In 1993, NCAC convened a conference titled The Sex Panic: Women, Censorship, and "Pornography," to challenge "the myths that censorship is good for women, that women want censorship, and that those who support censorship speak for women." Two decades later, we wonder if there’s a new sex panic taking place in academia, as sexual expression is once again under attack as harmful to women, and possibly as a form of sexual harassment.

In 1993, NCAC convened a conference titled The Sex Panic: Women, Censorship, and "Pornography," to challenge "the myths that censorship is good for women, that women want censorship, and that those who support censorship speak for women." Two decades later, we wonder if there’s a new sex panic taking place in academia, as sexual expression is once again under attack as harmful to women, and possibly as a form of sexual harassment.

Veteran LSU professor Teresa Buchanan was fired in June over off-hand comments and jokes with sexual overtones which "disturbed' some who heard them. A faculty committee reviewed the case and declared that Buchanan’s removal was not warranted. But LSU president F. King Alexander dismissed her nonetheless, claiming in public statements that her speech constituted sexual harassment.

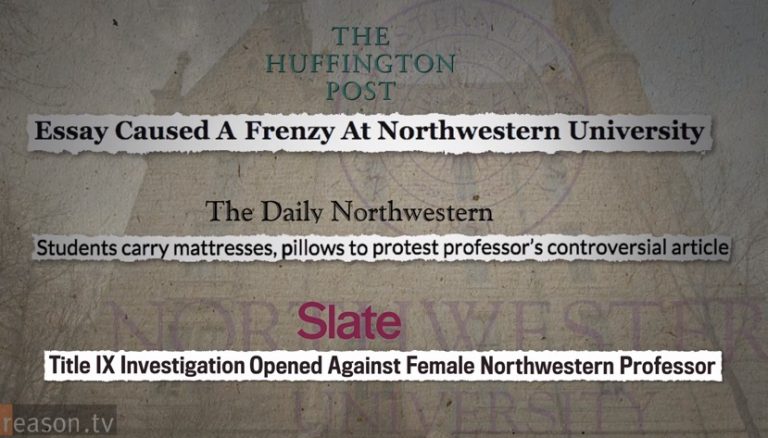

Buchanan is hardly alone. In 2014, professor Patti Adler was investigated for sexual harassment at the University of Colorado over a classroom exercise in which students participated in role-playing skits as prostitutes. More recently, Northwestern professor Laura Kipnis published an article, "Sexual Paranoia Strikes Academe," that prompted a Title IX complaint from two students alleging that it created a hostile environment.

In fact, any mention of sexual issues may expose professors to scrutiny – and pressure. Alice Dreger, professor of bioethics at Northwestern, resigned from the university over the censorship of the academic journal Atrium, which she guest edited. The Winter 2014 issue, Bad Girls, addressed “pervasive cultural myths” about women’s behavior and notions of femininity. It included a piece called "Head Nurse," in which Syracuse professor William Peace recounted his anxiety, as a recently-paralyzed 18 year old, over whether he would regain sexual function. A nurse in a rehabilitation facility reassured him by, among other things, performing oral sex – an act that he found profoundly compassionate and reassuring, and for which he remains grateful.

While the subject matter alone is certainly provocative to some, the piece is a thoughtful, poignant examination of recovery, sexuality and the rehabilitative process. The university thought otherwise, and promptly took down Atrium’s entire archives. To contain any supposed damage to the school’s “brand,” school officials reportedly sought to institute a pre-publication review process. As Dreger noted in her resignation letter, the battle over censoring Atrium came just as she was finishing "a book about academic freedom that focuses particularly on researchers who get in trouble for putting forth challenging ideas about sex."

Forget, for a moment, student demands for trigger warnings. We may have an even bigger problem if there’s a new sex panic on campus, fueled jointly by activists with very different concerns. It wouldn’t be the first time odd bedfellows joined forces to attack sexual expression. Not long ago, pornography was attacked as harmful to women by feminists like Catharine MacKinnon, evangelical Christians like James Dobson, and the government in the form of Attorney General Ed Meese. They did not succeed – ultimately the First Amendment prevailed. But in Canada, where the anti-pornography law overrode speech protections, it was enforced against feminist and gay bookstores.

As feminists, we need to be careful what we wish for – and whom we entrust to “protect” us.