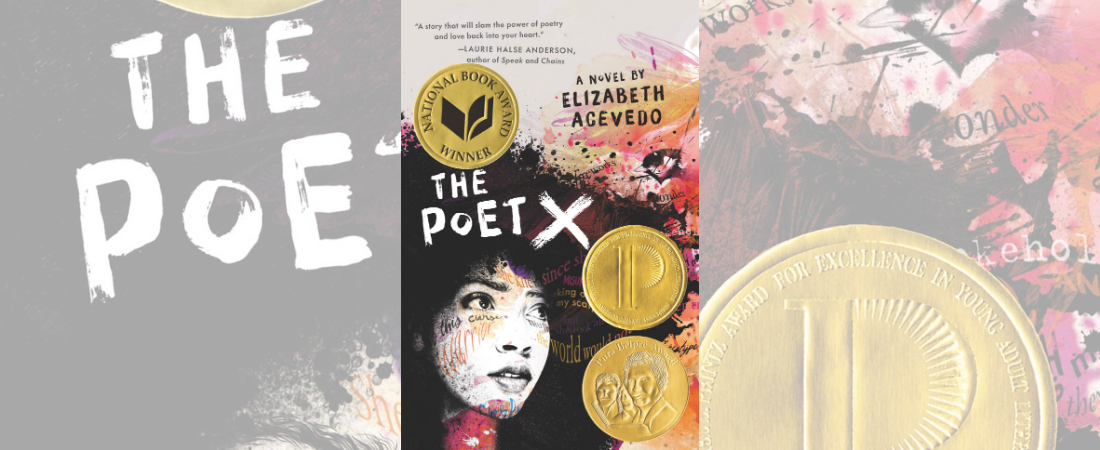

In the United States, no one has the right to dictate what other people think, say, or believe. That is particularly true in matters of faith. A recent lawsuit in North Carolina, however, demands that public schools protect one religious viewpoint above all others. Fortunately, the District Court rejected the plaintiffs’ argument that teaching The Poet X, an award-winning book by Dominican-American writer Elizabeth Acevedo, violated their right to freedom of religion. The court correctly found that public schools have a legitimate interest in having young people encounter challenging ideas–even ideas with which they disagree. The court also held that, in a country populated by people of diverse faiths–and no faith at all–a public school must not be forced to base its curriculum on anyone’s religious beliefs.

In their lawsuit, John and Robin Coble argued that The Poet X offends their religious beliefs due to its “promotion of an alternative path to liberation and meaning [in life].” They argued that, because this book offers an alternative to traditional Christian values, and because the protagonist questions her Christian faith, the book should not be allowed to be taught.

The book’s protagonist indeed struggles with the Christian faith in which she was raised. However, the Court observed that that struggle is a common theme in great works of literature, noting that “even figures in the Bible like Job doubted God’s goodness.” Other esteemed works that address that theme include James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain, and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Indeed, what would a biography of Martin Luther be, if not the story of a protagonist struggling with the faith in which he was raised?

Efforts to ban books that religious groups find offensive are certainly not new. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mel and Norma Gabler successfully campaigned against Texas textbooks which were inconsistent with their religious views. In the mid-2000s, Hindu organizations stymied the selection of history textbooks in California by claiming that they did not reflect certain extreme religious views held by some Hindus. The Harry Potter series has topped lists of challenged books for two decades due to complaints that the stories of witchcraft and wizardry are anti-Christian. Anti-Islamic groups have argued that any study about Islam, much less reading from the Quran, amounts to religious indoctrination. The Court recognized this history when it observed that “devising a curriculum that would satisfy the demands of all faiths in a religiously pluralistic society would surely be an impossible task.”

In addition, courts have affirmed that education is not indoctrination. In the words of the District Court, “the case law has made clear that the First Amendment does not tolerate, much less mandate, curricula that ‘cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.’” Hence, “[i]t would violate the Establishment Clause ‘to require that teaching and learning must be tailored to the principles or prohibitions of any religious sect or dogma.’”

According to Lake Norman Charter’s superintendent, approximately one in eight of the school’s students are of South Asian descent. The district is likely full of families who practice non-Christian religions or no religion at all and have their own beliefs and traditions, religious or otherwise, that seek to find “liberation and meaning.” Hence, the court properly rejected the Cobles’ attempt to limit all students to learning only about Christian views on some of life’s biggest questions.

The lawsuit also assumes that authors (and teachers) expect readers to agree with everything a book’s protagonist says or does. But that is not the case, and indeed it is for that very reason that “even the Bible may occupy a place in the classroom, provided education and exposure do not become advocacy or endorsement.”

In this case, the protagonist criticizes her parents’ religion. But in great literature, characters are nearly always morally flawed. Classics like Macbeth and Moby Dick include protagonists who do and say reprehensible things. Readers are obviously not meant to agree with all the characters’ choices, but to draw lessons from the characters’ struggles. Nor does every reader draw the same lesson. Some see The Catcher in the Rye’s Holden Caulfield as an inspiring rebel; others see him as a spoiled brat. Students deserve to approach The Poet X with the same critical lens.

Finally, the Court stated that the issue is not whether a specific book favors or criticizes religion. Because “objectivity in education need not inhere in each individual item studied; if that were the requirement, precious little would be left to read.” Rather, the Court ruled, “objectivity is to be assessed with reference to the manner in which often highly partisan, subjective material is presented, handled, and ‘integrated into the school curriculum,’” which includes looking at what other works are taught, since “surely [The Poet X] is not the only book to be read.” The Cobles, the Court held, had no evidence that the curriculum as a whole was biased against Christianity, nor that The Poet X was being taught in a biased manner. Hence, the Court refused to prohibit the teaching of the book pending the outcome of the litigation.

None of this implies that parents should be forced to have their own child to read books to which they strenuously object. Indeed, virtually every school district, including Lake Norman, allows parents to opt their child out of specific reading assignments and request alternatives. However, no parent should be allowed to dictate what every student should read. Particularly when some people commit violence in the name of religion, we need more tolerance for diverse ways of “finding liberation and meaning in life,” not less.

NCAC will continue to monitor this case.