(Note: A version of this piece appeared in the Denver Post, 3/25/16)

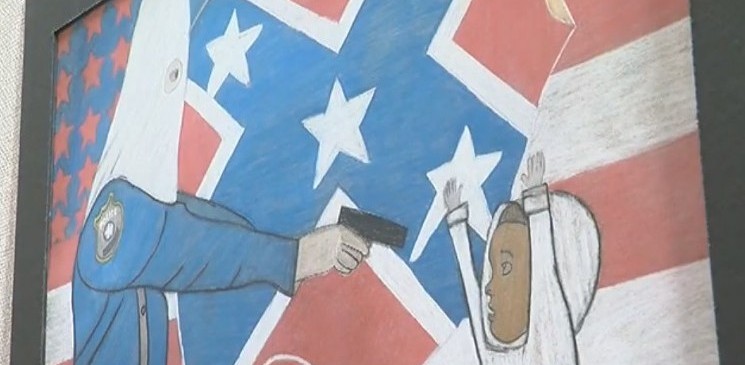

Does art that offends belong in a government building? That’s the debate unfolding in Denver, after a student’s painting that likens police to the Ku Klux Klan was displayed in the city’s Webb Building.

There are some fundamental free speech principles for all to consider.

Around the country, many artists have responded to current events by creating works condemning police brutality and racial profiling. While most people would say they agree with an individual’s right to creative expression, things get a little more contentious when such works are displayed in public. The display of such work — sometimes in a library or at a high school — is regularly followed by calls for removal, often from the law enforcement community.

Surely, police officers who risk their lives to protect the rest of us may be offended at such representations. But in our society, there is no right to not be offended, especially for those in public service, who should be open to critique by the community they serve.

The calls to remove the painting at the Webb Building — which has since come down at the student’s request — were not surprising. We were told that there were “concerns from the community” being raised, and that the piece being shown in a government building lends it a “legitimacy” that it does not deserve.

These complaints raise a fundamental question about where we draw the line. When is a piece so inflammatory that it should be removed from a city building? While there are legal limits to the kind of speech protected by the First Amendment — including exclusions carved out for speech that directly incites violence, for defamation, obscenity and a few other narrowly defined categories — feeling offended, no matter how deeply felt the offense, is not one of those categories.

In a call for dialogue, Mayor Michael Hancock and acting Denver Public Schools superintendent Susana Cordova released a statement saying they “absolutely value the voices of our young artists,” and that they “also greatly respect the impact this art has had on our officers who serve and protect Denver.”

Such a discussion should include the promotion of basic free speech principles. Shouldn’t we, as a society, encourage a young person to actively engage in political debate? Don’t we sorely need to nurture engaged citizens who feel free to question the tactics of law enforcement and the workings of government?

These are all questions to consider before pressuring a student to take down a work in which they have clearly poured their anger and pain.