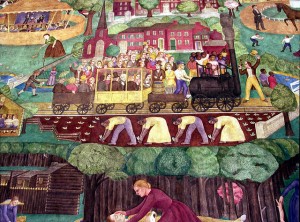

UPDATE 4/21/2017: Victory! The controversial mural depicting scenes of African-Americans picking tobacco and black musicians entertaining white dancers has been uncovered at the University of Kentucky after over a year of being shrouded. The painting will now be displayed with a sign that provides context around the work.

The mural, a Public Works project from 1934, was censored in late 2015 after complaints from African American students who felt the work's depiction of slavery was demeaning.

At the time, NCAC urged the university to preserve the mural and continue to display it with added information that places the mural "within a broader context of the state’s and the nation’s history of slavery."

We applaud the university's decision.

Original post:

After students of color at the University of Kentucky objected to a 1934 mural in the University’s busy Memorial Hall, the administration draped the work in white fabric—and at least one layer of unintentional irony.

The 38 x 11 foot fresco depicting Kentucky history, created by UK alumna Ann Rice O’Hanlon as part of the Public Works of Art project, includes scenes of African-Americans picking tobacco and black musicians entertaining white dancers.

In a November 23 statement issued two weeks after a meeting with two dozen African-American students, University President Eli Capilouto related the comment of one student that “each time he walks into class at Memorial Hall he looks at the black men and women toiling in tobacco fields and receives the terrible reminder that his ancestors were enslaved, subjugated by his fellow humans.” Worse still, Capilouto added, “the mural provides a sanitized image of that history. The irony is that artistic talent actually painted over the stark reality of unimaginable brutality, pain, and suffering.”

Capilouto reported that he had “begun discussions with facilities administrators and respected campus leaders in the arts and history” to find a way to “respond to the pain that it causes and bring sober reality to its romanticized depiction of our history” while remaining “respectful of every perspective.”

In the meantime, the Memorial Hall mural will be shrouded.

Historical murals have often been the site of controversies. In the same year that O’Hanlon’s fresco was completed, workers in the lobby of Rockefeller Center demolished Diego Rivera’s unfinished Man at the Crossroads after it was attacked for promoting anti-capitalist ideology.

More recently, NAACP representatives in Jefferson County, Alabama have called on the County to remove from its courthouse two 1931 John W. Norton murals, one of which show slaves working in the fields beneath plantation owners on horseback. Another debate surrounds a portrait of early Idaho life in a public building in Boise, Idaho that includes the lynching of a Native American man.

Some proponents of preserving such murals argue that they can initiate important reflections on the past. As Janet Gallimore, director of the Idaho Historical Society, told a Spokane newspaper, “History gives us context. It gives us the opportunity to think and learn and to not necessarily repeat the mistakes of the past, so to the extent that we can use these murals as an educational opportunity and an opportunity for dialogue, that’s a good thing.”

Conversations about history are never just conversations about what happened; they are also conversations about how we talk about what happened. In the case of Ann Rice O’Hanlon and her muralist peers of the 1930s, there is much to talk about.

The poet and essayist Wendell Berry, a relative of O’Hanlon’s, suggested in an op-ed that her inclusion of slavery in Kentucky's history in 1934 must have taken some courage: "The uniform clothing and posture of the workers denotes an oppressive regimentation. The railroad, its cars filled with white passengers, seems to be borne upon the slaves’ bent backs." A 1964 oral history interview with O’Hanlon provides some evidence for the complexity of her own racial attitudes.

President Capilouto’s statement exhibits an ironic tension between two impulses: the impulse to remove from view the wrongs of the past so as to protect a young generation of students from experiencing the pain of history, and the impulse to do justice to their gravity so that we can learn from it. These competing demands threaten to impose a moral standard that no artist—whether Depression-era or contemporary—could possibly satisfy.

When historical art shies away from graphically depicting the horrors of white supremacy or cultural imperialism, it can be accused of “sanitizing” or “romanticizing” the past. Yet when it does not, it can be accused of offending or disturbing viewers.

The way to deal with the conflicting demands of public memory is to create spaces in which members of the public can react to public historical works through the installation of response books or companion art works that explore the politics of history and the dynamics of race. As University of Kentucky English professor Frank X Walker, who is African-American, commented to the Washington Post, the mural could be placed within a broader context of the state’s and the nation’s history of slavery: “If it’s going to remain—and I think it should—then it should be part of a whole story,” Walker said.

Such public conversations are urgently needed on the campus of the University of Kentucky, as they are on all American campuses. Last month’s decision took place against a background of racial tension. In the words of Rashad Bigham, who was among the students who met with the President, the mural was mentioned among "a lot of different issues" concerning "diversity and inclusion" and "racial discrimination" at the university. In November 2014, the administration rejected on free speech grounds a Student Code of Conduct complaint brought by Bigham regarding a racist Instagram post. The following month, participants at die-in against police violence were reportedly pelted with coins dropped from upper floors of the library while anonymous racist commentary appeared on Yik Yak.

Sustained and substantive dialogue across the divides of racial misapprehension, anxiety, and pain will demand courage, imagination, dedication and perseverance. No shroud can cover that.