Reprinted with permission from ACLU Ohio. Read original here

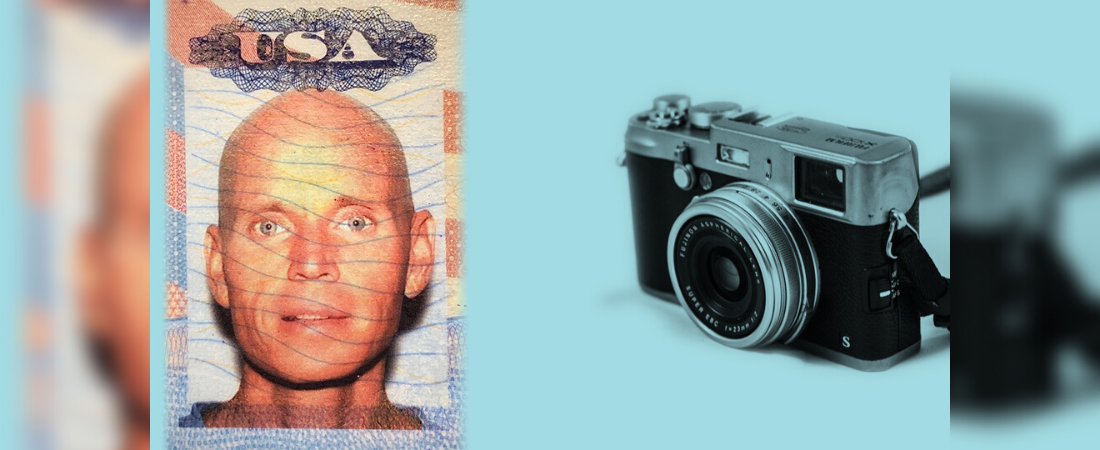

Photographs and the First Amendment. My Harrowing Journey Through U.S. Customs

by Tim Stegmaier

In the United States, people are allowed to carry a loaded gun capable of mass killings, but I was treated as a criminal for carrying a camera with the intention of helping people.

I am an independent photographer, artist, and journalist. For over thirty years, I’ve traveled around the world capturing images of culture and the human condition, and self-published 12 books of photography on subjects ranging from yoga, to animal conservation, to daily life in China, southeast Asia, Guinea, and Senegal. My work has been published by National Geographic and exhibited globally in art museums and galleries.

Earlier this year, my photojournalism work took me to the Philippines. Walking through the poorest neighborhoods of Manila, I was struck by the dire, heart-wrenching conditions of a neglected population. Currents carry mountains of plastic and industrial waste from Manila Bay and the Pasig River to form toxic cesspools near the Tondo and Baseco neighborhoods, laden with animal and human fecal matter. People have to live from this “dead” water, whether catching something to eat for the day or salvaging items from it to attempt to sell for a living.

For the record, it’s not uncommon in developing areas of the world to see young children unclothed in the streets.

But these children were swimming in toxic water and industrial waste, exposing themselves to cholera, typhoid fever, and other infections. Their parents allow it, even remarking that “we are going to die anyway, so what’s the difference?”

I took hundreds of candid pictures—street style; I posed nothing. Children I met would strike poses of their own when they saw my camera, smiling even in their grim surroundings. Sharing these images will be my way of pleading for help for a community that desperately needs medicine, education, and basic infrastructure. If the world takes notice, perhaps I can help make positive changes.

When I flew home, U.S. Customs and Border Protection detained me—with no explanation.

CBP pulled me aside after a 13-hour flight from Shanghai to Detroit, on my way home to Ohio. No one would tell me why they flagged me, and I still don’t know, but they asked to search my computer. It is possible that I could have avoided five months of psychological stress with three words: GET A WARRANT. But I was sleep-deprived, and innocent of any crime. So I let them. They took my phone, so I couldn’t let my waiting family know why I had missed my connection and wasn’t there when they came to meet me in Cincinnati. It was four hours before I was offered water to drink.

It was another half-hour before an agent read me my Miranda rights. Then he asked me if I had sex with children while I had been abroad.

“What are you doing here?” The agent knew that I was an American citizen, but I had to explain why I was coming to my own home country. I told him I was going to Cincinnati. “After that, where are you going?” I explained I was going to Dallas to meet with my wife, who was doing a training for Montessori education. He seized on that. “Does she teach children?” No, I explained. She teaches adults who teach children. “So why are you going to Dallas?” To be with my wife, and to photograph while I was there. His eyes widened when I said that, as though I had admitted to some kind of suspicious behavior.

I tried to explain the work that I do. They looked skeptical at my simple point-and-shoot camera, and told me I should have papers showing that I was a “real” photographer. They compared my images with drugs, as though I were smuggling contraband into the country. I was told that I should “learn a lesson” and “consider myself lucky,” because the supervisor believed me just enough not to lock me up.

When they were done, they kept my computer, my camera, and my smartphone, and the tens of thousands of photographs on them. Not just those from Manila, but also irreplaceable life moments with my wife and family.

Without my equipment or pictures, I was forced to halt my work. I had given my word to meet publication deadlines, but was suddenly unable to meet them. Over a month later, I finally received an official Notice of Seizure telling me that my equipment had been seized because it contained “visual depictions of sexual exploitation of children.”

To be accused of being associated with child oppression makes me physically ill. I am a professional photographer. This is my art, my work, and my life.

Lawyers from the ACLU of Ohio wrote a formal petition to CBP on my behalf. They explained that my work is valuable artistic expression, and protected by the First Amendment. Seizing my equipment was a violation of my constitutional rights. The National Coalition Against Censorship, along with the ACLU and other artistic and free-speech advocates, submitted another letter urging CBP to return my equipment.

Three months after they seized my equipment, CBP finally admitted there was nothing wrong with the pictures.

CBP promised to return my equipment, but only if I signed a release disclaiming my right to sue them for the wrongful detention and seizure. If I didn’t sign it, they said, I would have to go through a formal hearing process that could take many more months.

I made arrangements to pick up my equipment when I next passed through the Detroit airport. Incredibly, CBP stopped me again, and again they asked to search my belongings. I still don’t know why. Luckily, I carry the ACLU’s petition letter with me, right next to CBP’s letter admitting I did nothing wrong. I showed these letters to them, and eventually they let me go.

This time, when I left, I took all my equipment and all my pictures with me.

Freedom of expression, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press are not exclusive to America. These virtues speak to the fundamental nature within all human beings. The U.S. constitutional rights have worldwide appeal, because they contain the universal respect for the life-given Human Constitution that resides in us all. But those rights, these virtues, are under constant assault, now as much as ever. They must be defended, every single day.

I dream of a world where pictures for social change are no longer necessary. But until then, I will continue to do my work: to give voice to people like those children in Manila. I hope now that their voices will be heard.

I am incredibly grateful for the ACLU of Ohio’s timely intervention into this situation. Without guardians of our individual rights my work, my pictures, and the chance to help those children in Manila might have been lost forever.