As the rest of the world is off celebrating May Day–recognized as International Workers Day in many countries–here in the United States we are celebrating… Loyalty Day?

All quite curious, as the modern May Day holiday started as a commemoration of an event in the United States: The Haymarket demonstrations in support of a eight-hour working day in Chicago in 1886, and the subsequent execution of anarchist trade union organizers framed on false charges of throwing a bomb at police breaking up the demonstration.

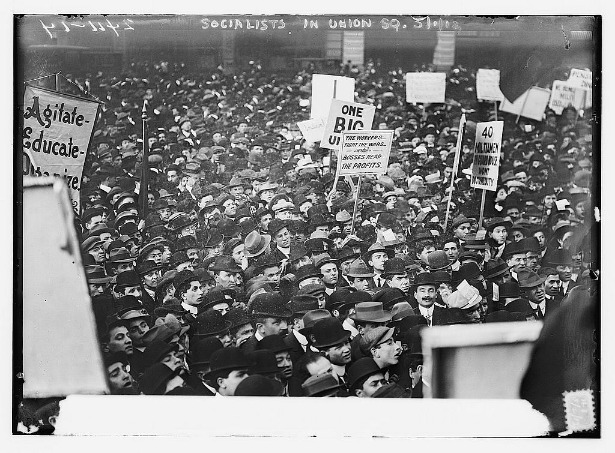

In 1889, the first Congress of the Second International, meeting in Paris for the centennial of the French Revolution, called for international demonstrations on the 1890 anniversary of the Chicago protests. Recognized worldwide today, May Day was formally recognized as an annual event at the International’s Second Congress in 1891.

Right-wing governments have traditionally sought to repress the message behind International Workers’ Day, with fascist governments in Portugal, Italy, Germany and Spain abolishing the workers’ holiday.

So how did we end up with “Loyalty Day”? In 1921–following the Russian Revolution and in the midst of the Red Scare–a nationwide hysteria provoked by a mounting fear that a Bolshevik revolution would overhaul “the American way of life,” May 1st was promoted as “Americanization Day.” In 1949, Americanization Day was renamed Loyalty Day; in 1958, Congress declared it an official holiday.

The contrast between a worldwide celebration of labor and the U.S. celebration of loyalty to the country, however, has sinister overtones. The launch of Loyalty Day in 1958 came in a period where cultural workers were routinely investigated and blacklisted for being suspected of disloyalty. Indeed, loyalty oaths–required from government employees during the 1940s and becoming widespread in the 1950s–and the Congressional hearings chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy helped sustain Cold War fear and suppression of any ideas deemed critical of U.S. capitalism.

In a country which appears systematically hostile to any celebration of labor and the history of its struggles, the failure to celebrate May Day is a reminder of the persistence of the mindset that prevailed during some of the darkest days of American censorship.