Artist Karyn Olivier installing her piece “Witness” on the domed ceiling in the atrium at Memorial Hall on August 15, 2018. (Photo: Mark Cornelison, UK)

The University of Kentucky (UK) has unveiled a new site-specific public artwork. The piece, by Philadelphia artist Karyn Olivier, was commissioned in response to a heated controversy around a fresco that students said was traumatizing. The fresco was first draped with a white cloth, then, after almost two years, was put back on view with contextualizing signage.

After lengthy internal discussion, UK commissioned the piece by Olivier to function in tandem with the mural, thereby creating a space where members of the community can reflect on the politics of history and the dynamics of race. In doing so, UK shows the way forward for other institutions navigating a similar terrain of conflicting needs and demands.

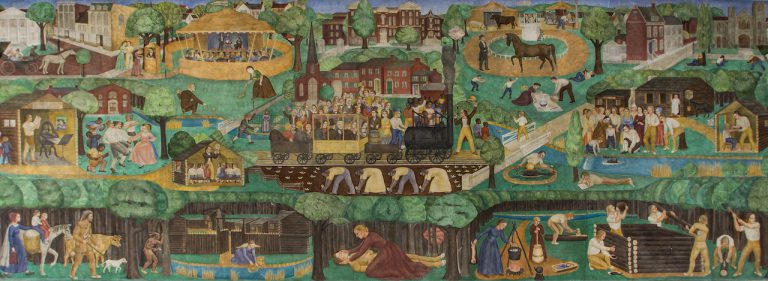

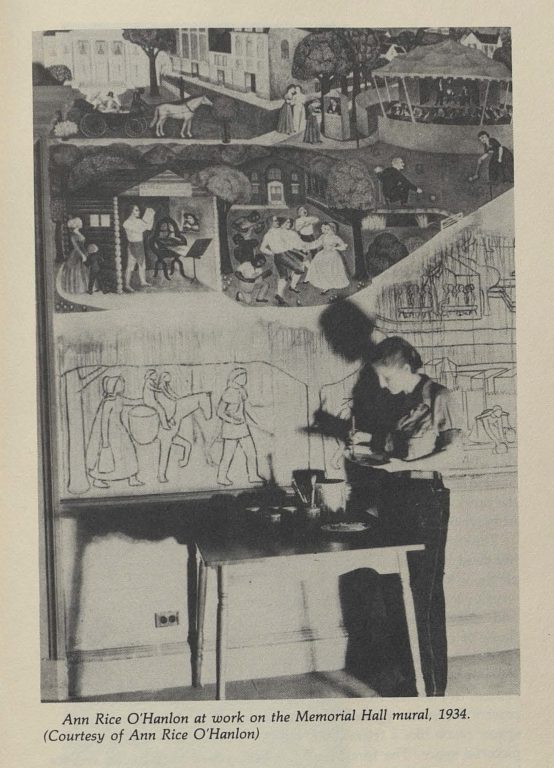

The fresco, which occupies a wall in UK’s Memorial Hall, was created by UK alumna Ann O’Hanlon for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) in 1934. It first sparked controversy in 2006 when the Student Government Association demanded its removal. The mural again came under fire in 2015 over its sanitized depictions of slavery.

Kentucky is not alone among universities and other cultural institutions that face outcries over historical artworks, monuments, or buildings that honor figures whose actions are now understood as problematic. When historical art shies away from depicting the history of white supremacy or cultural imperialism, it can be accused of sanitizing or romanticizing the past. And when art takes on depicting that brutality, it can be accused of offending or re-traumatizing viewers.

But artworks are never just about depicting official (or unofficial) histories. They are also conversations, platforms for discussion where we can reflect and air our understandings and misunderstandings of our collective history.

Fresco by Ann O’Hanlon, 1934. Aprox. 11 x 38 feet. Memorial Hall, University of Kentucky [click image for larger view]

A detail of UK fresco by Ann O’Hanlon showing black musicians and white dancers.

2015 Mural Controversy

Image from: Fowler, H. W. (1988). “Ann O’Hanlon’s Kentucky Mural.” The Kentucky Review, vol. 8 (no.1), pp. 57-68.

In late 2015, a group of students from the African American & Africana Studies department met with UK president Eli Capilouto to voice concerns about the experience of minorities on campus. The conversation touched on O’Hanlon’s 38-foot-long by 11-foot-high fresco, that fulfilled PWAP’s directive to document “the American Scene”. It is one of only 42 PWAP murals that exist.

