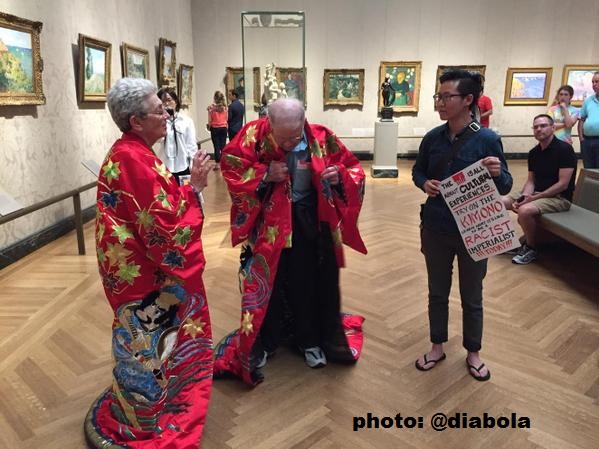

A small group of protesters descend on the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, declaring that a kimono exhibit was "Yellowface" cultural appropriation. A Smithsonian exhibition funded by Bill Cosby draws complaints from those who argue that the collection be removed in light of the accusations that the comedian has sexually assaulted dozens of women. And a protest at the Met in New York City sends its own peculiar message: "Renoir Sucks At Painting."

Are these events an indication that arts institutions are a ripe new target for activism and political agitation?

Perhaps. And maybe that's a good thing.

Of course, there are many in the art world who think otherwise. Protests are disruptive and potentially upsetting. In a recent article, “Why Art World Protests Against Renoir, Israel, Paul McCarthy or Anything Else Are Bad Politics," artnetNEWS editor-in-chief Benjamin Genocchio expresses that kind of concern. In what he calls a "provocative statement," he argues that much of this is "opportunism on the part of individuals using artists, artworks, and museums to bring attention to their causes. The subject of the protests may well be legitimate and real but the object is little more than a convenient springboard." He goes on to argue that he is "at odds on principle, and also as a matter of pragmatics, with protesting artwork and museums or cultural activity in general." He compares protest tactics to "online harassment," concluding with this: "Like arsonists, many of these people just love to see a blaze."

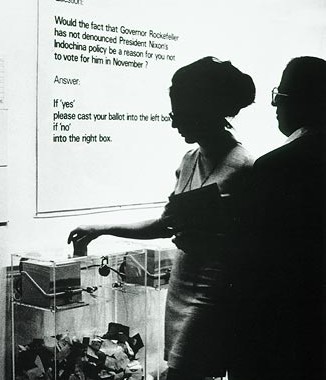

While charges of political opportunism are certainly legitimate, why shouldn’t a museum be used as a way to attract attention to social problems? Arts institutions are, after all, a type of ‘public square’. They are also often connected to the centers of power: Museums are supported by large government grants as well as by powerful individuals and corporations. They have the cultural power of determining what is valuable, high culture and what can be rejected as “not art” or not important art. All this makes museums the perfect place for public demonstrations on any number of issues (The image to the right shows Hans Haacke's 1970 MoMA exhibition, which posed questions about museum trustee Nelson Rockefeller.).

Genocchio asks:

Even if an artwork itself is the direct subject of the protest, what is the expected outcome of the protest? Removal? Censorship? The very laws which protect the right of artists and others to free expression enable protesters to take to the streets to denounce them. Paradox.

He raises an important point. At the Arts Advocacy Program, too often we encounter the removal or modification of an artwork/exhibit/event by museums in an attempt to placate protesters. But there is no paradox here; artists and protesters alike enjoy the right to express themselves. It is the responsibility of museums to stand firm and not remove or cancel artworks and exhibits. If their commitment to debate and artistic freedom was genuine, protests should not only be tolerated– they should be welcomed.

There is no need to shy away from a public that is simply voicing its opinions, however inconvenient their demonstrations may be. In fact, these protests might be seen as a sign of a healthy exchange of perspectives, and a reminder of the power of art to speak to different audiences.

The recent protests in art spaces are a challenge to the institutions that are targeted. Perhaps the demonstrations may interrupt the propriety and manners commonly associated with ‘high culture.' But so long as museums and protesters alike are committed to a free-flowing exchange, there is no reason to discourage activism.