Sex. It’s impure, shameful, dirty, immoral, and… harmful? Taboos around sex have existed through the ages, so much so that the American legal system classifies obscene sexual material as a rare exception to First Amendment protection. We rely on judges to tell us if our sexual imagination is obscene or acceptable, and 41 years ago this month, the Supreme Court handed down a decision in Miller v. California which signaled a restrictive approach to free speech rights, and which compelled a group of First Amendment advocates to launch what became the National Coalition Against Censorship.

The Miller decision invited renewed attacks on explicit material in literature, art, film, music, magazines, and video – any cultural medium using words or images that could offend the community’s notion of what is “patently offensive.” But the application of the Miller test has always been subjective and arbitrary, hardly an improvement on Justice Potter Stewart’s famous test: the “I know it when I see it” rule.

What was taboo in the ’70s could hardly be labeled obscene now. The once-sensational sex talk in “Carnal Knowledge” is relatively common in film today. Did anyone think that the homoeroticism in Robert Mapplethorpe’s prosecuted exhibition in the early ’90s would appear in magazines in the 21st century? So what’s still taboo? Masturbation? Bestiality? Below, NCAC takes a look at the obscene over our four decades and beyond. No trigger warning necessary: the following examples are not dangerous. Disgusting? That’s for you to decide.

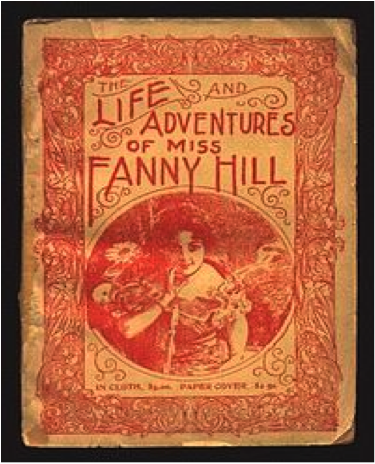

Blame John Cleland, author of Fanny Hill. The title character’s chronicles of sexual activity as a London prostitute initiated the first obscenity case in the United States when a Massachusetts court convicted a publisher for printing the “lewd” book in 1821.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the D.H. Lawrence classic, was another British import that faced U.S. obscenity prosecution more than a century after the Fanny Hill case, because of its story of extramarital sex and use of words like “cunt” and variations of “fuck.” The Supreme Court lifted the ban on Chatterley in 1959, and the sexual revolution that began in the ’60s changed notions about the “desperate passion of the forbidden”:

Mike Nichols’ 1971 film Carnal Knowledge exemplifies the changing moral values of American society, when candid sexual banter was no longer seen as verboten. The Supreme Court found that the film was not “patently offensive,” but that was only after some theatre managers were prosecuted for screening the movie in which Jack Nicholson boasts of his sexual conquests:

As gay sexuality and its acceptance in American culture evolved in the ’70s and ’80s, so did attempts to label it as obscene, rather than “artistic.” Shown below is an image from Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Perfect Moment photo exhibit, which spurred prosecution in 1990 for its sadomasochistic images:

Today, you can turn on the T.V. and find rubber men as series regulars:

However, films that dared to depict sexual acts involving minors faced much greater legal scrutiny. In the 90s, prosecutors targeted (ultimately unsuccessfully) Passolini’s film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, and the adaptation of Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, both of which depicted underage sex. Although Passolini intended the film as an attack on political corruption and abuse of power, Salò was poorly understood and is remembered by many for its depictions of torture and rape and “cockmongers”:

Now, obscenity law still discriminates against sexual expression – even a drawing of an imaginary act. However, can a drawing, no matter how despicable the act it portrays, cause “harm”? How can a story or a picture, voluntarily viewed by adults, be more destructive of the moral fiber of the universe than one’s 2am sexual fantasy (enacted in the privacy of our brains)?

Yet, in 2010, Christopher Handley from Iowa served a jail sentence for possessing manga, a recognized Japanese cartoon art form, depicting highly stylized “drawings of children being sexually abused.” Purveyors of commercial porn are regularly prosecuted, even though the enormous U.S. porn market suggests that community values are perfectly fine with sex of any kind.

Some groups, like the American Family Association, rely on obscenity law to demand the removal of artwork with partial nudity. They have not succeeded, but once you have a law which criminalizes sexual expression just because it could be seen as offensive, no material is completely safe from attack.

The relaxation of legal restrictions on adult access to sexual content hasn’t eliminated the censorship of sex, although it now looks different than it did in 1974 when NCAC was founded. The cultural anxiety about sexual expression, which once took the form of battles around books like Lady Chatterley’s Loverhasn’t gone away. As our conceptions of “disgust” evolve, it is just manifested differently. Is there any form of sexual expression that you find personally revolting, and if so, do you think it should be censored?

Tell us in the comments section below.