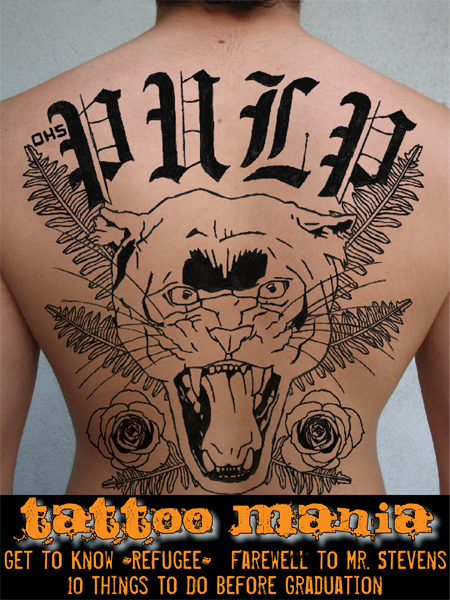

Two weeks ago in a round-up of tales of student press censorship around the nation, we mentioned the case of PULP magazine, a publication produced by a journalism class at Orange High School. Just a recap of the highly sensitive items that raised red flags for the school’s, principal, SK Johnson: a Top Ten list that playfully advocates skinny-dipping and cutting school (the magazine is willing to concede this piece), but more so, the cover of the magazine which corresponds to a feature on tattoos and uses what the principal considers to be a “gang-looking” font. The dangerous font is the historical Old English typeface that is also often affiliated with Goth culture and newspaper mastheads. The latest is that all 300 copies of the magazine are still sitting in Johnson’s office. On Monday, Johnson told the local newspaper, the OC Register, that he has not decided what to do with the magazines (“I haven’t given it too much thought.”)

Two weeks ago in a round-up of tales of student press censorship around the nation, we mentioned the case of PULP magazine, a publication produced by a journalism class at Orange High School. Just a recap of the highly sensitive items that raised red flags for the school’s, principal, SK Johnson: a Top Ten list that playfully advocates skinny-dipping and cutting school (the magazine is willing to concede this piece), but more so, the cover of the magazine which corresponds to a feature on tattoos and uses what the principal considers to be a “gang-looking” font. The dangerous font is the historical Old English typeface that is also often affiliated with Goth culture and newspaper mastheads. The latest is that all 300 copies of the magazine are still sitting in Johnson’s office. On Monday, Johnson told the local newspaper, the OC Register, that he has not decided what to do with the magazines (“I haven’t given it too much thought.”)

Of course Johnson hasn’t given the matter too much thought. It’s the close of another school-year. Johnson is deploying the age-old school administrator tactic of “waiting out” the controversy. He figures that either the issue will grow stale or the seniors on the magazine staff will graduate. This is exactly the problem with prior review – the irreparable harm is that news that is censored is not worth the paper it’s printed on a few days later. This is why the First Amendment places a huge constitutional burden for a party seeking prior restraint to bar a publication from printing contested speech (President Nixon was unable to meet this burden in his effort to enjoin The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing the famous Pentagon Papers.) In the school context, unfortunately, student journalists are often at the mercy of a censor board of one — the school principal. This easily allows for an abuse of power.

And make no mistake Principal Johnson’s injunction lacks justification. It is likely in violation of California laws on student speech. Johnson’s interest in keeping the magazine out of circulation on account of a font is not as compelling as say the concern for protecting another student’s privacy or a defamation claim. Nor does confiscating the magazines solve any problems the school might have in dealing with gangs. In his official comment on his position, “I haven’t given it too much thought,” Johnson conveys an utter disrespect for the time and work the students put into the magazine. The thing that administrators such as Johnson forget is that they may try to stifle speech that “bears the imprimatur of the school” but they can’t curb speech in the hallways. What students at Orange High will note from the case of PULP magazine is not that gangs are bad but that their school principal is an arbitrary decision-maker who censored their peers over a font.