cartoonist of 46 children’s books, including The Lorax, The Cat in the Hat and How the Grinch Stole Christmas. With four feature films, a Broadway musical, and even a recent Supreme Court opinion mentioning his work, it is difficult to underestimate the timeless cultural significance and legacy of Dr. Seuss.

However, Dr. Seuss was not always so appreciated. In fact, his work has been challenged, censored and banned numerous times.

Before he became a children’s book author, Geisel published over 400 political cartoons for the New York newspaper PM during World War II. As the chief editorial cartoonist, Geisel used his column to mock isolationists, fascists, and even fellow Americans who discriminated against African-Americans, at a time when such racism was all too common. Geisel continued to express his political views in the post-war era through books such as Horton Hears a Who! (1954), written after a 1953 visit to Japan. In the book, the Whos are inhabitants of a planet threatened with annihilation unless others, like the protagonist, Horton, stand up for them—a clear reference to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although the oft-quoted line, “A person’s a person, no matter how small,” reflects the author’s overall message of compassion, Geisel’s politically charged books have sparked a number of controversies over the years.

Yertle the Turtle (1958), for instance, is about a tyrannical turtle who builds his throne on the backs of suffering others–an allegory to the autocratic regime of Hitler. Mack, the turtle at the very bottom of the pile Yertle is standing on, asks several times for a respite, but the king just silences him. In the end, no longer able to withstand the pain and hunger, Mack topples the dictator, proclaiming, “all the turtles are free / As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.” In 2012, however, Prince Rupert School District in British Columbia, Canada, deemed the book too political for children and removed the book from schools. The line, “I know up on top you are seeing great sights, but down here at the bottom, we too should have rights,” supposedly violated a school ban on political messages. It was over a year later that the grievance was settled between the teachers and the school board, and the book was returned to classroom shelves.

Meanwhile, Green Eggs and Ham (1960), a book that encourages kids to try new things, was banned in the People’s Republic of China almost as soon as it was published. In Maoist China, it was forbidden to read the book because its mantra, “I do not like like them, Sam-I-am, I do not like green eggs and ham,” was considered to be a commentary on Marxism. The Chinese government suppressed the book for decades until the author’s death in 1991, after which the ban was lifted.

Finally, perhaps one of the most blatant of Dr. Seuss’s works is The Lorax (1971), a book that reflects Geisel’s pro-environment stance. The Lorax is a fuzzy, charismatic woodland creature who speaks for the trees because the trees have no tongues. In the book, a character called the Once-ler cuts down the Truffula Trees against the pleas of the Lorax in order to make a garment called Thneed. Later, the Once-ler repents for his actions that polluted the environment, destroyed the forest, and drove away the Lorax and the animals. “Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack,” mourns the Once-ler, “Then the Lorax / and all of his friends / may come back.”

Unfortunately, parents in logging communities were very upset by the book and complained that it criminalized their industry. In 1989, Laytonville Unified School District in northern California axed the book from required reading lists. The National Oak Flooring Manufacturers Association has even published its own pro-logging rebuttal, called “The Truax.” According to the American Library Association, The Lorax has been one of the most challenged and banned books in the country.

In an essay published in 1960, Geisel observed that “writers are beginning to realize that books for children have a greater potential for good or evil than any other form of literature on earth.” He believed in teaching children to challenge authority and not just to model good behaviour, and he even called himself “subversive as hell.”

On the occasion of his 111th birthday, NCAC celebrates not only Dr. Seuss’s powerful books, but also those who stood up against the censors that tried to keep everyone from enjoying them.