One student in UK the meeting described how “each time he walks into class at Memorial Hall he looks at the black men and women toiling in tobacco fields and receives the terrible reminder that his ancestors were enslaved, subjugated by his fellow humans” and that “the mural provides a sanitized image of that history.”

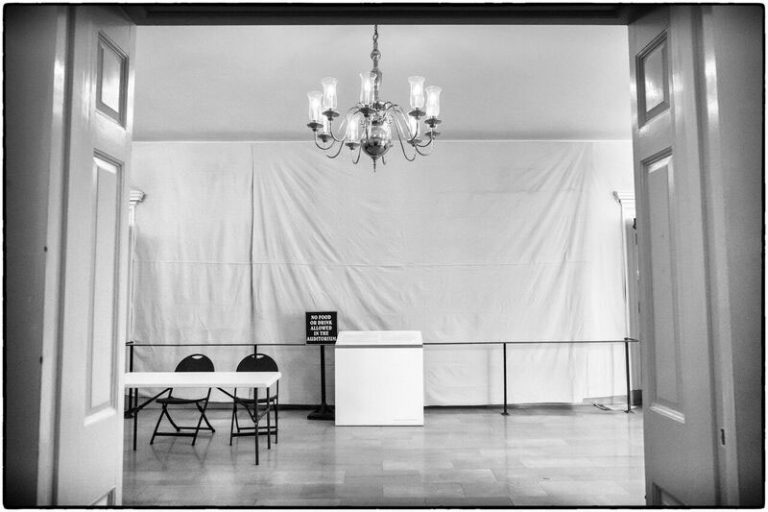

NCAC urged the university to preserve the mural and continue to display it with added information that would place it within a broader context of the state’s and the nation’s history of slavery. Since the mural is a fresco, relocation was not a possibility. As a temporary “solution” the administration chose to cover the work in white fabric.

In response to the covering of the mural, poet and essayist Wendell Berry, (a relative of O’Hanlon), wrote an op-ed accusing Capilouto of “overcooked political correctness.” In defense of O’Hanlon he posited that to depict slavery in a painting in 1934 had to have taken some courage.

Students of African American & Africana Studies sent an open letter to UK administrators suggesting that “the university could and should do more to improve the conditions on campus for all people of color” and that:

“…the closed-door nature of the discussions that have yielded the decision to cover the murals betrays the role of the university as a place for open dialogue and education. The opposing views held by the undersigned would have enriched the dialogue between the students and administration. It could have provided the university community with the space to learn about these murals, why some find them objectionable, and why some do not. Overall, a more open process would have been true to our mission. At day’s end, the skill we uniquely possess and at which we excel is our ability to educate. We owe it to our students and to ourselves to model civil discourse on matters on which we disagree and agree.”

Covered mural. Photo credit: Kopana Terry / University of Kentucky Research Guide.

After over a year of being shrouded, in April of 2017, the mural was uncovered, and signage was added to provide context around the work.

At the time, NCAC observed:

“President Capilouto’s statement exhibits an ironic tension between two impulses: the impulse to remove from view the wrongs of the past so as to protect a young generation of students from experiencing the pain of history, and the impulse to do justice to their gravity so that we can learn from it. These competing demands threaten to impose a moral standard that no artist—whether Depression-era or contemporary—could possibly satisfy.”

Olivier at work in Memorial Hall.

Conversation Through Public Art

For “Witness”, Olivier covered the domed ceiling of Memorial Hall in a layer of gold leaf, against which she adhered facsimiles of black and Native American figures depicted in O’Hanlon’s mural. Four large portraits of important but little-known Kentuckian historical figures of color are painted just below the chandelier that hangs from the dome’s pinnacle. They include Chief Red Bird, a Cherokee man who lived peacefully among white settlers until he was murdered; Georgia Davis Powers, the first African American to serve in the Kentucky Senate; Peter Durrett, a former slave who became a preacher and founded First African Baptist Church in Lexington; and Charlotte Dupuy, a slave woman who filed a freedom suit in 1829 against her master, Henry Clay.

A quotation from Frederick Douglass is displayed along the dome’s edge:

“There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven, that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.”

Olivier describes her work as addressing issues of race and inequity, and hopes it will help put the mural in a new context for future discussion. “The role of art is not to resolve things,” she said.

By commissioning this work, the University of Kentucky has created a model for other universities and cultural institutions that face outcries over problematic historical artworks. While other universities, as well as UK, have re-contextualized difficult historical works with signage or labels that explain their historical context, UK went further by commissioning Olivier to create a new work to keep the conversation going.