Marta Minujín's The Parthenon of Books at documenta 14 in Kassel, Germany. Photo: Sheryl Oring

Books play a starring role this year at documenta 14, the exhibition of contemporary art that takes place every five years in Kassel, Germany. On Friedrichsplatz, the square in front of the Fridericianum (documenta’s central exhibition site), visitors are confronted with a life-size replica of the Parthenon, but instead of marble, the structure is composed of 100,000 banned books. The installation, by Argentinian artist Marta Minujín, is intended as a means to stir up discussion about censorship.

The Parthenon of Books was created with the help of public donations of books, and is Minujín’s second iteration of this work; the first, El Partenón de libros, was installed in Buenos Aires in 1983, and utilized books banned by Argentina’s military junta.

Marta Minujín's The Parthenon of Books at documenta 14 in Kassel. Photo: Sheryl Oring

Friedrichsplatz is the site where, on May 19, 1933, the Nazis burned some 2,000 books by Jewish and Marxist authors, an important detail that may escape many of the estimated one million visitors to this year’s art extravaganza. The Kassel book burning was one of dozens of such events that took place shortly after Adolf Hitler took power. The actions began in Berlin, where students from the Humboldt University gathered books by “undesirable” authors and burned them in a festive event on Bebelplatz.

Minujín's Parthenon is a skeleton-like structure of metal wire that houses the books, which were inserted and then covered in plastic. Photo: Sheryl Oring

Minujín began collecting books last fall at the Frankfurt Book Fair, working from a list of around 170 titles that have been banned in the past or that are currently disputed. Authors range from Karl Marx to J.K. Rowling, John Steinbeck to Sigmund Freud, and include Austrian novelist Vicki Baum and German playwright Bertolt Brecht, two writers whose books were burned during the Nazi period. Meanwhile, coordinating with the project, students at the University of Kassel are working with their professors to create a list of banned books from around the world. To date, more than 70,000 titles have been added to the list.

Maria Eichhorn's work at documenta includes a variety of works that call attention to the expropriation of property from European Jews.

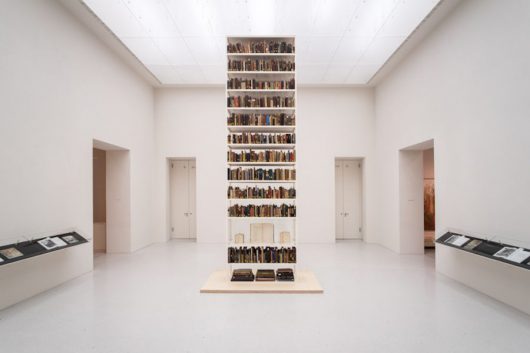

Books are also the centerpiece of a work by German artist Maria Eichhorn. Situated a few blocks away from Friedrichsplatz at the Neue Galerie is documentation of Eichhorn’s Rose Valland Institute, named after the art historian Rose Valland who secretly documented Nazi art theft during the German occupation of Paris. In the spirit of Valland, the institute "researches and documents the expropriation of property formerly owned by Europe’s Jewish population and the ongoing impact of those confiscations." For documenta, Eichhorn issued an open call inviting the public to research Nazi looting of inherited property and submit findings to the Institute.

The nine-part installation includes photographs of furniture and household items the Nazis stole from Jews in Paris, as well as extensive documentation of the confiscation of assets and art once owned by Alexander Fiorino, a well-respected banker and art collector in Kassel. These documents ring the walls of a large room, where a towering bookcase—titled Unlawfully acquired books from Jewish ownership—stands in the center. It holds books that were confiscated from Jews and then acquired by the Berliner Stadtbibliothek (Berlin’s city library) in 1943; they are registered with the letter “J” for Jew, indicating that decades of librarians knew of their origin.

A journalist friend who visited documenta just days ahead of my trip recommended that I stop by Eichhorn’s work. “It’s not art per se, but I learned a lot of new things there,” he said. But in the land of Beuys, where everyone is an artist, the question is not whether the work is art, but why, nearly seven decades after the end of World War II, it falls to artists to engage the questions that Eichhorn raises in her work.

Not far from the Neue Galerie is Grimm World, a sparkling new museum that “offers insights into the life and work of the Brothers Grimm.” The permanent exhibition offers extensive documentation of the Grimm’s life work on their German Dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch). The brothers, known for their dark fairy tales such as Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel, painstakingly created entries for the comprehensive dictionary of the German language that set the national standard since the mid-nineteenth century. Some 600,000 small paper source notes were at the heart of their work.

Regina José Galindo's El objectivo (The objective). 2017. Performance in chamber with four G36 assault rifles.

As I moved down the documenta path, one of my last visits was to the City Museum of Kassel. I left the Guatemalan artist Regina Jose Galindo’s installation El objectivo (The Objective)—Galindo is closed off in a room where visitors can only see her by looking through the gunsite of an assault rifle (the public may take the place of the performer if she is not performing)—and headed out through the museum’s permanent exhibition “War and Peace.” At the center of the first exhibition room is a large model of the city showing the empty shells of buildings that remained after extensive bombing by British and American forces toward the end of the war. Surrounding the model are cases with information on the bombing that destroyed nearly 80 percent of the city.

In the next room, in a small corner case, is a star made from yellow cloth, the identification Jews were required to wear during the war. The juxtaposition of this small case representing the persecution of the Jews during World War II installed amidst an entire floor dedicated to documenting the destruction of Kassel by the Allies again begs the question: Why are contemporary artists the ones raising issues about art, antiques, and other belongings stolen from Jews across Europe? Why is it that seemingly only artists are engaging the issue of the stolen Jewish-owned books that remain in respected public libraries—the same libraries in which the Grimm’s celebrated dictionary and the notes that led to its creation are also housed? Why are the questions about these remnants of daily life and the lost inheritance of current and future generations of Jews left to artists like Eichhorn to give them life and visibility on a public platform?

Back at Friedrichsplatz, construction on the Parthenon continues as the artist collects the last books needed to complete the work. Once it is finished, an action is planned where the books will be distributed to the public. Again, the artist is at the heart of the action that invites us to reflect, and perhaps—just perhaps—to act.

This article was contributed by artist and NCAC correspondent-at-large Sheryl Oring.