(Note: Read or download this resource as a PDF file)

(Note: Read or download this resource as a PDF file)

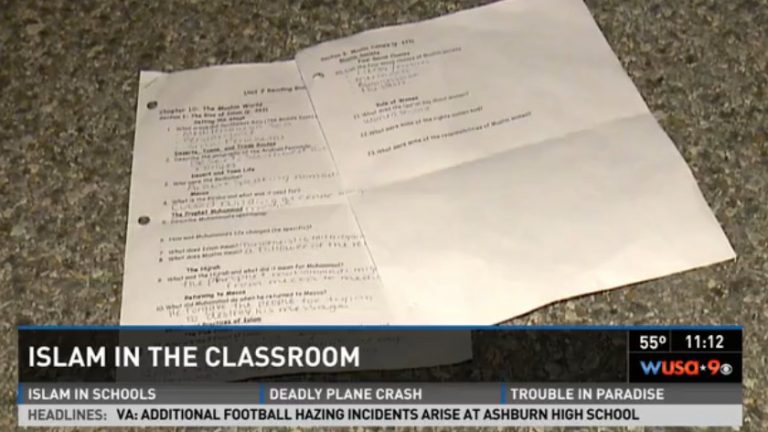

A rising grassroots movement is seeking to restrict how Islam is discussed in textbooks and other public school curricula. These campaigns, which often appear to be fueled by undisguised Islamophobia, misrepresent teaching about religion as indoctrination into a religion, misunderstand the imperatives of the First Amendment, and threaten the integrity of the public education system.

A number of incidents have been reported around the country, some of which may be connected to national organizations. The conservative American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ) claims there is “a nation-wide epidemic” of Islamic “indoctrination” in public schools, some of which it deems unconstitutional. It singled out a chapter in a 7th grade Tennessee study guide called “Origins of Islam.” The group is active in cases in Wisconsin, Georgia, and California, and its “Stop Islamic Indoctrination in School” petition has over 200,000 signatures. Another group, ACT! For America, has inspired local groups to challenge history textbooks; in March of this year, activists filed formal complaints about two textbooks in Charlotte County, Florida, claiming that they whitewash Islam.

Some government officials are getting involved. In Tennessee, Rep. Marsha Blackburn declared in September that it “is reprehensible that our school system…is more concerned with teaching the practices of Islam than the history of Christianity.” The following month, Republican state representative Sheila Butt introduced a bill that would prohibit schools from teaching about “religious doctrine” until 10th grade. The Tennessee Department of Education is planning to review its history curriculum in January 2016. And protesters in Walton County, Georgia claimed that 7th graders were being “indoctrinated” into Islam in a world history class. While educators explained that state standards required students to describe the cultures and religions of the Middle East, the Department of Education removed a program guide called “Respecting Beliefs” that was part of its statewide middle school requirements.

While parents and community members have every right to voice their opinion about curriculum, most of these efforts reveal a fundamental misunderstanding about some Constitutional principles:

Learning about religion does not violate the Establishment Clause The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits the government from favoring or disfavoring any particular religion or religion in general. It does not prohibit public schools from teaching about religion, when this is presented “objectively as part of a secular program of education,” as the Supreme Court stated in Abington v. Schempp (1963). The academic study of religion—whether historical, literary, or cultural—is designed and intended to encourage awareness and information, not acceptance or devotion.

Curriculum and teaching decisions must be based on pedagogical reasons, not religious opinions. In the words of A Teacher’s Guide to Religion in the Public Schools, which has been endorsed by leading educational and religious associations including the National PTA and the Christian Legal Society, “[t]he academic needs of the course determine which religions are studied.”

Religious freedom does not mean freedom from information. Parents do not have a constitutional right under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to prevent public schools from presenting educationally valuable material that conflicts with their religious beliefs.

Removing books because of their content is unconstitutional. In all areas of instruction, including the teaching of material about or referring to Islam, public schools are required to respect basic First Amendment principles: Books or any other educational materials may not be removed simply because of disagreement with the ideas contained in those materials or so as to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion’.” Pico v. Island Trees (1982)

Students have the right to express their beliefs, including their religious beliefs, at school when students are asked or permitted to express personal views on the issue. Although public schools may not endorse or reject particular religious ideas, students are free to express their own views in various contexts, as long as doing so does not interfere with the educational program. According to guidelines published by the U.S. Department of Education, students “may express their beliefs in the form of homework, artwork, and other written and oral assignments free of discrimination based on the religious content of their submissions.”

Religious literacy matters. According to the American Academy of Religion, religious literacy includes “the ability to discern and explore the religious dimensions of political, social and cultural expressions across time and place.” Religious beliefs and practices shape events at home and abroad. In a diverse democracy and in an interconnected world, religious literacy is crucial to responsible citizenship and sensible public and foreign policy.

Americans need more religious literacy, not less. Surveys by Pew Research Center show that although six in ten U.S. adults say that religion is very important in their lives, many lack basic understanding of the world’s major faiths. Roughly half of Americans do not know that Joseph Smith was Mormon, that the Dalai Lama is Buddhist, or that the Quran is the Islamic holy book.

School and government officials should be mindful of these principles in responding to complaints about the teaching of Islam.

(To see a list of recent cases, read “Islam: Indoctrination or Education? A Timeline“)